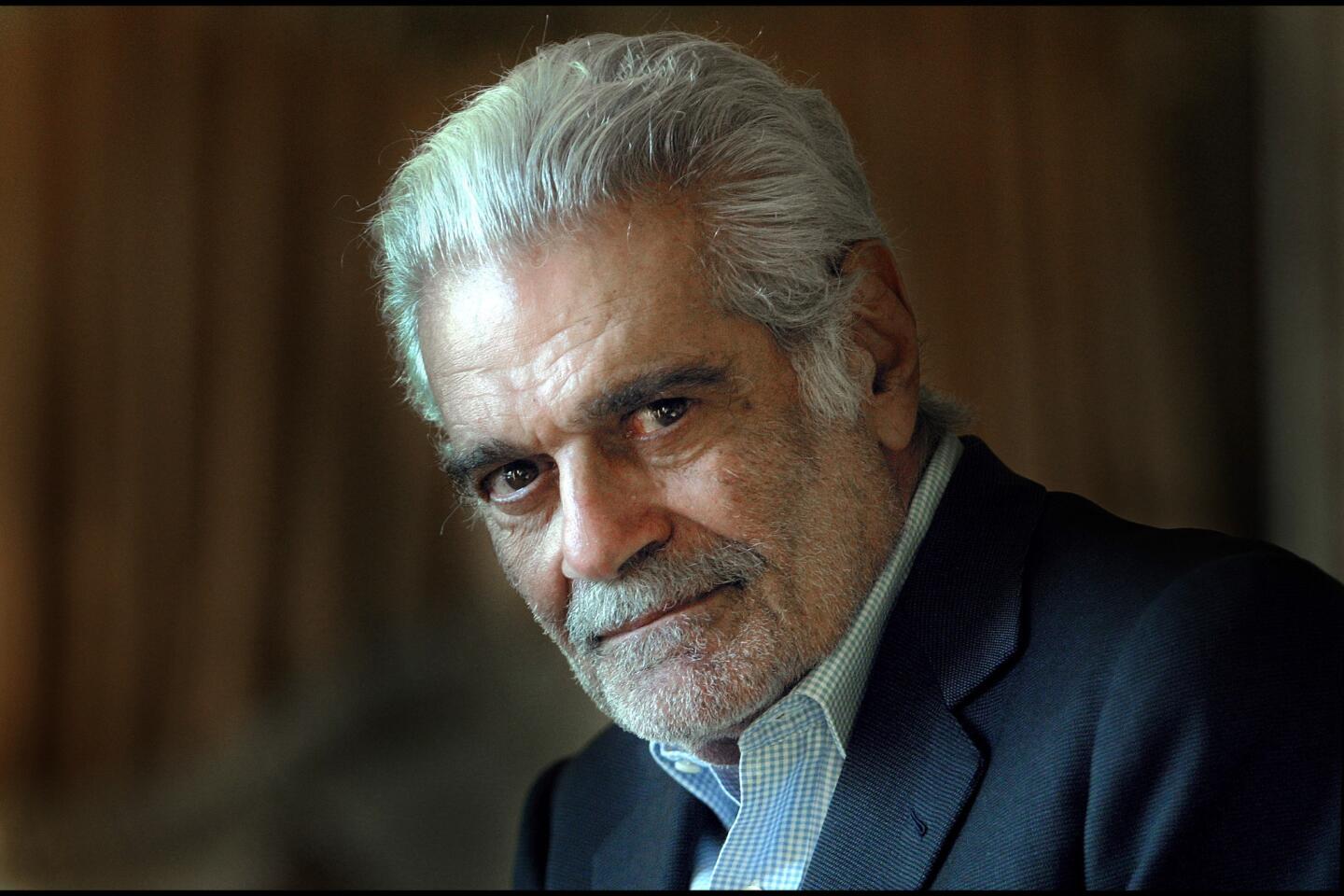

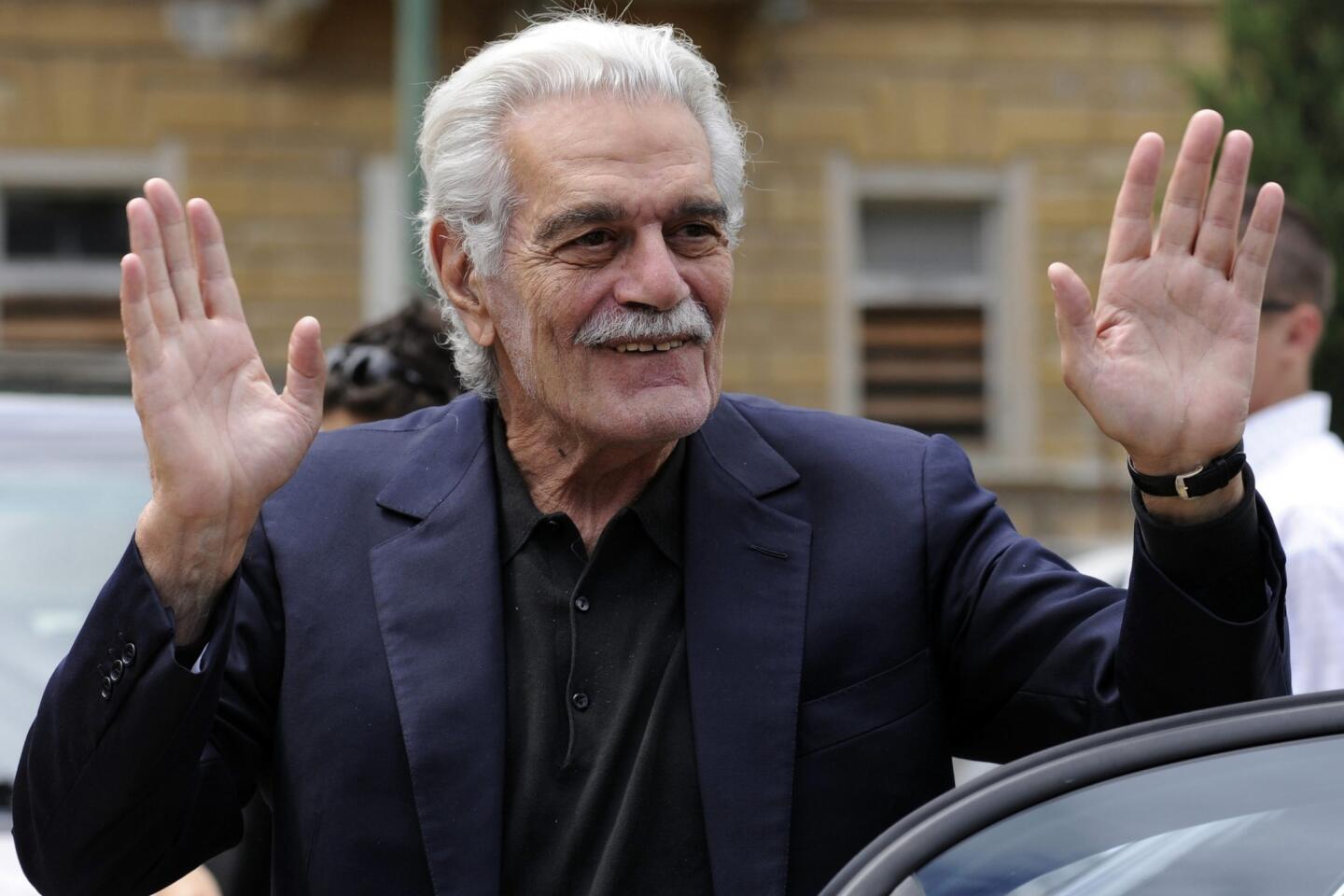

Omar Sharif dies at 83; heartthrob actor starred in ‘Doctor Zhivago’

- Share via

Omar Sharif, the Egyptian-born actor who rose to international stardom after emerging out of the distant desert in “Lawrence of Arabia,” died Friday, his agent said. He was 83.

Steve Kenis, Sharif’s longtime agent, told The Times that the actor died of a heart attack in a Cairo hospital. Sharif had been suffering from Alzheimer’s disease.

Sharif was already a box-office star in Egypt when director David Lean cast him opposite Peter O’Toole in the 1962 historical epic “Lawrence of Arabia,” which marked Sharif’s first English-speaking role.

The film introduced him as Sherif Ali, the tribal leader with whom British intelligence officer T.E. Lawrence helped the Arabs break up the Ottoman Empire, with a now-famous shot in which he slowly comes into view through a haze of heat while riding on the back of a camel.

“It’s arguably one of the great entrances in the history of film,” fellow actor Patrick Stewart told The Times on Friday.

Stewart, who said he did not know Sharif socially but followed him closely as an actor and contemporary, added, “There was a great deal of dignity about him and his work. And I don’t mean an uptight, formal, rigid dignity. There was a charisma, one that wasn’t to do with dazzle and razzmatazz, but with an intelligent presence, a thoughtfulness and an empathy.”

Sharif was “an actor’s actor,” said Jack Shaheen, an author who has written extensively about Arabs and Middle Easterners in cinema. “Not only was he the first Arab star in American cinema, but he played Russians, Jews, Hispanics. He was Che. He was Genghis Khan. He did it all. What I admired about him most of all was his willingness not to be typecast. He would play Arab villains or heroes, or any role. If he liked the role, he took it.”

Sharif said he landed his breakout role in “Lawrence” simply because he spoke English. “They looked at photographs of all the Egyptian actors, and David said if he speaks English, bring him here,” he recalled to The Times in 2012.

Sharif’s performance in the film earned him two Golden Globe awards and an Oscar nomination for supporting actor. He also forged an enduring friendship with O’Toole.

Three years later, Sharif played the title role in Lean’s adaptation of “Doctor Zhivago,” the Boris Pasternak novel about a sensitive Russian poet-doctor who finds himself torn between his wife and the love of his life against the backdrop of World War I and the Russian Revolution.

Sharif won another Golden Globe and reportedly received 3,000 proposals of marriage after the film debuted.

In 1968, Sharif played a memorable heartbreaker as Nicky Arnstein in the Barbra Streisand-starring “Funny Girl.” The film was banned in his native Egypt because he was cast as a Jew.

Although he made some 90 movies in his career, Sharif said those three remained his standouts.

“It’s true when people recognize me these days, those three films are the ones they talk about,” he told The Times in a 2003 interview. “But it doesn’t bother me. It’s better than having done none they remember. I find it endearing.”

Sharif conceded that he had gone through long down periods over the course of his career. “I went 25 years without making a good film,” he said, before thinking back and concluding it was more like 30 years.

Sharif could be as colorful a character off screen as he was on it. An avid card player, he taught himself to play bridge between takes on film sets and gradually improved to become one of the world’s best players. He co-wrote a bridge column in the Chicago Tribune as well as several books about the game.

For a time, gambling was a dangerous fascination for Sharif, and he was forced to sell his lavish bachelor pad in Paris in 1975 to pay gambling debts. “That’s why I was in so many trashy, idiotic films,” he told The Times in 2003. “I’d call my agent and tell him to accept any part, just to bail myself out.”

He made headlines again with a 2005 altercation outside a Beverly Hills steakhouse, during which he allegedly punched a parking valet for refusing to accept a 20-euro note as payment for retrieving his Porsche SUV.

Sharif, then in his 70s, pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor battery charge and was ordered to pay a $100 fine and attend anger-management classes, while being placed on two years’ probation. The valet also successfully sued Sharif for $318,190 in damages.

Sharif was born Michael Chalhoub in Alexandria, Egypt, on April 10, 1932.

His Syrian-Lebanese parents were wealthy and connected. His father was a timber merchant, and his mother played cards with Egypt’s King Farouk, a friend.

Raised as a Catholic, Sharif became a Muslim and changed his name at 21 when he married Faten Hamama, an actress known as Egypt’s movie queen, in 1955.

He said he chose Omar for Gen. Omar Bradley and Sharif because he thought it would be easy for Westerners to pronounce.

To O’Toole, however, Sharif would always be known simply as Fred, his nickname for his friend.

“How could he be called Omar Sharif?,” O’Toole said to The Times in 2001. “I came to see his airplane [land on location for ‘Lawrence of Arabia’] and here is this beautiful young man with black hair and the whiskers staring out of the window and they said he was Omar Sharif. I said, ‘That’s impossible.’”

In Sharif’s native city of Alexandria, word of his death drew proud recollections of his contribution to world culture from some -- and blank stares from some younger Egyptians.

“I am sorry, but I don’t know of this person,” 20-year-old engineering student Mohammed Safr told The Times.

But Ahmed Sarwar, an Alexandria physician in his late 60s, recalled a sense of national pride when Sharif vaulted to international fame. Before Sharif, he said, “no one had thought of Egypt in this way, as having something other than camels and the pyramids to offer the world.”

Staff writers Steven Zeitchik in New York, Lorraine Ali and Susan King in Los Angeles, and Laura King in Alexandria, Egypt, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.