Federal probe of L.A. County jail abuses notches its final guilty verdict

- Share via

A jury on Friday found that a former Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy lied to FBI agents about the beating of a visitor to a county jail.

The guilty verdict against Byron Dredd, which came nearly eight years after the 2011 assault, served as a capstone on the sweeping investigation federal authorities carried out into abuses in county jails. Dredd, who was being retried after an earlier mistrial, was the final defendant in a string of cases that arose from the probe.

Prosecutors won convictions or guilty pleas against each of the 22 deputies and higher-ranking officials who faced criminal charges — a group that includes former Sheriff Lee Baca and the department’s former second-in-command.

“All law enforcement officers will be held accountable for abusing their positions — whether that includes the illegal use of force or lying to cover up a civil rights violation,” said U.S. Atty. Nicola Hanna. “This former deputy actively tried to conceal the illegal actions of his fellow deputies, and today a jury held him accountable for his role in the cover-up of an unjustified beating.”

A jury in 2016 acquitted Dredd, 36, on charges he helped cover up the beating of the jail visitor, but deadlocked over whether he lied to investigators about the incident. Only two of the 12 jurors had wanted to convict Dredd of lying.

Prosecutors chose to retry him, and the case stalled as Dredd’s attorneys unsuccessfully appealed that decision.

In the retrial this week, Dredd’s attorney Nina Marino tried to sway jurors with the same argument she made in the first trial — that the deputy did not lie but had simply been mistaken in what he saw.

Unlike before, however, the jury did not struggle to reach a decision, returning a verdict after only an hour or so of deliberations.

“We are very disappointed in the verdict,” Marino said.

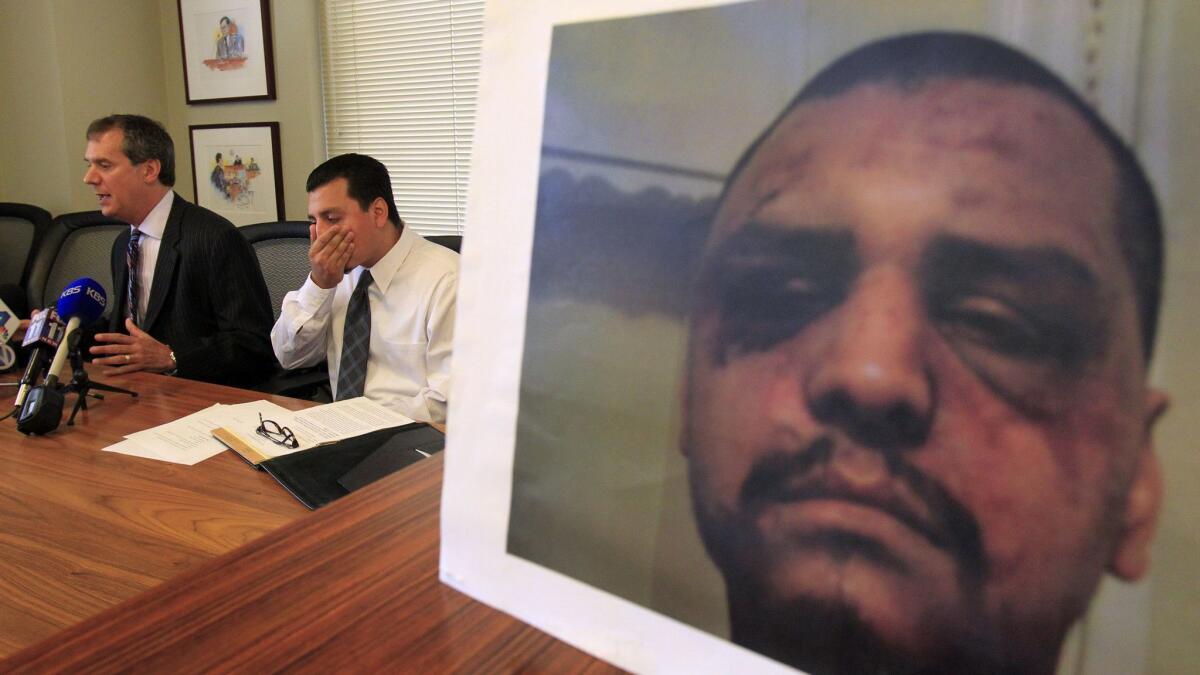

The accusations against Dredd stemmed from the February 2011 beating of Gabriel Carrillo, who had come to visit his brother, an inmate in the county’s main jail facility downtown.

Carrillo and his girlfriend were handcuffed and taken into custody after deputies said they found them carrying cellphones, which is against state law. When Carrillo reportedly mouthed off repeatedly to the deputies in a secluded room, he was punched, kicked and pepper-sprayed in the face.

After the beating, which left Carrillo bloody and bruised, the deputies and their supervisor claimed in reports that when they released one of Carrillo’s hands for fingerprinting, he attacked deputies and tried to escape. In an interview with FBI agents the next year, Dredd echoed that account, describing in detail how he had seen Carrillo attack the deputies.

Two of the deputies who participated in the beating eventually pleaded guilty and helped prosecutors convict three others who were involved by testifying that their story was bogus. The two deputies returned to testify at Dredd’s trial.

Dredd, who faces a maximum of five years in federal prison, is scheduled to be sentenced in May.

Mack Jenkins, who heads the Public Corruption and Civil Rights Section of the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles, said the verdict capped a “great accomplishment” by the prosecutors and FBI agents who took on the difficult task of investigating officers from another law enforcement agency, building cases against them and prevailing.

Jenkins credited his predecessor Brandon Fox, who orchestrated the jail prosecutions, and highlighted reforms the Sheriff’s Department has put in place in the aftermath of the scandal.

“These types of cases are hard — hard to uncover, harder to charge and exceedingly difficult to win,” Jenkins said. “But that’s our job. We want people to know we won’t sit by when there are allegations of corruption against public officials.”

Sheriff Alex Villanueva, who took over the department just last month, declined to fully stand behind the work his predecessor Jim McDonnell did to improve the jails.

Instead, he said in a statement that he would work on “continued reform” but planned to “assess the effectiveness of the checks and balances that have been put into place and see if any adjustments need to be made.”

“As a department, we have to move forward, learn from our past, and provide the best possible public safety protection for the residents of this county,” Villanueva said. “Working together, we will close this chapter in our department’s history.”

Times staff writer Maya Lau contributed to this report.

Twitter: @joelrubin

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.