Deputy gangs have survived decades of lawsuits and probes. Can the FBI stop them?

- Share via

For decades, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has been under pressure to break up tattooed gangs of deputies accused of misconduct.

But senior department officials, county leaders and prosecutors have failed to root out a subculture of inked clubs that pervades the nation’s largest sheriff’s agency.

Now, the FBI has opened an investigation of these secret societies that seeks to accomplish what high-powered sheriffs, blue-ribbon commissions and millions of dollars in lawsuits over the last 50 years have not: identify deputies who brand themselves with the matching tattoos and determine whether the groups they belong to encourage or commit criminal behavior.

The FBI probe into deputy gangs spotlights the shortcomings of local efforts, which have mostly been piecemeal, often resulting in investigations that focus on isolated acts of wrongdoing.

“I think it reveals that the various county agencies can’t or won’t conduct a thorough, credible, independent investigation,” said Sean Kennedy, a Loyola Law School professor and member of the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission.

“The Sheriff’s Department can’t investigate itself. The district attorney doesn’t seem interested in investigating the internal gangs. I would think being a member of an internal clique or gang raises serious questions about testifying deputies’ bias and credibility,” he said.

The Sheriff’s Department did not respond to that comment. On Friday, the department issued a statement from Sheriff Alex Villanueva saying he was unaware of any ongoing investigation by the FBI but would fully cooperate with such a probe.

Greg Risling, a spokesman for the district attorney’s office, declined to comment.

The FBI may have the means to discourage participation in the clandestine gangs that commonly sport ink featuring imagery of skulls and weapons, legal experts said. Each deputy’s design often includes a unique number denoting his place in the lineage of lawmen chosen as members. The groups are said to extract taxes, disguised as fundraisers for good causes, from other deputies.

“The feds are known for being pretty successful where others haven’t been,” said Laurie Levenson, a former federal prosecutor who teaches criminal law at Loyola Law School.

Levenson said wiretaps and undercover agents are effective tools that federal officials could use in a case like this one. Notably, federal grand juries could compel deputies to reveal their tattoos and talk about their actions in secret without allowing other deputies to tailor their testimony in order to cover for one another, she said.

Sheriff’s Department officials have said the 1st Amendment prevents them from ordering deputies to expose their ink, but those concerns would not apply if the tattoos are evidence of involvement in a group that engages in criminal activity, Levenson said.

She added that a federal investigation could also end up demonstrating — as many deputies have argued — that there is no criminal element to the inked groups.

“At the end of all this, a grand jury may have absolutely nothing to say,” Levenson said. “Having a bunch of tattooed deputies marching in there who have not committed crimes could be the best thing that ever happened to these officers.”

The Times reported Thursday that FBI agents have been asking deputies about the inner workings of the Banditos, a club of deputies at the Sheriff’s Department’s East L.A. station who brand themselves with matching tattoos of a skeleton with a sombrero, bandolier and pistol, according to three people with close knowledge of the matter.

The agents have been trying to decipher whether leaders of the Banditos require or encourage prospects to commit illegal acts — planting evidence, engaging in unlawful shootings — to gain membership in the group, said the sources, who spoke to The Times on the condition of anonymity because the investigation is ongoing.

The FBI agents have also been asking about similar behavior by other groups like the Spartans and Regulators at the department’s Century station, and the Reapers, who operate out of a station in South Los Angeles, the sources said.

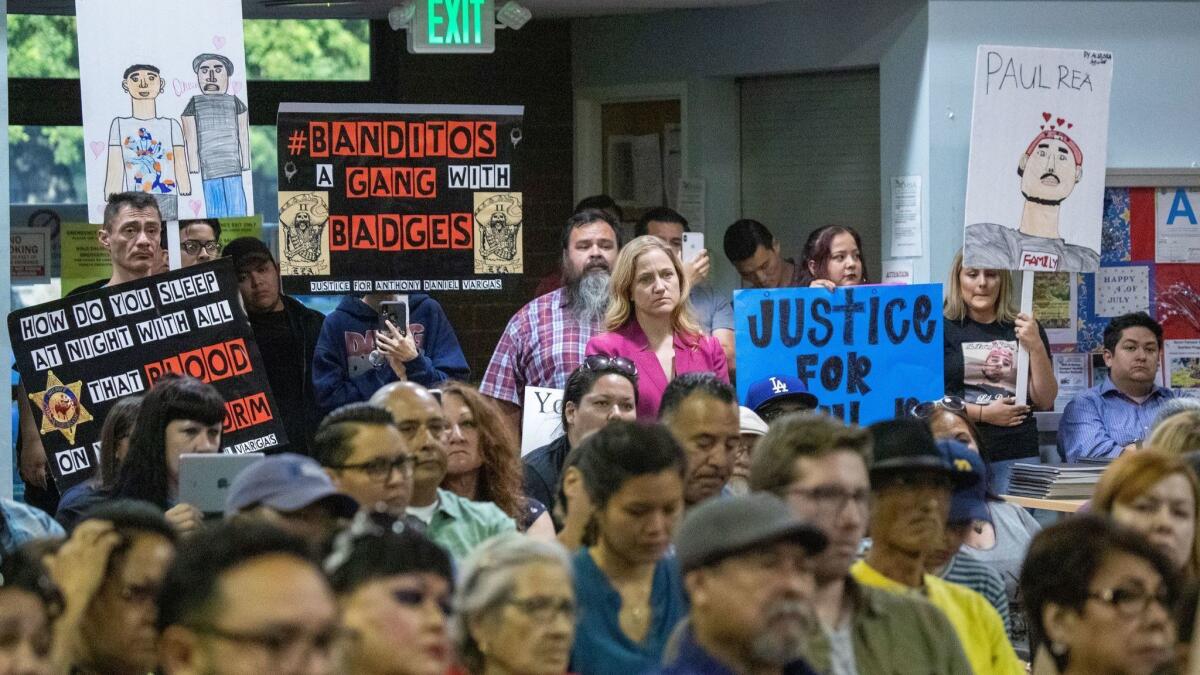

The probe follows allegations of harassment and beatings by members of the Banditos at an off-duty party last fall. The revelations have stoked public outrage about the groups, most recently at town hall meetings last week that were focused on issues at the East L.A. station.

“We have a cancer that is infiltrating the Sheriff’s Department. That cancer is the gangs…. The gangs are coddled and encouraged by the sheriff,” Gil Botello, an East L.A.-born resident, told the oversight commission at a public meeting Thursday. “Enough with the stories. Enough with the dialoguing. We need you to take action.”

Officials and community members have long expressed concerns over secret societies of inked deputies that date as far back as the 1970s with the Little Devils at the East L.A. station. Other groups such as the Pirates, Jump Out Boys and Cavemen have surfaced over the years, with the cliques so enmeshed in department culture that their existence does not strike many deputies as odd.

When news emerged in 1990 that a group of Lynwood station deputies known as the Vikings were engaging in street gang behavior, flashing hand signs and addressing one another as “homeboy” or “OG” for “original gangster,” then-Sheriff Sherman Block launched a department inquiry into possible wrongdoing by the group, which sported tattoos of a blond Viking head.

The revelations came after 81 residents in the mostly black and Latino area filed a federal class-action lawsuit accusing members of the station of racism, brutality and trashing their homes. A federal judge in the case concluded in 1991 that the Vikings were a “neo-Nazi, white supremacist gang” that operated under leaders who “tacitly authorize deputies’ unconstitutional behavior.”

Though he pledged an investigation of improper conduct, Block made light of the allegations of gangster behavior, saying that “gangs get a kick out of the fact that deputies have their own sign.” He added that the brotherhoods “could be a very positive thing” and a “badge of honor,” according to contemporaneous news reports.

Block’s treatment of misconduct as an issue that’s separate from the wider gang subculture in the department is one that subsequent sheriffs would repeat. Some critics say sheriffs have sent mixed messages about the groups.

Former Sheriff Lee Baca repeatedly denounced the inked clubs even as his undersheriff, Paul Tanaka, was publicly known to have a Vikings tattoo for years during his service as one of the department’s top commanders. Tanaka is now in prison for conspiracy and obstructing an FBI investigation into deputy jail abuse, a scheme for which Baca was also convicted.

Former Sheriff Jim McDonnell abolished several logos used in the department that he deemed offensive, including an insignia that refers to the East L.A. station as “Fort Apache.” He announced a “comprehensive study” of deputy cliques but took pains to say that it was not a formal investigation and that he was mindful of deputies’ 1st Amendment rights in having the tattoos.

Shortly after taking office, Villanueva brought back the banned East L.A. station logo, which also features an image of a boot with a riot helmet, the words “Low Profile,” and a Spanish phrase that means “Always a kick in the pants.” Critics say the symbol casts the station as a Wild West outpost of deputies who crack down on locals. The logo arose out of confrontations between law enforcement and anti-Vietnam War protesters during the 1970 Chicano Moratorium rally, according to KPCC/LAist.

Villanueva, who served at the East L.A. station for seven years as a young patrol deputy, has defended the logo as a source of pride that has nothing to do with the Banditos. He recently implemented a policy that specifically bars department members from participating in any groups that promote conduct that violates people’s rights, and in June, his office presented a criminal case against four alleged Banditos to the district attorney.

Still, Villanueva has said there’s nothing wrong with the existence of the Banditos or other inked deputy clubs as long as members don’t commit misconduct. He’s downplayed much of the conduct of the groups as “intergenerational hazing.”

Villanueva’s undersheriff, Timothy Murakami, said at a public meeting in March that the department was not looking into the Banditos or other exclusive groups as a “systemic issue.”

“Right now we’re just looking at the actions of individual subjects, not the group as a whole,” he said, adding that an investigation could be broadened if warranted.

Blue-ribbon panels have issued scathing critiques of internal deputy gangs to limited effect.

The Kolts Commission, created in response to uproar over excessive force by deputies, conducted a sweeping inquiry into the Sheriff’s Department and recommended in 1992 that officials investigate and punish deputies who act like gang members. The agency dismissed the advice.

“The department is confident there are no racist deputy gangs or cliques within the organization and therefore disagrees that an internal investigation is appropriate,” said then-Sheriff Block.

In response to recommendations by the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence in 2012, the department began training new deputies about destructive cliques and rotating jail assignments more regularly in order to prevent clubs from forming.

Evidence of groups of deputies with coordinated skull tattoos have nonetheless resurfaced at stations including Compton and Palmdale.

Defenders of the clubs say they boost morale and are formed by deputies who go beyond what’s expected of them by staying late and showing bravery and an eagerness to go after criminals.

Det. Ron Hernandez, president of the Assn. for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs, has said that he has a tattoo associated with the now-shuttered Firestone station and that it signified a fellowship of hard workers, not a rogue clique.

“I think the department should focus more on the value of a deputy’s work product,” he told The Times last year.

Michael Gennaco, who monitored the Sheriff’s Department for more than a decade as head of the Office of Independent Review, which is no longer in operation, said it has been extremely difficult to simply get rid of the internal gangs.

He said officials have struggled to hit the right balance between protecting individual deputies’ rights to freedom of expression and association while stopping the groups from becoming vehicles for improper or illegal behavior.

Some deputies fired for misconduct tied to internal gangs have sued and gotten their jobs back, Gennaco noted.

Actions by deputies who are members of the clandestine groups have cost county taxpayers millions in lawsuits over the last several decades. In justifying the settlements, the county’s lawyers often cite specific behavior by deputies without any acknowledgment of their alleged gang affiliation.

County supervisors have asked for an official tally of each case against the county involving allegations of secret deputy cliques since 1990 and the amounts the county had to pay out in each case.

Miriam Krinsky, a former federal prosecutor who served as executive director of the Citizens’ Commission on Jail Violence, said news of the FBI investigation is a reminder of the “‘Groundhog Day’-like phenomenon” in addressing inked deputy groups.

“The decades of reports sitting on bookshelves should be enough to convince people that there is a problem here,” she said. “And certainly the millions of dollars paid in lawsuit settlements should reinforce the recognition that there is a problem.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.