After mass shooting, San Bernardino endures a surge in deadly violence: 150 shootings, 47 slayings

San Bernardino has seen a surge in violence this year, with more than 150 shootings so far.

- Share via

The sound of gunfire and sirens drew about a dozen people out of their homes on San Bernardino’s west side one recent Wednesday night.

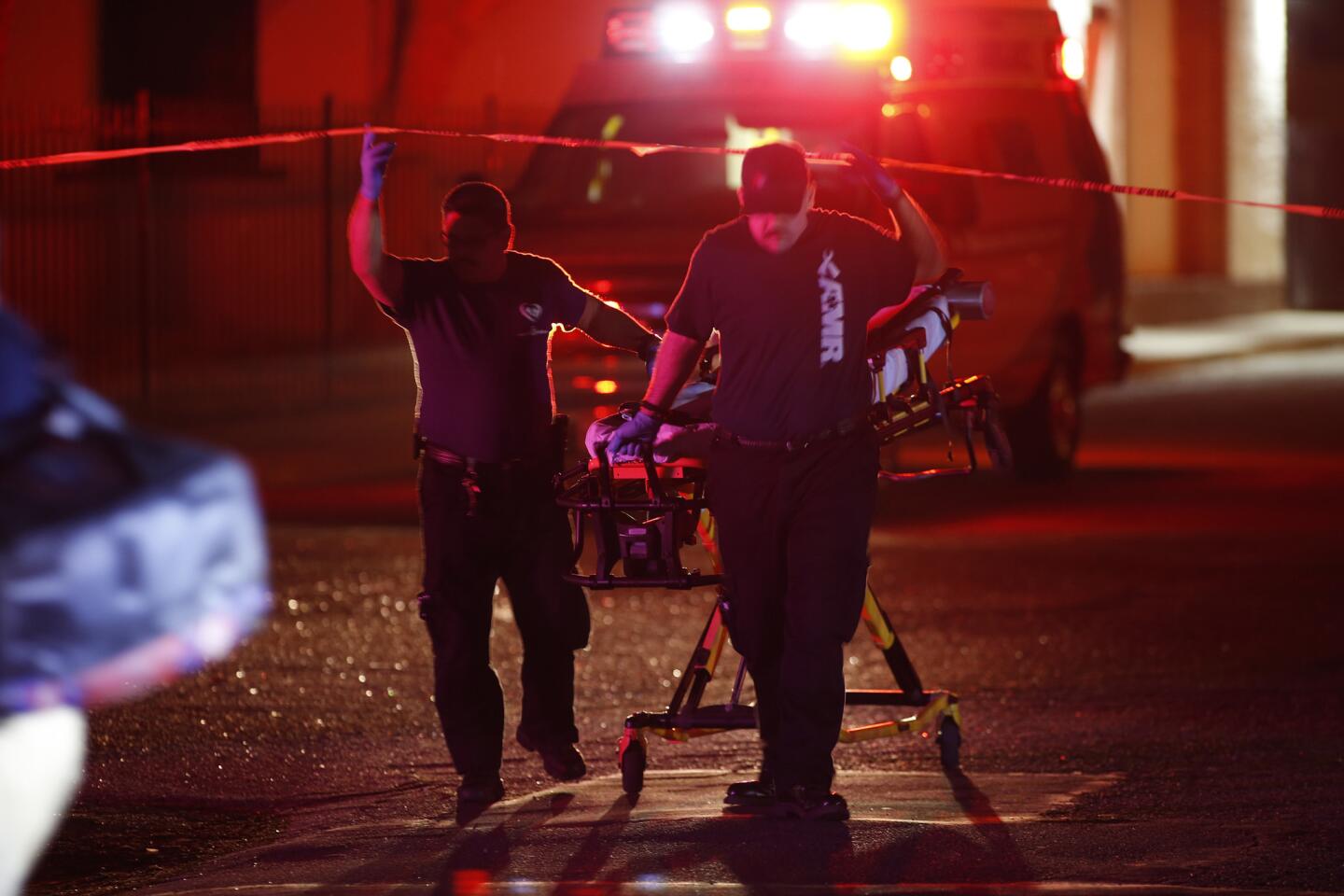

A beat-up Honda sat in the street — a small cross dangling from the rearview mirror, two bullet holes in the door. Rescue workers pulled Alejandro Herrera, 28, from the driver’s seat and wheeled him into an ambulance.

“The other day, they killed someone down the street,” said a middle-aged woman, leaning against a fence next to her husband. All around this part of the city, she said, there are candlelight memorials to victims of violence.

“Before, we would hear about killings every once in a while. Now, there are so many,” she said, asking that her name not be published for fear of becoming a victim herself.

A few days later, in a neighborhood less than two miles away, investigators pulled the body of Jose De La Torre, 24, from the trunk of a Nissan.

The next night, Shonta Edwards, 33, was shot to death outside an apartment complex about half a mile from there.

And soon enough, Herrera, who died at the hospital, had his own candlelight memorial on the sidewalk in the neighborhood where he was shot.

::

San Bernardino, still healing from the Dec. 2 terror attack, has seen a surge in violence this year unlike any it has faced in decades. With four months left in 2016, there have been 150 shootings and 47 slayings in the city of 216,000 residents. It had 44 homicides all of last year, including the 14 people killed by terrorists at the Inland Regional Center.

The city is now on track to have more murders than in any year since 1995, when 67 people were killed, and there is no clear explanation why.

Residents and officials point to a police force hobbled by budget cuts and attrition. But the budget situation was bad last year too, and the homicide rate was far lower.

San Bernardino has had about as many homicides as Oakland, which has nearly twice the population. San Jose, almost five times more populous than San Bernardino, has had 35 killings.

If the current pace continues, San Bernardino will end the year with a homicide rate of about 31 per 100,000 residents. Chicago’s rate last year was about 18; Los Angeles had seven.

In addition to the 47 homicides, three people have been killed by police.

“Our city right now is bad,” said resident Aguadia Brown, 27, whose cousin, a friend and his son all were killed this year. “It’s like everyone is on edge, and nobody really knows how we’re going to fix this.”

The killings have disproportionately victimized the city’s black residents, who account for 14% of the population but nearly half of those killed. Certain neighborhoods have been affected, but the mayhem has occurred throughout the city.

Police Chief Jarrod Burguan says the city has been especially hard hit by state initiatives that reduced some drug and property-related felonies to misdemeanors, leading to shorter sentences for criminals.

Others say the city’s dearth of economic opportunities, its years of cuts to diversion programs and a lack of other basic services — such as working street lights in many neighborhoods — have contributed to this year’s violence.

Because of San Bernardino’s financial turmoil, which began even before it declared bankruptcy in 2012, the size of the Police Department has been reduced repeatedly over the years.

The ranks have gotten so thin that officers who specialize in drugs, gangs and traffic enforcement have been reassigned to patrol just to keep up with calls for service.

“We’re not getting to calls fast enough,” Burguan said. “We don’t have the capacity to investigate everything that’s reported in the city.”

The Dec. 2 attack turned the world’s eyes toward San Bernardino. And the presidential election has made it an ongoing political talking point.

But even as its name has come to symbolize the dangers Americans face at the hands of terrorists, the city is suffering a mounting nightly toll with little attention from the outside.

::

On a Friday night in June, Det. Ernest Luna and Officer Brian Olvera drove through town in a patrol car, a rifle mounted between them.

They had been pulled off their regular gang detail to patrol the streets for a 45-day operation aimed at calming the surge of violence. The city also paid four county deputies to beef up its numbers during that period.

As they wound their way through San Bernardino, Luna said officers who won widespread support after the terrorist attack at the Inland Regional Center now struggle to get information from residents that might help solve or prevent violence.

“During IRC, it seemed like everyone loved us,” Luna said. “But it’s kind of gone back to how it was.

“A lot of times, they’re scared,” he added. “They have to live in the neighborhood.”

Fewer than 40% of this year’s homicides have been solved.

In one neighborhood, Luna and Olvera drove past a corner where a long-established gang had painted two tall, elaborate murals of the Virgin of Guadalupe and the Aztec calendar — each emblazoned with the gang’s name in massive letters.

The brazen graffiti on the walls of two neighborhood stores is a vivid reminder of the city’s dwindling resources.

In 2008, there were more than 340 police officers on the force. Today, there are about 215.

The gang unit used to be twice its size, Luna said.

The department has fewer officers per capita than nearby Riverside and Ontario, neither of which have comparable problems with violence.

Burguan said he needs about 300 officers to comfortably meet the city’s basic service needs — more, he said, if city officials expect to blunt violence through sheer police presence.

The city is trying to make do as it prepares to emerge from bankruptcy later this year.

The Police Department is trying to fill about 30 vacancies and is hoping for a federal grant to add 11 officers. But the hiring process is slow.

In the meantime, officers are busy.

Before their shift was over, Luna and Olvera stopped to talk with the mother of four young gang members about one of her son’s Facebook posts and responded to a man exposing himself at a convenience store.

They stopped a group of young men drinking beers outside an east-side neighborhood and entered their names on gang identification cards. They helped search for and arrested a teenager who they heard had pulled a gun on people in an apartment complex.

And nearby, officers responded to a stabbing that — two weeks later, when the victim died — would become another homicide.

::

Two days before Herrera was killed, a few dozen clergy members, residents and activists gathered to call for an end to the violence.

They began in front of St. Bernardine Church, the city’s oldest Catholic parish, and walked two-by-two to City Hall, about a half-mile away, shouting, “Alive and free is what we want to be.”

When they reached the steps of City Hall, a woman read aloud the names of San Bernardino’s homicide victims.

“John Black.”

“We remember you,” the crowd replied.

“Rayshawn Sandy.”

“We remember you.”

The march and recitation of names are a monthly ritual organized by Inland Congregations United for Change, a coalition of local religious groups and others that has been pushing the city to do more to stop the killings.

Organizer Sergio Luna, a father of two young children who has lived in San Bernardino for 17 years, says the violence weighs on the entire community.

“Knowing there’s a few shootings within a few blocks from your house,” he said, “that brings a psychological toll.”

While the death toll is particularly high this year, Luna said that for years, San Bernardino has had a high homicide rate that went largely ignored.

After the terror attack, he said, “all of a sudden, everyone cared about mass shootings in San Bernardino. But we’ve been crying about urban gun violence for many years.”

Since 2014, when there were 43 homicides — about one every eight days — the group has been pushing the city to adopt Operation Ceasefire, a program used in cities around the nation to reduce homicides by reaching out preemptively to those at risk of violence.

“We cannot only prioritize first responders after violence takes place if we’re not prioritizing preventing violence from taking place in the first place,” Luna said.

Burguan, the police chief, said that earlier this year, the city was turned down for a state grant to help fund Operation Ceasefire.

The decision made Burguan wonder whether the city is alone in its battle against killings, he said.

“Who really is that concerned about San Bernardino? Or are people at the state level happy letting San Bernardino drown in this stuff?” he said. “We clearly have the most significant crime spike of any place in the state, and all that money went elsewhere.”

City Manager Mark Scott said San Bernardino is looking for other private or government grants to fund Operation Ceasefire, which he estimates would cost about $500,000. The city agreed to spend $175,000 on it.

::

On a hot evening in July, a man waiting outside a liquor store on the east side shot 9-year-old Travon Williams, his father and another man. The boy had spent the afternoon swimming with his dad.

Travon’s family didn’t have the money to pay for his burial.

So in a ritual that has been enacted after many of the city’s homicides, Travon’s family and friends, and those of his father, spent hours in restaurant parking lots, washing cars and soliciting donations from passing drivers.

On a 104-degree day, they hosted a park barbecue that from afar might have been mistaken for a birthday party. They sold snow cones and popcorn and T-shirts with a photo of Travon and his father, superimposed with angel wings.

It was more than just a fundraiser, family members said. It was a call to the community to gather, to draw some attention to the onslaught of violence that had now claimed the life of a fourth-grader.

“It’s not even just because of my nephew, but because of all the killings that happened before him and all the ones that have happened after,” said Travon’s aunt, Erica Newman. “We’re trying to stop all this killing.”

When the day of the funeral came, hundreds of mourners filled the Way World Outreach, a large church not far from Cal State San Bernardino.

Father-and-son caskets were covered with red, white and blue flowers. Travon’s younger sisters wore red, white and blue barrettes.

Toward the end of the service, mourners began a procession past the caskets. Many were in their 20s and held small children by the hand or babies in their arms. They visibly struggled to walk past the slain 9-year-old boy.

The pastor walked to the front of the room and leaned into a microphone.

“This is not normal,” he said emphatically. “It’s not normal to see mothers cry, aunties cry, because their children are killed.

“This is enough, Lord, of young people losing their lives. This is enough. This is enough.”

Twitter: @palomaesquivel

MORE LOCAL NEWS

Dr. Bob Sears, critic of vaccine laws, could lose license after exempting toddler

California’s voter guide comes with 224 pages and a $15-million price tag

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.