This L.A. sheriff’s deputy was a pariah in federal court. But his secrets were safe with the state

- Share via

For years, James Peterson’s secrets were safe in the courtrooms of Los Angeles.

The L.A. County sheriff’s deputy, who trawled a stretch of the 5 Freeway for drug traffickers, often testified in the state court system about his arrests. No one knew to ask about his troubled past.

Then one of Peterson’s cases landed in federal court.

Prosecutors in the U.S. attorney’s office delved into the deputy’s personnel records for black marks that could call his credibility into question. They found records alleging dishonesty and other misconduct, and they turned the information over to attorneys defending two accused drug traffickers, according to court documents reviewed by The Times.

The case — along with several others built on Peterson’s work — collapsed, and the deputy became a pariah in federal court.

The different treatment of Peterson’s past in state and federal courts wasn’t happenstance. It was just one example of how special privacy protections granted to California’s police officers prevent defendants, prosecutors and jurors from learning about information that could undermine an officer’s credibility. Those special privacy protections don’t apply in federal court.

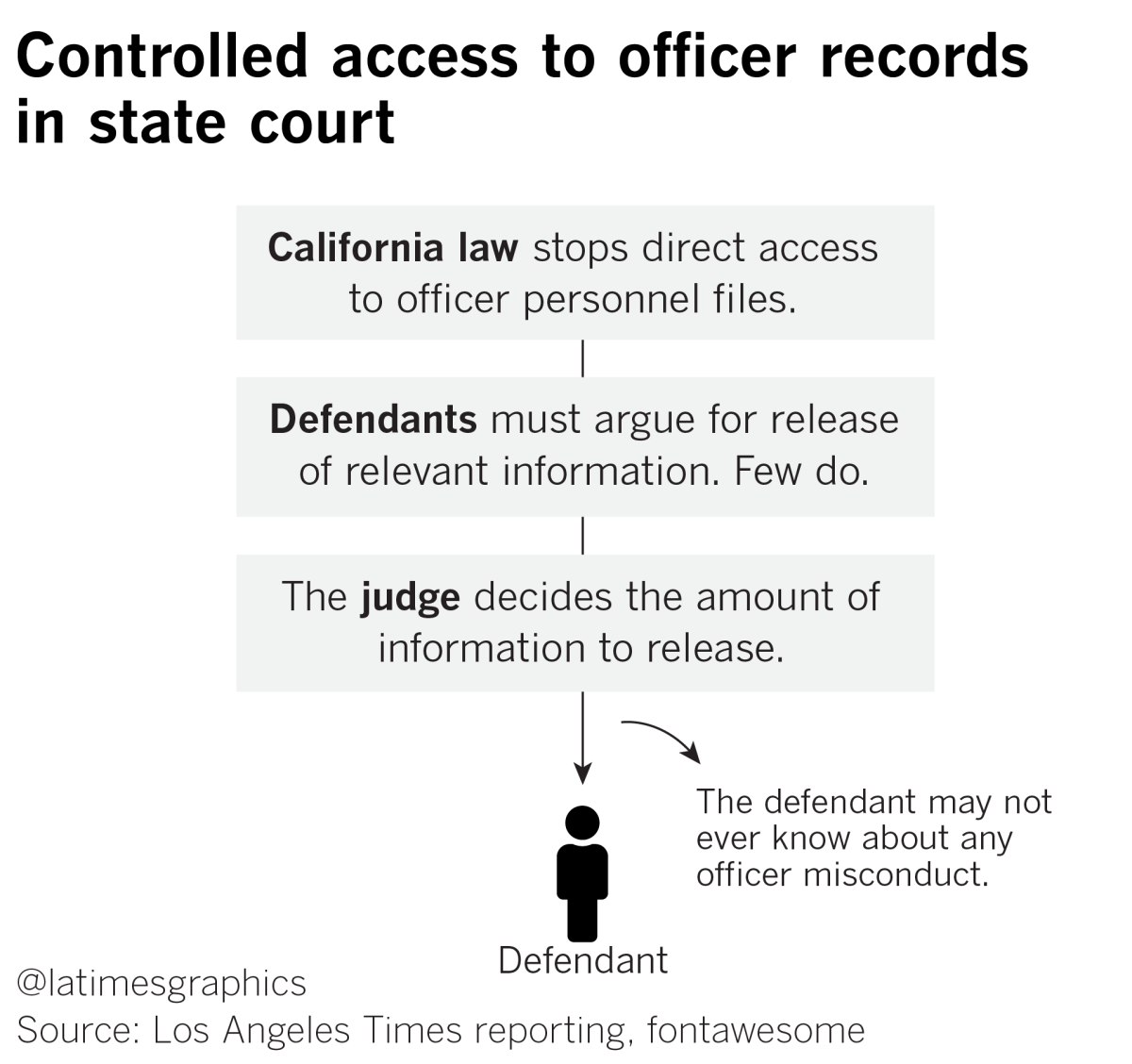

California is the only state in the nation that blocks prosecutors from directly accessing the personnel files of law enforcement witnesses. Defendants who want to find out about an officer’s past must navigate a Byzantine legal process that limits disclosures about previous wrongdoing or blocks the release of information altogether.

A Times review of recent state court cases in which Peterson was a potential witness found that only two of 170 defendants facing felony charges tried to obtain information about past complaints against him — and, even in those cases, the defense came away with little to show for it. Most of the others accepted plea deals offered by prosecutors before Peterson was called to testify.

The findings, defense attorneys and some legal experts say, highlight how California’s laws risk denying defendants fair trials by preventing them from learning about evidence that could lead judges and jurors to doubt an officer’s truthfulness.

A Times investigation

Aug. 9, 2018

An L.A. County deputy faked evidence. Here's how his misconduct was kept secret in court for years.

Aug. 9, 2018

You've been arrested by a dishonest cop. Can you win in a system set up to protect officers?

Aug. 14, 2018

One cop came forward to expose secrets in his own ranks. The revelation rocked the court system.

Aug. 15, 2018

Here's how California became the most secretive state on police misconduct

“The stakes are far too high to play a shell game with this kind of material,” said Jonathan Abel, who studied law enforcement privacy laws across the country as a fellow at the Stanford Constitutional Law Center. “Innocent people will serve time in prison … because police misconduct evidence is not disclosed.”

But Gregory Palmer, an attorney who advises police departments across the state, defended the privacy laws, arguing that they do allow defendants to learn about a law enforcement witness’ past if there is legitimate reason. Without the laws, he said, defense attorneys would be able to malign a police witness regardless of whether it was relevant to their case.

“As long as California recognizes a police officer’s right to privacy, we have to have a way to balance that right against a defendant’s right to a fair trial,” said Palmer, who specializes in instructing law enforcement agencies on how to oppose legal attempts to open an officer’s disciplinary file. “California’s law does that.”

A Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department spokeswoman said she could not discuss Peterson’s disciplinary history, citing state law. The deputy also declined to comment.

California lawmakers this month are weighing a proposal that would allow the public to see some law enforcement misconduct records. Disclosure of internal discipline would mark a dramatic change.

The state’s confidentiality laws are so strict that an appellate court ruled last year that L.A. County Sheriff Jim McDonnell could not give prosecutors the names of about 300 deputies disciplined for dishonesty, tampering with evidence or similar misconduct.

The Times identified dozens of deputies on a 2014 version of the Sheriff’s Department’s list of problem officers. Among them was a deputy convicted of filing a false report and another suspended after he pulled over a stranger and received oral sex from her in his patrol car. Both kept their jobs.

The California Supreme Court has agreed to consider McDonnell’s appeal in the case. But even a decision in the sheriff’s favor would not come close to matching the disclosure rules in federal court.

There, prosecutors are required to give the defense any material from officer personnel files that “reflects upon the truthfulness or possible bias” of potential witnesses, according to Department of Justice policy. And if they are unsure whether something should be handed over, the policy instructs prosecutors to “err on the side of disclosure.”

The rules are designed to ensure federal prosecutors meet their so-called Brady obligations, named after the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1963 decision in Brady vs. Maryland. In it, the justices ruled that the Constitution requires prosecutors to tell defendants about evidence that might be favorable to them. In later cases, the high court expanded the obligation to include information about government witnesses that calls into question their credibility.

But under California’s Pitchess laws, named after a former L.A. County sheriff who fought to keep police disciplinary records sealed, local prosecutors are barred from looking at that information. Instead, the burden falls on defendants to persuade judges to examine officers’ files.

To do so, they must make a specific allegation that a police officer lied about an arrest, used excessive force or committed some other serious breach. The judge then looks at the officer’s records in private for complaints about similar conduct and determines whether it should be disclosed to the defense.

The law does not allow complaints of misconduct more than five years old to be disclosed. If a judge decides something should be turned over, typically only basic information is released, such as the names and contact information of people who previously accused the officer.

In a San Fernando courtroom last year, a state court judge, David Walgren, went through Peterson’s file at the request of a defense lawyer.

Peterson had pulled over Ramon Mercado and his father in November 2016 and discovered a gun and some drug residue inside a hidden compartment in the trunk of the car. In his arrest report, Peterson wrote that Mercado had said the car belonged to him and gave Peterson permission to search it.

Mercado, however, insisted he was innocent, telling his attorney that he had borrowed the car from a friend and had known nothing about the hidden compartment and gun. Mercado wrote in a sworn statement to the judge that he never told Peterson he owned the vehicle.

The car’s owner corroborated the story, telling an investigator that he lent the vehicle to Mercado and did not mention the secret compartment, defense attorney Jeffrey Vallens said.

Later, Vallens received a tip from a prosecutor in the case that there might be something incriminating in Peterson’s past. Vallens asked the judge to review Peterson’s file, arguing that if the deputy had lied about Mercado, he may have been caught lying about other things.

Judge Walgren limited his search to episodes of dishonesty and did not consider any incident more than five years old, court records show. Vallens said he received only the name and phone number of a prosecutor in the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles. The judge ordered him not to disclose the name to anyone else.

Vallens then had to figure out what the prosecutor knew about Peterson.

He called the federal prosecutor and left a message. A different prosecutor called back but declined to say anything about Peterson, telling Vallens he needed to submit a formal request in writing.

“It’s very frustrating,” Vallens said. “My client arguably was illegally arrested and prosecuted, but when I tried to investigate Peterson, I hit a wall.”

The case, he said, highlighted why he rarely tries to extract information about cops through California’s Pitchess laws. He estimated that he attempts to get material on officers in less than 5% of his cases.

It is a common sentiment among defense attorneys, who say the little information they get from judges often leads to dead ends as people cannot be found or refuse to cooperate. The process can take weeks or longer to play out. The pace and marginal payoff, several defense attorneys said, are strong deterrents to filing such motions — especially if a client is being held in jail and could be freed by taking a plea deal.

California’s Supreme Court has concluded that the Pitchess laws do not violate the constitutional rights guaranteed to defendants under the Brady decision.

On the same day in May 2017 that Walgren was reviewing Peterson’s records in his state court chambers, U.S. District Judge Christina A. Snyder held a far different hearing about Peterson’s record in her downtown L.A. courtroom.

I want to make clear that if there’s something that hasn’t been produced, then I expect it to be produced.

— U.S. District Judge Christina A. Snyder

Attorneys for Cesar Castillo Flores and Manuel Moreno, whom Peterson had caught with nearly 9 pounds of methamphetamine and a gun, were arguing that the drugs and weapon should be thrown out as evidence. Peterson, they contended, had violated the men’s constitutional rights by stopping and searching their car without justification.

At that hearing, and a similar one a few weeks earlier, Snyder questioned whether the government had provided the defense all the information about Peterson that the law required.

Saying Peterson’s credibility was “on the line,” the federal judge told prosecutors, “I want to make clear that if there’s something that hasn’t been produced, then I expect it to be produced.”

Because federal prosecutors must adhere strictly to the rules set out by the Brady case and are not beholden to a state’s police privacy laws, they can review an officer’s personnel records.

In a nod to California’s strict rules, the judge barred any public discussion of Peterson’s disciplinary history. But at the hearing and in a written order, she referenced two incidents in Peterson’s file that had resulted in punishment — one from 1998 and another in 2002.

In one of the incidents, Snyder said, Peterson had been suspended for breaking a department rule and being “less than truthful” in some way. The judge did not describe the other instance of misconduct, but defense attorneys claimed in a court filing that Peterson had been found “lying to his supervisors regarding the … misconduct” in both episodes.

A prosecutor assured Snyder the government had handed over the records from the two incidents. The government also disclosed documents from an investigation into whether Peterson had lied about a 2014 traffic stop.

In that case, Peterson wrote a report saying he obtained consent from a driver to search a car that turned out to be carrying 3 pounds of methamphetamine. But after the deputy twice amended his account amid questions over how he got permission for the search from the Spanish-speaking motorist, the prosecutor asked the judge to dismiss the charges, according to law enforcement records reviewed by The Times.

Afterward, Sheriff’s Department officials opened an investigation into whether Peterson had committed perjury, district attorney records show. The district attorney’s office decided against charging Peterson, concluding that there was no evidence he knowingly falsified his report and that the deputy’s accounts were not necessarily inconsistent. A Sheriff’s Department spokeswoman said “appropriate administrative action was taken” after the investigation, but she did not say what discipline, if any, was imposed.

After disclosing the personnel reports about Peterson, federal prosecutors in the case against Flores and Moreno opted not to call the deputy to testify about the traffic stop. Instead, they argued that footage from the camera in Peterson’s car showed he had been justified in stopping and searching the men’s vehicle.

Snyder disagreed, saying the video was inconclusive. She tossed out the drugs and gun as evidence, and prosecutors dismissed the case.

The government dismissed seven of the 10 federal cases based on Peterson’s arrests and has not filed a new case involving the deputy in more than a year.

Shortly after Peterson’s last two federal cases were dismissed in October, Sheriff’s Department officials removed him from his specialized assignment patrolling the 5 Freeway for drug traffickers. He was reassigned to a post ticketing truck drivers on city streets in Santa Clarita.

Back in state court, however, Peterson’s past behavior remained largely unknown.

The case against Mercado — the man Peterson arrested after finding the secret compartment — had yet to go to trial when The Times published a story last year detailing some of the federal drug cases that had fallen apart due to questions about the deputy’s credibility.

Vallens, Mercado’s attorney, said that within a few days of the article, a county prosecutor called with an offer to reduce the gun and drug trafficking charges against his client to a minor traffic violation that came with no jail time. The deal was made because of an “insufficiency of evidence,” a spokeswoman for the district attorney’s office told The Times.

Mercado, who works as a plumber in Stockton, insists he was innocent and said he remains angry that he was ever prosecuted.

“I could have lost everything, for what? Nothing,” the 24-year-old said.

His attorney never learned why, after seeking information on Peterson, he was given the name of a prosecutor in the U.S. attorney’s office. But he said one thing was clear: Had the case gone to trial, Vallens would have known little, if anything, about the deputy’s disciplinary history.

“Those are the rules,” he said.

Times staff writer Ruben Vives contributed to this report.

Twitter: @joelrubin

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.