As California’s deadliest wildfire closed in, evacuation orders were slow to arrive

- Share via

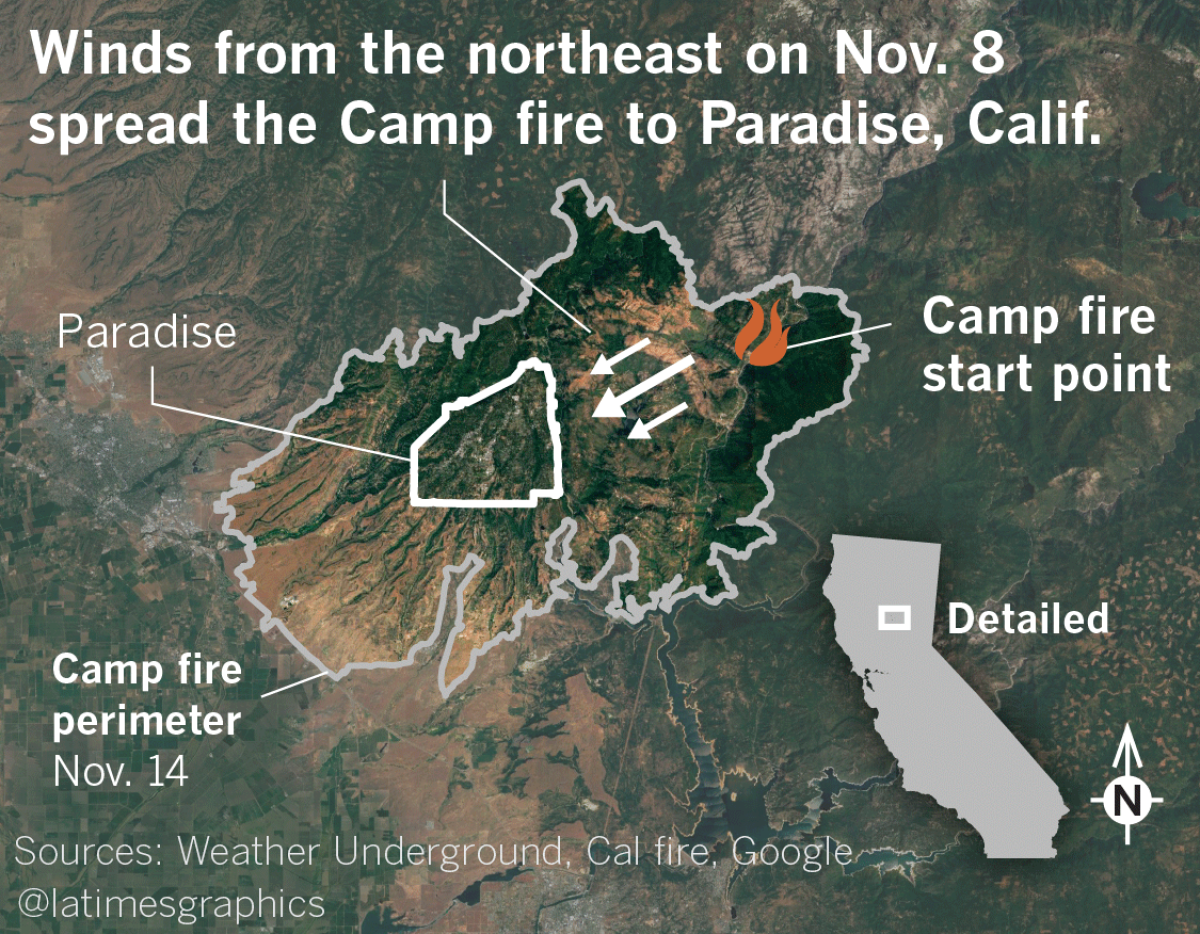

Reporting from Paradise, Calif. — When the Camp fire barreled toward this Sierra foothill town last Thursday morning, officials had a crucial choice to make right away: How much of Paradise should be evacuated?

The decision was complicated by history and topography. Paradise sits on a hilltop and is hemmed in by canyons, with only four narrow winding routes to flee to safety. During its last major fire in 2008, authorities evacuated so many people that roads became dangerously clogged.

So this time, they decided not to immediately undergo a full-scale evacuation, hoping to get residents out of neighborhoods closest to the fires first before the roads became gridlocked.

But it soon became clear that the fire was moving too fast for that plan, and that the whole town was in jeopardy. A full-scale evacuation order was issued at 9:17 a.m., but by then the fire was already consuming the town.

At least 56 people were killed — most of them in their homes, some trying to flee in their cars and others outside, desperately seeking shelter from the flames. More than 10,000 structures were lost in what is by far the worst wildfire in California history.

It’s unclear how much a different evacuation strategy would have changed the outcome of the fire, which was fueled by intense wind gusts of up to 52 mph and record dry vegetation in an area notoriously vulnerable to fires and wind-blown embers.

But the level of destruction and death is sure to make Paradise a grim lesson for agencies trying to improve emergency alerts and evacuations from fires as well as floods, mudslides and other natural disasters.

The death toll from natural disasters in California in the last year has been enormous, with nearly 40 killed in the wine country and Mendocino County fires and more than 20 in the Montecito mudslides. Officials acknowledged shortcomings in the efforts to get people out of harm’s way.

In the chaos of the Paradise fire, many residents said, they never got warnings by phone from authorities to leave. Some said they got warnings from police driving through their streets using loudspeakers. Others got texts from neighbors. But few said they got official text alerts or phone calls from the government.

The fire was first reported near the community of Pulga — about seven miles from Paradise — about 6:30 a.m. By 7:35 a.m., it had reached the nearby hamlet of Concow.

The first evacuation order for Paradise came at 8 a.m., a minute after the first flames were spotted in town. The order was limited to the eastern side of Paradise. The hope was to get the residents closest to fire out immediately, with the rest of the town to follow if needed.

But the fire was simply moving too fast.

“The fire had already outrun us,” said John Messina, California Department of Fire and Forestry Protection battalion chief for Butte County.

The evacuation orders were sent using a phone system called CodeRed, which covers all landlines as well as cellphone numbers voluntarily submitted by residents. But the system doesn’t cover all phones in the town. “In the town of Paradise, I think we’d be lucky to say 25% or 30%” of phone lines are in the system — and that’s after local officials urge residents to sign up, said Jim Broshears, who directs Paradise’s emergency operations center.

Also, the system can reach only so many phones per hour. “I can’t give you the raw numbers, but there’s a capacity per hour of calls. So CodeRed can’t [make] 12,000 calls at once. It’s really fast, but not this fast,” Broshears said.

These types of systems have been criticized because they reach so few people. Instead, some safety experts have advocated using the federal government’s Wireless Emergency Alert system, which sends Amber Alert-style warnings to cellphones within a certain geographical area. But the system was not used during several California disasters, including the wine country fires and the heavy flooding that hit San Jose.

James Gore, chairman of the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors, said government is failing when officials don’t do a good job of communicating an incoming hazard.

“If people are already getting word on Facebook, and there’s nothing coming out of your government, then you’ve failed,” said Gore, whose county has begun to buy fire cameras that can sense the movement of blazes by heat and is seeking to purchase air sirens for parts of the county without cell coverage. “If you’re more worried about the crisis you could cause than the crisis that is upon you, then you have failed.”

In Paradise, Broshears said officials did not employ the Wireless Emergency Alert system because they initially wanted to stagger the evacuations by neighborhood. He also said that Amber Alert-style alerts do “not go to every phone at the same time.”

According to the Federal Communications Commission, Wireless Emergency Alerts are broadcast to coverage areas that best approximate the zone of an emergency; mobile devices in the alert zone will receive the alert. There has been criticism that the geographical targeting of the system is not terribly precise, and in late 2019, wireless carriers are supposed to improve geo-targeting of the alerts.

During the recent test of the presidential alert distributed through the Wireless Emergency Alert system, the average delay in users’ receiving a text message was about 22 seconds.

Because of its vulnerability to fire, Paradise has debated the best evacuation strategy for years.

The idea of staggering evacuations was discussed in the wake of the 2008 fire that burned dozens of homes, county documents reviewed by The Times show. After the fire, some officials felt that residents were “over-evacuated” and that that needlessly clogged roads.

But the documents also show several instances in which county emergency officials warned that they might have to quickly evacuate the entire town.

Many Paradise residents said they were baffled by the lack of a warning.

“I assumed if something were to happen, there’d be an alert on your cellphone,” said Alexandria Wilson, 21. Neither she nor any of her 10 relatives now packed into a home in Applegate who all lost their homes in Paradise had ever heard of Butte County’s CodeRed emergency alert program.

Only two of them received warnings and those were from a police officer driving down the road telling people to evacuate.

Instead, Wilson’s 10-year-old brother, Eden, was coordinating an evacuation effort. Savvy with a cellphone, he was texting and calling everyone and telling them to rendezvous at a Burger King in Chico.

“Nobody should have to get a call from a 10-year-old,” said Jacob Golden, Wilson’s boyfriend.

Serna and St. John reported from Paradise and Lin from Los Angeles. Bettina Boxall and Sonali Kohli contributed to this report from Los Angeles.

UPDATES:

7 a.m.: Updated with new map.

Originally posted at 7:45 p.m. Wednesday

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.