From the Archives: The road to recovery for Robert Dorsey, whose three roommates died in the Northridge earthquake

- Share via

Editor’s note: This story was originally published in the Los Angeles Times on Feb. 15, 1994.

Just a month after his three roommates died around him, Robert Dorsey, 25, went back to classes at Cal State Northridge on Monday.

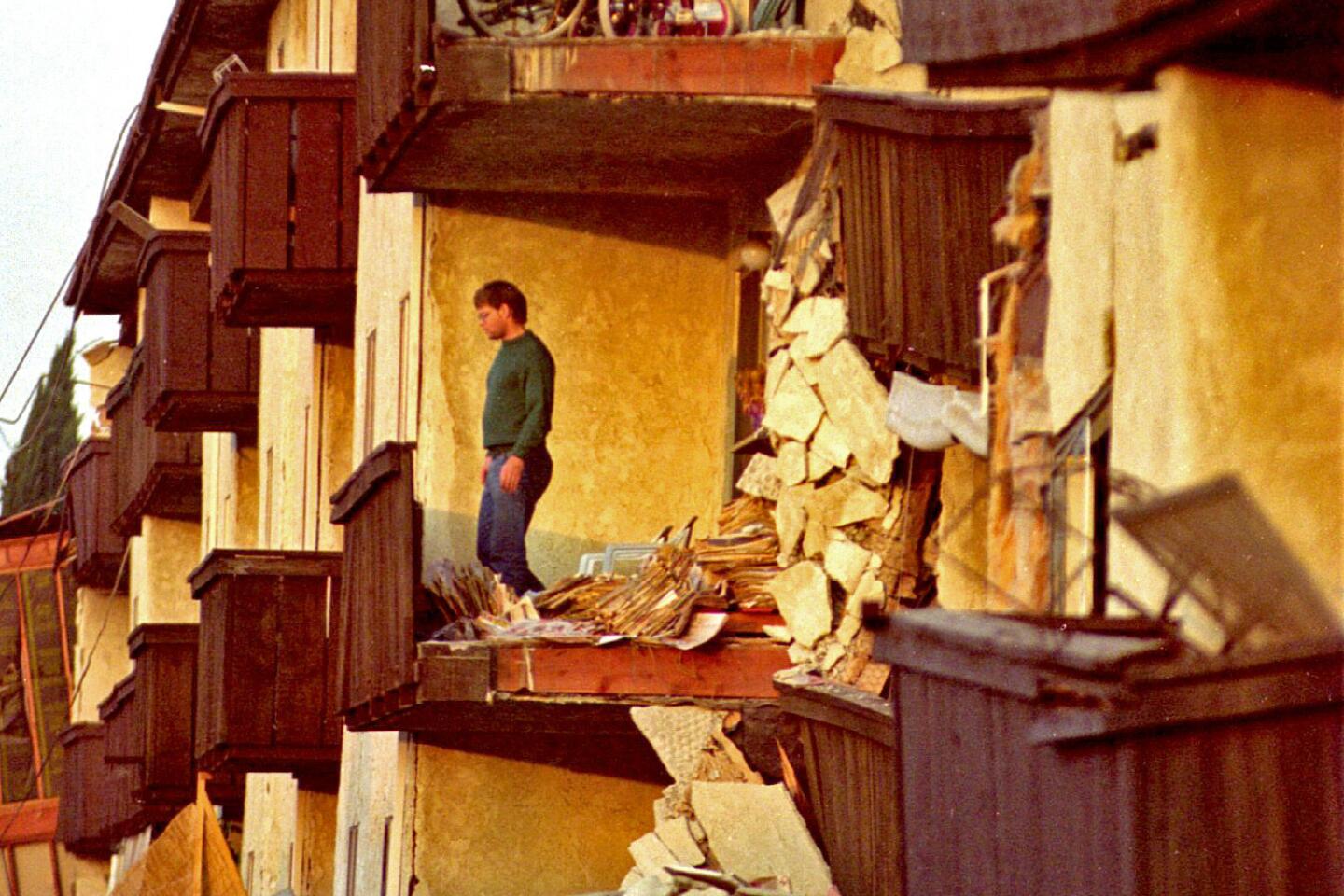

He still has trouble sleeping, still plays the scenes endlessly in his head: his ground-level apartment crushed under two upper stories of the collapsed Northridge Meadows complex, his roommates suffocated in their beds only yards away.

The rib he cracked trying to shove himself out from under the fallen ceiling is healing. He can walk without crutches on the leg that was compressed so hard and so long he thought it would be amputated. He no longer coughs up the little white balls that formed in his throat from inhaling drywall dust while pinned in the blackness.

Even before the Jan. 17 earthquake killed 16 of his friends and neighbors at Northridge Meadows, Dorsey had survived high-speed motorcycle crashes and a fiery car explosion. He survived the Persian Gulf War as an Army machine-gunner.

Now he is the lone survivor of Apartment 104.

Despite his roommates’ deaths, Dorsey was eager to get back to his computer science and math classes at CSUN, he said.

College is Dorsey’s top priority. In his first semester last fall, he earned a 4.0 grade point average. He hopes to transfer to UCLA or UC Berkeley in two years, and later obtain a master’s degree.

And he feels no guilt, he said, over emerging alive from Apartment 104. Trapped himself, there was nothing he could have done to save his roommates, he said, and he takes comfort in that knowledge.

“Certain events I go through and I accept, and then I get on with my life,” said Dorsey, a slim man with reddish-blond hair, an earring and a quiet, matter-of-fact manner.

“I walk by that (apartment complex) building and two minutes later I’m on my way, thinking about what I’ve got to get done.”

Discharged last summer after six years in the Army, in which he enlisted specifically to get college money, Dorsey enrolled at Cal State Northridge in September. He moved into a dorm where he met Manuel Sandoval, 24, a fellow computer science major who soon became his best friend.

Related: A big earthquake would topple countless buildings, but many cities ignore the danger »

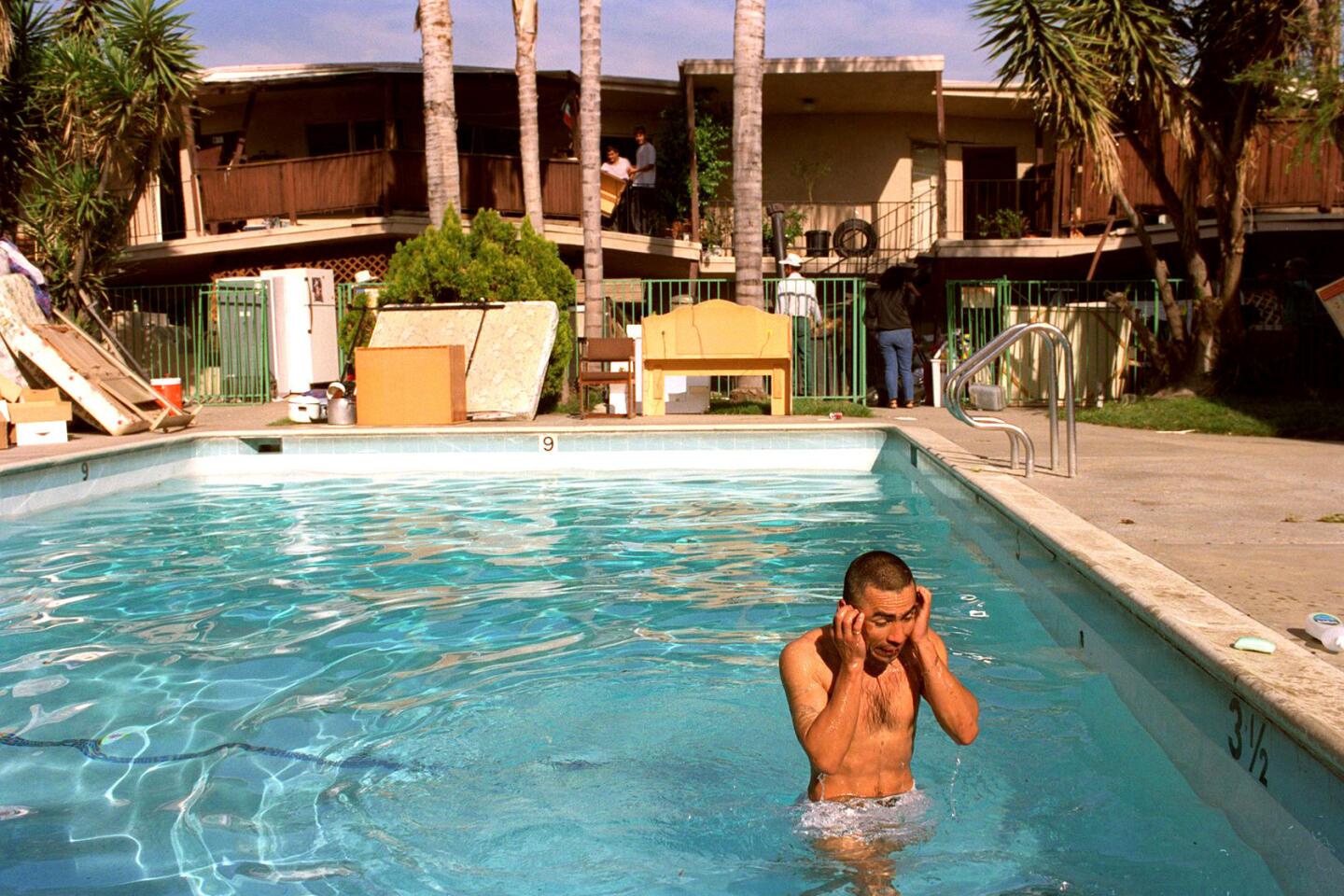

By Christmas break, the pair had decided to find a cheaper place to live. After checking out dozens of buildings, they settled on the Northridge Meadows, a well-maintained complex that sported a courtyard pool, putting green and barbecue pits and advertised “resort-style living.”

They moved in two days before the quake, joining two other roommates who had arrived five days earlier, Jaime Reyes, a 19-year-old CSUN student, and his new girlfriend, Myrna Velazquez, an 18-year-old Valley College student.

The night before the quake, Dorsey and Sandoval cooked a chicken dinner and relaxed in front of the TV. By 1 a.m. Monday, they were asleep in their bedroom, and Reyes and Velazquez were asleep in their smaller room nearby.

When the quake struck at 4:31 a.m., Dorsey leaped out of bed and ran toward the door frame. But the wildly heaving floor pitched him atop a three-foot-high metal filing cabinet.

Seconds later, the roof caved in, pinning him helplessly, face-down.

“I was smashed into the filing cabinet like somebody stepping on a Coke can, crushed right into it,” he said.

Dorsey had the air knocked out of him and could not breathe for a minute or so. Terrified that he would suffocate, he heaved himself a few inches forward, yanking his chest off the filing cabinet so he could breathe. He pushed so hard he cracked a rib.

Just as he was feeling a bit safer, a sharp aftershock brought the ceiling down even more, further constricting his lungs. He could see only 12 inches of space between the floor and ceiling.

“I was taking half breaths,” he said. “And every aftershock after that, I went from half breaths to quarter breaths. I realized that if they don’t get me out of here soon, I’ll go from quarter breaths to eighth breaths to no breaths at all.”

One of his legs, jammed under debris, felt like it had lost circulation. When he touched it, he felt nothing.

See the Los Angeles Times front pages in the days following the Northridge earthquake »

Outside on Reseda Boulevard, fire trucks raced by, sirens wailing. But none stopped. He realized the quake probably had wrecked lots of apartment buildings, and figured that he might be trapped for days.

Dorsey tried to stay calm. To get excited meant his heart and lungs worked faster, and that only produced more pain. But when he thought of his roommates, he began to scream.

“I just kept screaming out their names, saying, ‘Talk to me, tell me you’re alive, tell me you’re in good condition,’” he said.

Sandoval, dead in his bed about 15 feet away, made no sound.

Dorsey felt himself envying his three dead roommates.

“Tell you the truth, I felt jealous. Because I was so sure that I was going to die that I was thinking, ‘Gee, I wish I could have gone painless and quick like that.’”

Dorsey heard voices from the sidewalk, people talking and laughing just a few yards away. But when he started yelling for help, no one responded.

“They all stopped talking. It was like bystander apathy. They all stood around waiting for somebody else to come over.” One woman, he said, even told him to “stop your whining.”

Eventually, a man came to Dorsey’s aid. He told Dorsey that Fire Department rescue crews were en route. Then he began chipping away at the debris with a claw hammer.

After they arrived, the fire fighters worked quickly and efficiently. But they apparently did not realize Dorsey’s back was actually jammed against the ceiling, which they were trying to cut through from the apartment above.

A chain saw slashed through the ceiling next to his head. Dorsey shouted to his rescuers that they were in danger of cutting him, and they began slicing only part way through the ceiling and then cracking it with sledgehammers.

Finally, the ceiling was weakened to the point that Dorsey used his arms and back to punch through it. “It was the best push-up I ever did,” he said. Firefighters hauled him out through an apartment window, using a door as a makeshift stretcher.

He had been trapped in the rubble for 2½ hours.

Getting the overwhelming weight of the collapsed ceiling off him, he said, was “beyond relief.”

“It was just like being tortured your whole life, and suddenly not knowing pain,” he said.

But within minutes, his body filled with new pain — from his cracked rib, compressed leg and assorted cuts and bruises. Clad only in shorts and a tank top, he began shaking violently in the chill morning. He felt himself slipping into shock.

A doctor examined him and sent him by ambulance to Northridge Hospital Medical Center.

At the quake-damaged hospital, doctors and nurses in the parking lot were frantically seeing which patients most needed medical care. Dorsey had his chest and leg X-rayed and then, since he had no life-threatening injuries, was given crutches and asked to leave. Someone said they needed his bed.

With no money and no shoes, Dorsey took a free hospital shuttle bus to the Cal State dorms, hoping to find some shelter. But the dorms were closed. Badly dehydrated and in pain, Dorsey blacked out three times.

Eventually, another Cal State student drove him back to the hospital, where he huddled overnight, sleepless, on a small mattress in the lobby. His mother arrived the next morning and took him to his parents’ home in Petaluma, north of San Francisco.

For two weeks, he could not sleep. He would jump out of bed in the middle of the night, hugging the wall and “trying to hold it up,” mistakenly believing another quake had hit.

“When I’m wide awake … I have no problem. It’s business as usual,” he said. “But at night, you just can’t fool yourself. Things start to come back. You start to rehash everything.”

But Dorsey doesn’t expect the flashbacks and night fears to continue for long.

“I’ve had a lot of experience with bad, traumatic things. I’ve come close to death several times,” he said.

“But I have very, very good coping skills. This is just one more thing. And I think I can deal with it.”

From the Archives: An emerging Northridge earthquake death toll »

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.