Study finds broad public, police support for release of LAPD shooting video, but sharp split over timing

- Share via

The 2014 decision to place body cameras on thousands of officers landed the Los Angeles Police Department in the middle of an intense back-and-forth over whether the recordings from those cameras should be made public.

More cameras were deployed and more recordings collected. Police chiefs across the country, including LAPD Chief Charlie Beck, were pressured to share video after controversial shootings by officers. And the focus of that debate steadily changed.

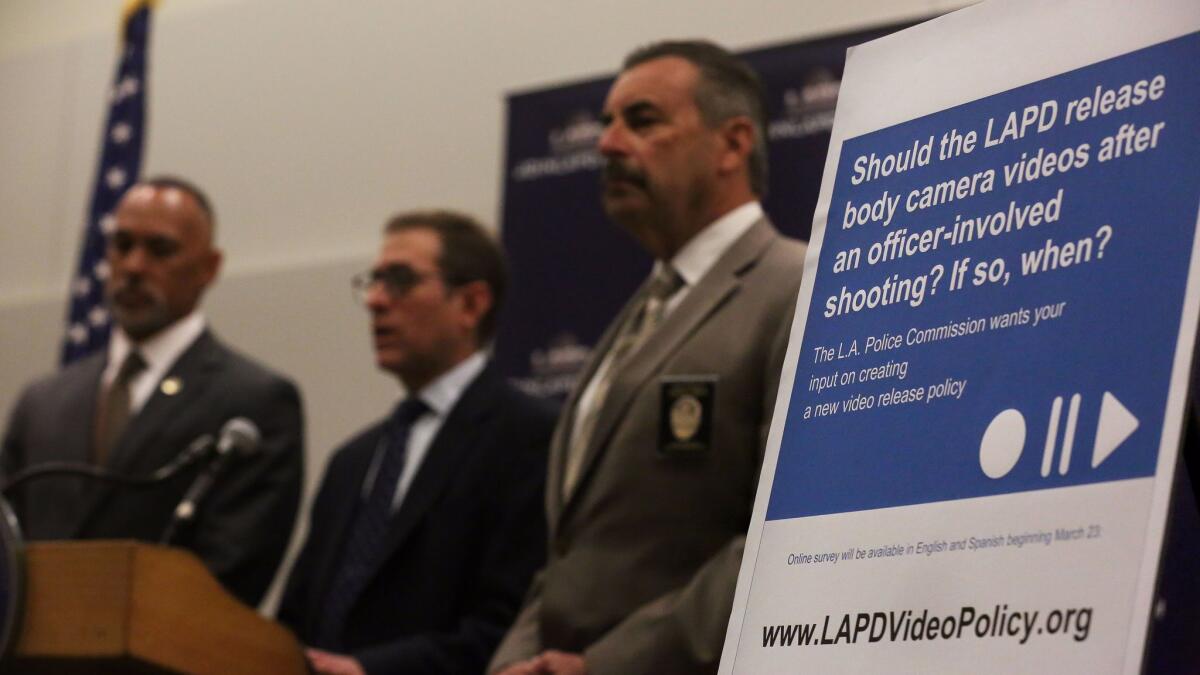

Now, the question no longer seems to be whether video will become public. Instead, officials in Los Angeles are trying to figure out how and when to release recordings, some of which may have captured incendiary encounters or be used in prosecutions.

A new report released Tuesday reflected that shift, showing broad support from both the public and police for releasing footage from police shootings. Of almost 3,200 people questioned, 84% said the recordings should become public — including nearly two-thirds of people who worked in law enforcement.

The 53-page report comes from the Policing Project, a nonprofit based at the New York University School of Law, which the Los Angeles Police Commission brought in months ago when it decided to revisit the LAPD’s rules for releasing video after critical incidents.

The department almost never makes such videos public outside of court, a stance that has been heavily criticized.

The Police Commission, the civilian panel that oversees the LAPD and sets its policies, has yet to vote on new rules for releasing LAPD video or even draft a proposal for further discussion. That should happen in the coming weeks, commissioners said Tuesday.

Whatever rules the five-person commission settles on will cover recordings captured by body cameras, patrol car cameras or otherwise collected during an investigation.

The Policing Project collected feedback this spring from community meetings, focus groups with LAPD officers and command staff, and written comments submitted by more than two dozen organizations including the American Civil Liberties Union, First Amendment Coalition and the Los Angeles Times.

Much of the report focused on questionnaires collected from 3,200 people who said they lived, worked or went to school in Los Angeles. About 530 of those people identified themselves as law enforcement officers.

Though the questionnaire asked the most basic question — should video from a police shooting be made public? — it also dug into the nuances now driving the debate, including who should release the footage and when.

“It’s all of those secondary questions that are going to be the hard ones for the commission to answer,” said Maria Ponomarenko, deputy director of the Policing Project.

Although there was widespread support for releasing footage — black respondents felt even more strongly than others, with 81% saying video should definitely be released — there was a striking split when it came to timing.

Nearly half of the public respondents said that if video were automatically released, it should happen within 30 days of the incident. Another 16% said the footage should be made public within 60 days.

But nearly two-thirds of officers said they believed video should be released after the district attorney decides whether to file charges in connection with the incident — a process that often takes a year or more.

In one of the most high-profile examples, Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey has still not said whether she will charge the LAPD officer who fatally shot an unarmed man near the Venice boardwalk 2½ years ago.

Lacey submitted written comments to the Policing Project, according to the report. She “did not take a position on whether video should be public,” the report said, “but urged that video not be released until the district attorney’s office has decided whether to bring charges against any of the individuals involved.”

Just over 60% of the public said they favored a policy in which video would automatically be released within 60 days. That drew the strongest opposition from law enforcement, almost two-thirds of whom said they strongly opposed that idea.

But both police and the public were skeptical that public officials would make the right call if the decision were made on a case-by-case basis, the report said. Respondents said they worried that those officials would be swayed by politics or rule in a way that benefited themselves or their organizations.

Police commissioners said the findings would provide valuable insight as they move forward.

“Clearly there is agreement between members of the public and people in law enforcement that this footage in these critical incidents should be released,” said Matt Johnson, the commission’s vice president. “Now it becomes a matter of determining the proper timing and process.”

Johnson served as the panel’s president until his term ended Tuesday, when commissioners unanimously elected Steve Soboroff to the job.

But the debate is not over. Beck, who has expressed concerns over protecting victims’ privacy and investigations, said he supported video release in “the right parameters.” The chief said he believed video should be released when the LAPD could say more about whatever happened using witness statements, coroner’s reports, forensic analysis and other video.

“That’s the thing that I worry about the most, is that we will get to a place where we just release raw evidence with no context,” he said. “The release of body-worn video without the context … is not a good idea. And I think it would actually cause more harm than good.”

The union representing rank-and-file officers cautioned that footage “used inappropriately” could hamper investigations, improperly influence potential jurors or invade the privacy of innocent people.

“That is too high a price to pay in the name of transparency,” the union said in a statement.

Others who attended Tuesday’s commission meeting called for a more open policy. Peter Bibring, a senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, said video should be automatically shared within 30 days unless there were specific reasons why an investigation couldn’t be completed within that time.

“I don’t think anybody thinks that the body camera release policy is going to be a complete answer to justice, to accountability, to building trust between the department and the community,” Bibring said. “But it’s an important part of the equation.”

ALSO

Fast-moving wildfire burns 2,000 acres, damaging one home as hundreds evacuated

Berkeley police seize 677 pounds of drugs after stumbling onto psychedelic mushroom operation

Deal for new city at Newhall Ranch fuels development boom transforming northern L.A. County

UPDATES:

7:35 p.m.: This article was updated with comments from a police commissioner, LAPD Chief Charlie Beck and the deputy director of the Policing Project.

2:10 p.m.: This story was updated with information from the Policing Project’s report.

This story was originally published at 5 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.