L.A. County ends contract with ICE, then OKs future collaboration

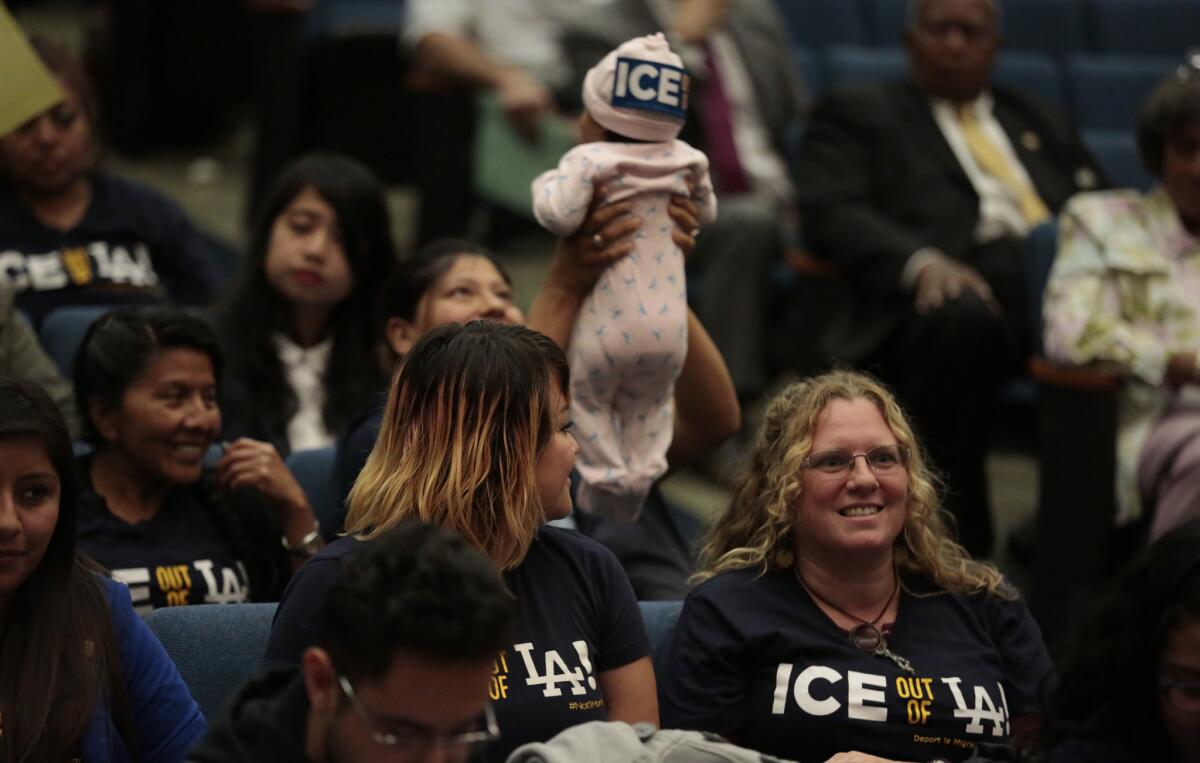

Immigration agents will be allowed back into Los Angeles County jails to identify deportable inmates under a policy made public Tuesday by Sheriff Jim McDonnell. Above, people attend a Board of Supervisors meeting in May when a previous policy allowing such cooperation was ended.

- Share via

Los Angeles County supervisors voted Tuesday to end a controversial program that places immigration agents inside county jails to determine whether inmates are deportable.

On a 3-2 vote, the Board of Supervisors severed the county’s contract with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which since 2005 has allowed ICE agents to work daily inside jails and has trained jail employees to assess the immigration status of inmates.

But the county is not ending its cooperation with immigration agents altogether.

On Tuesday the board passed a separate measure expressing its support for ICE’s newest jails initiative, known as the Priority Enforcement Program, or PEP.

Obama announced the creation of PEP last fall during a major immigration speech in which he promised to shift immigration enforcement to target “felons, not families.”

It replaced an earlier program, Secure Communities, which Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson said had “become a symbol for general hostility toward the enforcement of our immigration laws.”

Under Secure Communities, immigration agents checked the fingerprints of every inmate booked in a local jail to determine whether they were in the country illegally. ICE then asked jails to hold certain inmates — often beyond the length of their jail sentence — so they could be transferred into federal custody.

Immigrant activists complained that the program eroded immigrants’ trust in police and resulted in the deportations of people who had committed no crime or only minor infractions.

After an Oregon judge last year found that it was unconstitutional for jails to hold inmates past their release date, many counties, including Los Angeles, stopped cooperating with ICE’s requests altogether.

In the current fiscal year, which began in October, local authorities have rejected 4,230 out of 58,500 requests, according to figures provided by ICE. Close to half of the denials were from the Los Angeles area.

Under the new PEP initiative, jails will now be asked to notify federal authorities when someone will be released, so agents can be waiting. This time, the agency says, local officials can trust that only people convicted of serious crimes will be targeted.

In recent weeks, top Homeland Security officials have been touring the country to try to generate support for the new program and reenlist police chiefs and mayors in the cause of deporting people convicted of crimes.

But many advocates and local officials say the new program falls short of resolving the issues that plagued Secure Communities.

“They presented it as a kinder and gentler way for ICE to collaborate with local police,” said Los Angeles County Supervisor Sheila Kuehl, who met last week with ICE Director Sarah Saldana and Homeland Security Deputy Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas. “I told them it’s not kinder or gentler enough.”

Kuehl voted against Tuesday’s motion to support PEP.

The root of the problem is that ICE continues to “mine the criminal justice system” to meet deportation targets, said Chris Newman of the National Day Laborer Organizing Network, who along with other advocates also met last week with Saldana and Mayorkas. As ICE tries to meet those goals, critics say, the agency will probably deport people convicted of less serious offenses because many of the most serious criminals are serving long prison terms.

“They really, really want to have that talking point of deporting ‘felons not families,’” Newman said. “At a time when everyone’s talking criminal justice reform, immigration enforcement is going in the opposite direction.”

ICE says it has already refined its enforcement priorities and will no longer make a priority of people who have committed no other crime besides being in the country illegally. But advocates say too many people are still being deported because of minor offenses and long-ago convictions.

The agency’s data show that most of the 58,500 detainer requests this fiscal year didn’t target people convicted of the most serious crimes, called aggravated felonies. There are 16,384 people in that category. Nearly 14,000 were convicted only of misdemeanors, the figures show, and more than 20,746 don’t fit any of the three categories designated by Obama as priorities for deportation.

Some of those in the last category might have been accused of serious crimes but not convicted, an agency spokeswoman said.

Chris Rickerd, policy counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union in Washington, said the figures showing many detainers in low-priority categories were “really disturbing” and suggested the department hadn’t yet changed its approach. “I don’t think they’ve been accountable and transparent about who’s being deported,” he said.

Immigration officials have complained that it is harder to grab criminals if local officials won’t cooperate.

“That was getting to be a bigger and bigger problem in terms of our ability to get at the criminals,” Johnson said last month. “The new enforcement program takes two to dance.”

L.A. County Supervisor Hilda Solis, who co-sponsored Tuesday’s motion in support of PEP, said the county will take a “trust, but verify” approach to the new ICE program.

She said Sheriff Jim McDonnell will be empowered to make sure ICE is notified of the release of only very serious criminals. If PEP poses problems, Solis said, “we can always opt out.”

Tanfani reported from Washington and Linthicum from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.