Grim Sleeper verdicts bring justice to forgotten victims of serial killer, families say

- Share via

Nearly 30 years after the first victim was found sprawled in a South Los Angeles alley, the man authorities believed was the “Grim Sleeper” serial killer was found guilty Thursday of murdering nine women and a teenage girl in a series of slayings that took decades to connect.

The verdict means that Lonnie David Franklin Jr., a former Los Angeles police garage attendant and city garbage collector, officially becomes one of California’s most prolific serial killers. The murder counts at his trial spanned from 1985 to 2007, with a gap of 14 years from 1988 that earned him his infamous nickname.

For families of the victims the jury’s decision caps years of anguish over whether the killer would face justice, and bitter feelings that authorities didn’t do enough in the early years to solve the murders.

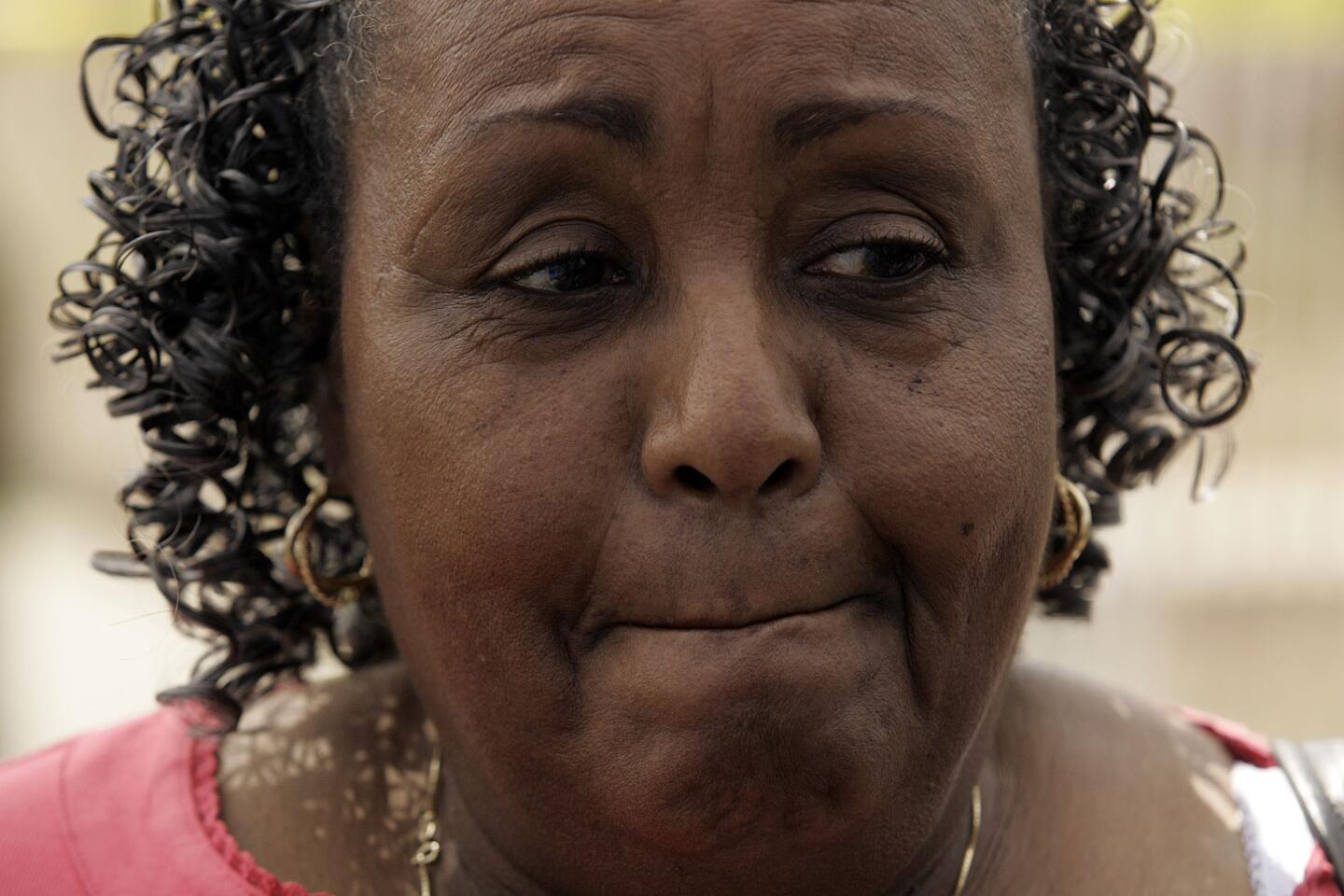

“I can’t even begin to explain. You wait so long and you don’t think it will come. You knew in your heart it would be this, but it’s surreal,” said Samara Herard, sister of Princess Berthomieux, who at age 15 was found strangled and beaten in 2002 in an Inglewood alley. “She deserved to live a full life. I’m here for her.”

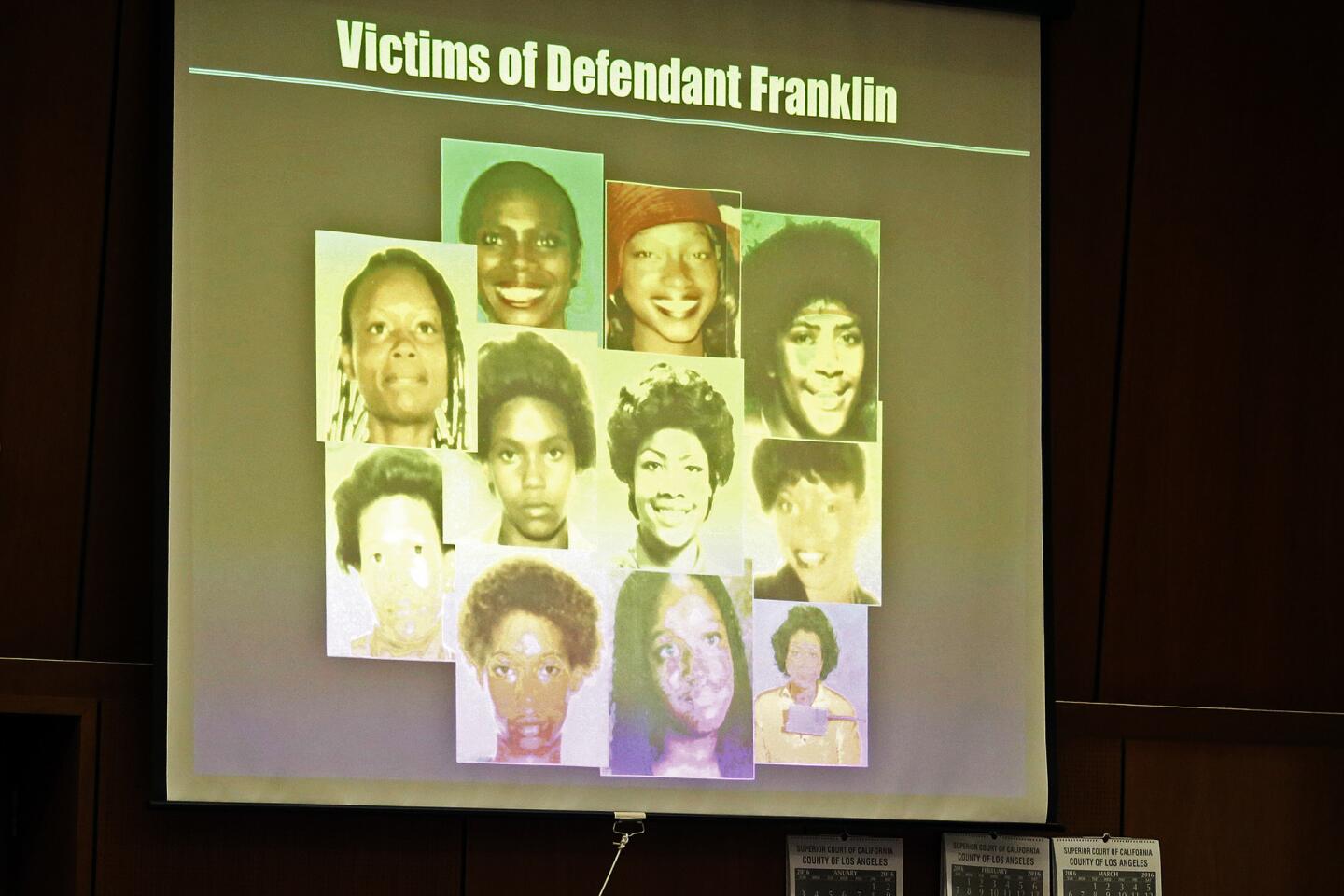

All the victims were young and black, some leading troubled lives during the chaotic 1980s in South L.A. Many of the women were left strewn along a corridor in the Manchester Square neighborhood, their partially dressed or naked bodies — some decomposing — found amid the filth and garbage of alleyways.

All had been discarded without identification, and each was initially labeled Jane Doe.

“They suffered from the same frailties and the same imperfections that all humans do, and they had the same hopes and the same dreams for their futures that we all have,” Deputy Dist. Atty. Beth Silverman told jurors during closing arguments in the trial.

“None of them deserved to be brutally dumped like trash as if their lives had no meaning.”

The killing of the women, some of whom were drug addicts or worked as prostitutes, failed to elicit the same alarm that put Los Angeles on high alert during rampages of other prolific serial killers in the Southland, such as the so-called Hillside Strangler or Richard Ramirez, who was dubbed the Nightstalker.

The deaths attributed to the Grim Sleeper in the mid- to late ‘80s coincided with a surge of homicides linked to the crack cocaine epidemic. In addition, several other serial killers were operating in the same area in those years. Michael Hughes was later convicted of killing seven women, Chester Turner of 14 women and a fetus. Both are on California’s death row.

But the Grim Sleeper proved to be the most persistent. His victims’ deaths would not be connected for decades, and police kept the slayings quiet despite suspicions that a serial killer was stalking young black women.

That decision led to outrage and condemnation from many who attribute Franklin’s longevity as a killer to police indifference.

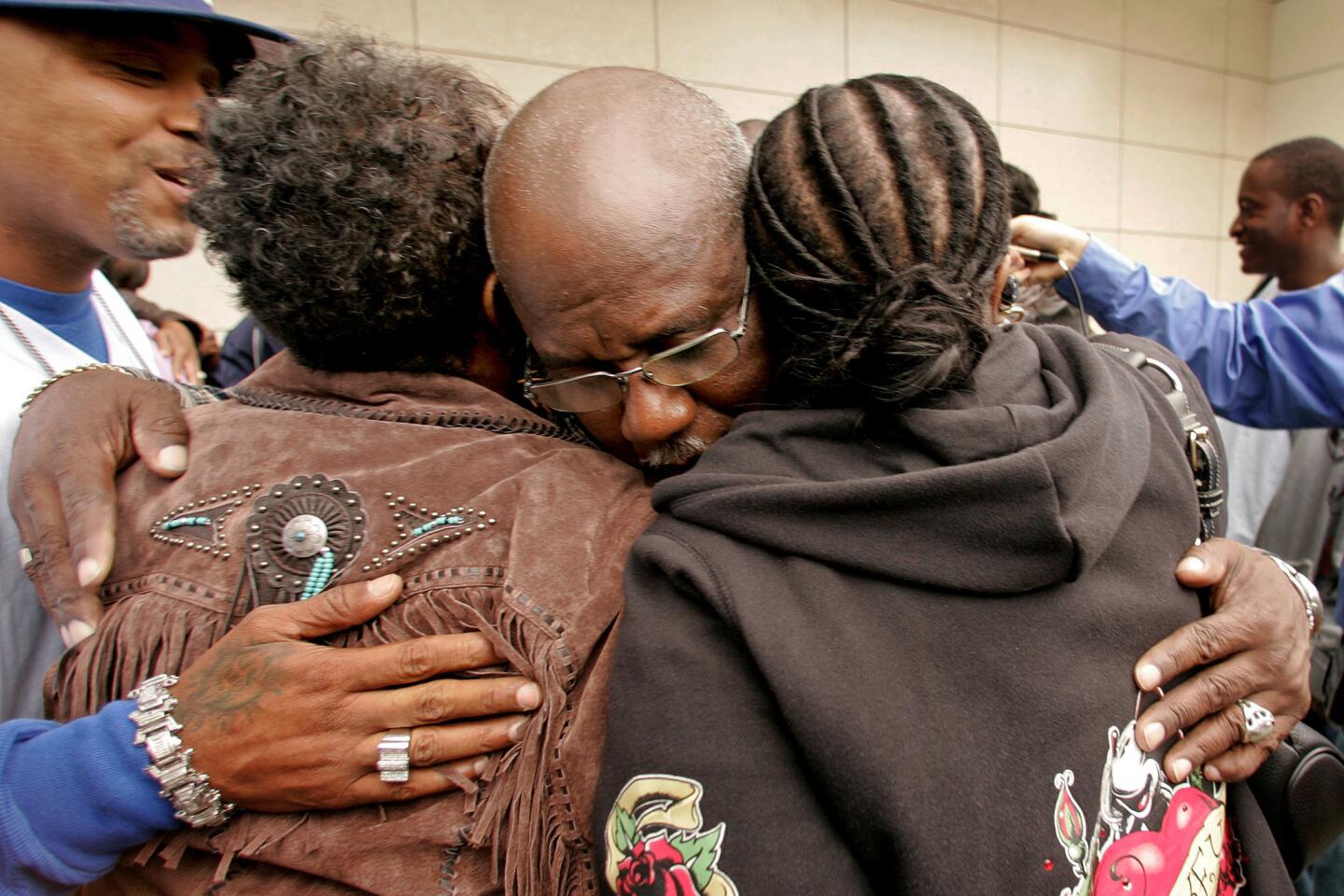

After the verdict, Porter Alexander, his eyes bloodshot and filled with tears, said he has yet to understand how a man could be so cold-blooded.

“He took my baby — it crippled me. But it didn’t stop me. I got that from my daughter,” he said. “What goes around, came around. Now it’s his turn. Eye for an eye.”

Franklin’s fate will be determined in the next phase of the trial when jurors hear evidence to help them decide whether he should be executed or sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Prosecutors are expected to present evidence that Franklin, 63, killed at least five more women for which he wasn’t charged.

The courtroom audience remained mostly silent as the clerk read the 11 guilty verdicts, but with each one another section of spectators would erupt in tears.

The daughter of victim Henrietta Wright, her chin in the air, nodded slowly as the clerk read the guilty verdict in her mother’s killing, tears streaming down her cheeks.

Franklin, 63, remained completely still except for his right foot bouncing quickly up and down. As the verdicts were recited, he stopped and remained still, his eyes fixed on the clerk as she read.

Before the verdict in the nearly three-month trial, Alexander and his wife Mary, whose daughter Alicia Alexander was killed in 1988, interlocked their fingers. Mary Alexander rocked with her eyes closed, tears dripping into her lap as she sat waiting. Porter Alexander clenched his other hand in a fist.

As they heard the verdict in their daughter’s killing, their hands clasped more tightly. Porter opened his fist.

Prosecutors argued that Franklin was connected to each of the 10 slain victims, as well as an 11th who survived, by DNA evidence, ballistics or both. Franklin’s DNA was found on seven victims.

A gun found in Franklin’s home was used to kill one woman, according to court testimony. Police criminalists testified that bullets from eight victims — seven whom were killed and the one who survived — were fired from another weapon that was never recovered. Franklin’s DNA was on the bodies of three of those women, according to testimony.

“The evidence in this case is the voice of the victims who can no longer speak for themselves,” Silverman said during the trial.

Franklin did not testify. The defense argued that other men could have committed the murders, pointing to DNA not belonging to Franklin that was found on some of the women’s bodies, their clothes and the crime scenes.

In his closing argument, defense attorney Seymour Amster suggested that a relative or an associate of Franklin’s who called him “uncle” was responsible.

He seized on testimony by Enietra Washington, the woman believed to be the Grim Sleeper’s only known survivor, who told jurors that she was raped and shot by an assailant nearly 30 years ago. In court, she identified Franklin as her attacker.

Amster, who did not attend the reading of the verdict, pointed to one account Washington gave police in which she said she accepted a ride from a “youngster” in his 20s who told her he needed to make a stop at his uncle’s house to pick up some money. Washington testified that the house where he stopped was Franklin’s home on 81st Street. After the stop, she said, she was sexually assaulted and shot.

Amster said Washington’s description of her attacker did not match Franklin, who would have been 36 at the time.

“It is our position that there is a nephew, or a youngster, who is involved and did each and every murder,” the defense attorney told jurors. He did not name a possible suspect.

The prosecutor mocked the argument as a “grand conspiracy theory,” noting that Amster had waited to raise it until the last day of trial. Silverman pointed out that Washington told police that her attacker took photographs of her. Police later found a photograph of Washington in the wall of Franklin’s garage, Silverman told jurors.

Ballistics tests showed that Washington was shot by the same firearm used to kill seven victims in the case, the prosecutor argued. Franklin was also found guilty of attempted murder for the attack on Washington.

The victims, in the order they died, were: Debra Jackson, 29; Henrietta Wright, 35; Barbara Ware, 23; Bernita Sparks, 25; Mary Lowe, 26; Lachrica Jefferson, 22; Alicia Alexander; Berthomieux; Valerie McCorvey, 35; and Janecia Peters, 25.

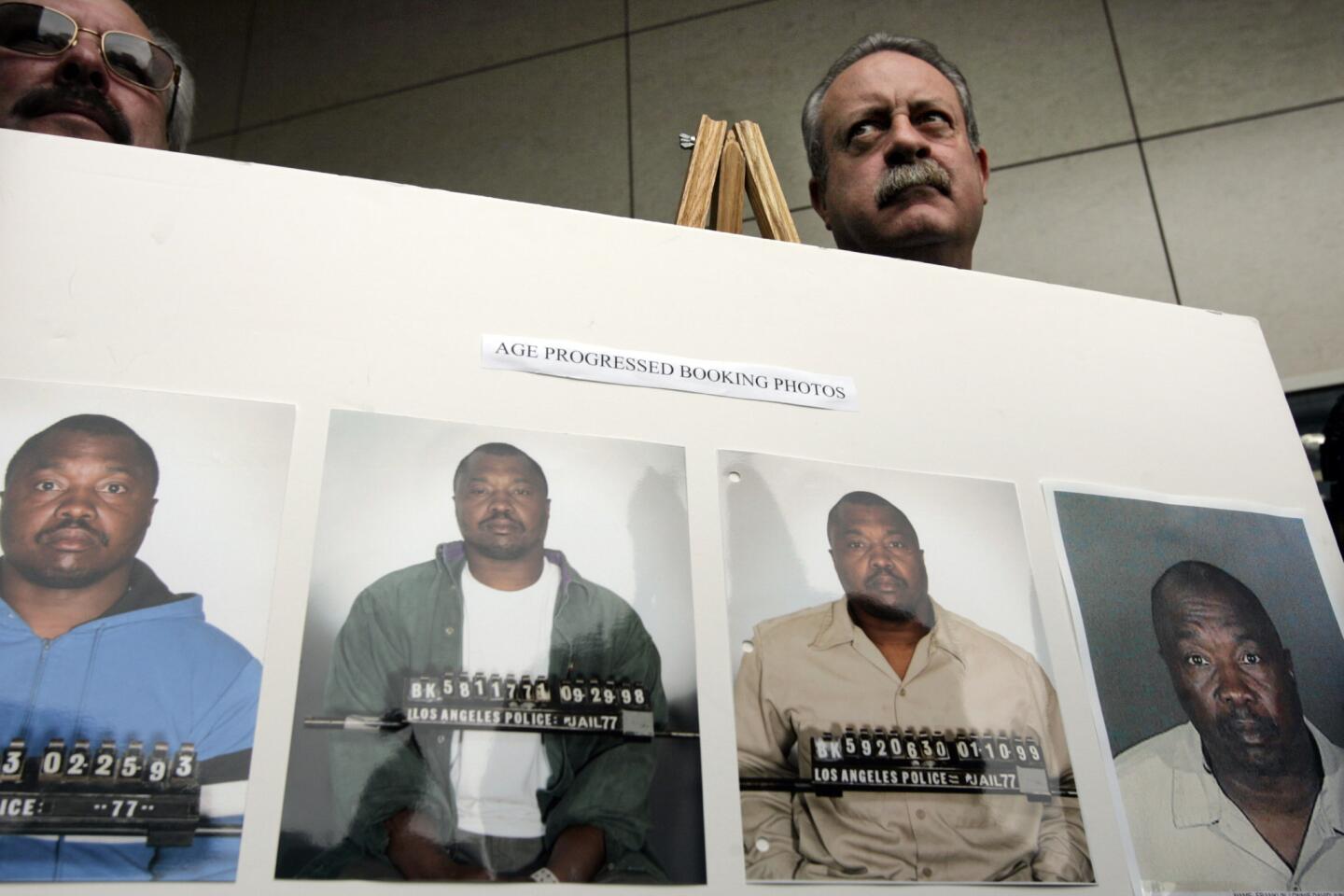

The trial highlighted the difficulty authorities encountered in identifying the perpetrator until breakthroughs in DNA science helped detectives zero in on Franklin. Police began to connect the victims after the discovery of Peters, whose body was found in a garbage bag inside a dumpster in 2007. DNA taken from her crime scene matched evidence from two earlier slayings, prompting investigators to begin matching the DNA with killings from the 1980s and more recent deaths up to the early 2000s.

Investigators, however, did not know to whom the DNA belonged.

In 2008, officials checked DNA taken from state prisoners but didn’t find a match.

A year later, then-state Atty. Gen. Jerry Brown approved a new technique called a “familial search” that allowed officials to check whether a crime suspect’s DNA partly matched that of anyone in the state’s offender DNA database.

Another check produced a partial match to Franklin’s son, whose DNA had been taken when he was arrested in 2008 and charged with firearm and drug offenses.

Investigators focused their efforts on the elder Franklin and launched a surveillance operation.

Jurors were shown a video of an undercover LAPD detective posing as a busboy at a Buena Park pizza restaurant where Franklin was attending a child’s birthday party in 2010. The detective could be seen retrieving a half-eaten slice of pizza, a fork, two napkins, two plastic cups and a piece of chocolate cake from Franklin.

The items were used to analyze his DNA — which matched genetic material found at some of the crime scenes and on the bodies of some of the women.

The next day, Franklin was arrested and authorities launched a search of his green house on 81st Street. There, investigators found inside a dresser drawer a .25-caliber semiautomatic handgun. It was the same weapon, two criminalists testified, that was used to shoot Peters.

Times staff writer Joseph Serna contributed to this report.

For more news on the Grim Sleeper murder trial, follow @sjceasar on Twitter.

ALSO:

Just say yes: Some California law enforcement leaders support legalizing recreational pot

California Supreme Court seems likely to allow parole ballot measure to move ahead

LAPD hacked into iPhone of slain wife of ‘Shield’ actor, documents show

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.