China’s Gobi Desert feeds Yosemite National Park’s forest, study says

- Share via

What does the

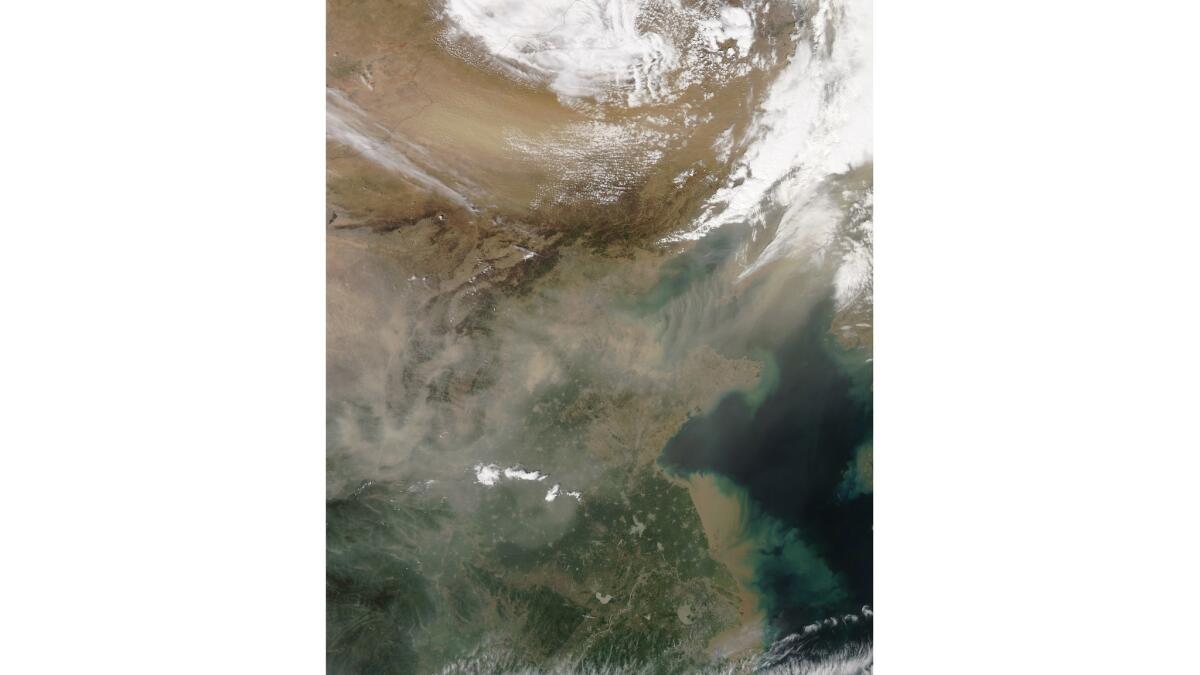

During California’s rainy season, climate scientists say, dust from as far away as the Gobi Desert in Asia is carried by the global jet stream and deposited on top of Yosemite’s granite bedrock, where microscopic material within the dust feeds the vast forests of the Sierra.

The process has been going on for hundreds of thousands of years, but not until recently did scientists aim to understand the impact of that relationship in the Sierra Nevada.

A global nutritional supply chain

In general, plants are supplied nutrients as bedrock is converted into soil, a process that helps regulate life across much of the Earth’s surface. But where that process is lacking — such as in the granite mountains of Yosemite National Park, or the Amazon, where constant rain and flooding wash away nutrients — desert dust can make all the difference.

The Amazon relies on the Sahara Desert in Africa for much of its nutrient supply and scientists suspected that the Sierra Nevada conifers relied on a similar relationship.

Studying the Sierra Nevada dust

So last year, scientists from

But after California’s five-year drought was washed away by the wettest winter in a decade, researchers want to see how the weather has changed the trees’ menu and said they plan to revisit the same test sites in Yosemite next spring.

The research will not only help answer experts’ questions on how the Sierras’ bands of conifer forests filled with sequoias and pines managed to grow for hundreds or thousands of years on nutrient-poor granite, but how they may respond to climate change.

“As you get more warm storms and fewer colder storms, you will see changes just like this hot, drought-caused tree mortality,” said Roger Bales, a UC Merced engineering professor and director of the Sierra Nevada Research Institute.

As it turns out, the last few years were a good time frame in which to examine how climate extremes can affect California’s mountainous ecosystems. UC Merced ecology professor Stephen Hart said that was because it included an average year for precipitation tucked between historically dry and wet years.

Gobi dust rides the jet stream

The team’s research, published in Nature Communications, showed that during the peak of the drought, the forests in the Sierra Nevada foothills and low elevations were fed by dust from the San Joaquin Valley, where withering fields turned brown, lakes evaporated and the earth literally sank due to groundwater pumping.

That dust was chock-full of nutrients like phosphorous, calcium, magnesium and potassium and stood in stark contrast to the material stored in the granite that characterizes Yosemite, which is relatively young and helps shape the older valley floor, Hart said.

The earth that once covered Yosemite’s granite peaks was worn away long ago during mountain formation. Much of that matter was washed downhill during storms — which is why the Central Valley is such a fertile breadbasket, Hart said.

So researchers were not only surprised to find nutrient-rich dust at the mountain’s higher elevations, they were also surprised to find that it came from another continent.

The team collected the dust from marbles that were left on an elevated bundt pan. After the marbles had collected a layer of dust, they were rinsed with distilled water and that water was then analyzed.

Up to 45% of the dust at the highest elevations in Yosemite was from Asian sources, said UC Merced graduate student Nicholas Dove, who worked on the study. Study authors said they were able to identify the dust’s region of origin by analyzing its chemistry, geologic age and isotopic content.

Sand storms in the Gobi Desert lift the dust into the sky, where it is carried thousands of miles over the Pacific Ocean for several days, according to Dove. When it reaches the United States, the air carrying it is squeezed like a dirty sponge against California’s mountains, and the dust is deposited along with rain or snow.

“People have known that’s occurring for quite a while, they just didn’t know how important it was to the ecosystem,” said Bales.

ALSO

A wet winter makes some California hikes more treacherous than usual

A woman fights to save her rhinos armed only with her grandmother's shotgun

Hold the mustard: In Orange County land reserve, an unwelcome guest sprouts among native plants

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.