‘Brendon didn’t have to die’: Family of man fatally shot by LAPD in Venice says they’re left grieving and wondering

- Share via

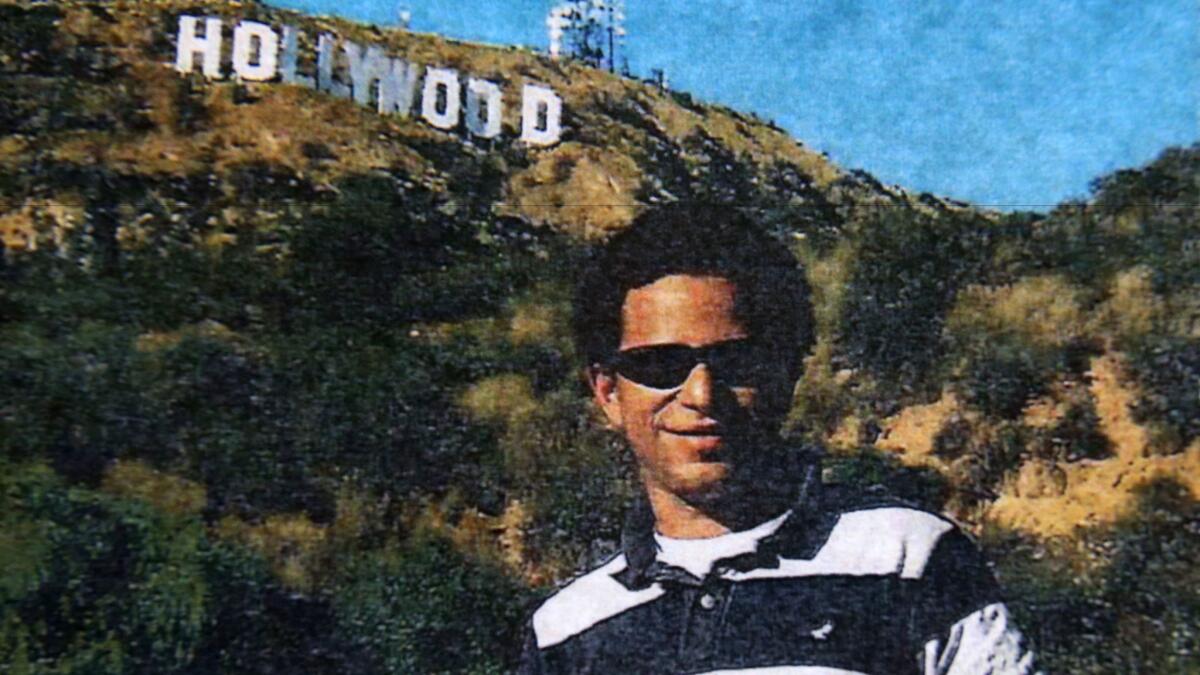

When Brendon Glenn arrived in Venice, he was quickly captivated by one of L.A.’s most memorable spots, an eclectic stretch of beach that has long attracted travelers like the 29-year-old.

The New York native was on a yearlong trip to find work and adventure in California, where he marveled at the abundant sunshine and fresh avocados. In Venice, he found people who, like him, loved to skateboard and spend time on the sand.

“There’s a really fantastic beach,” Glenn told his mother during one of their regular phone calls. “Venice Beach.”

Within days, Glenn was shot and killed by a Los Angeles police officer, stirring anger far beyond the beachside community and rekindling the long-running national debate over policing. Much of that scrutiny has focused on police shootings of black and brown men. Glenn was black, as was the officer who shot him.

Glenn’s death prompted a $4-million legal settlement with his family and a recommendation from Los Angeles Police Department Chief Charlie Beck that prosecutors charge the officer who shot him — the first time as chief that Beck has suggested criminal charges against an officer in a fatal on-duty shooting.

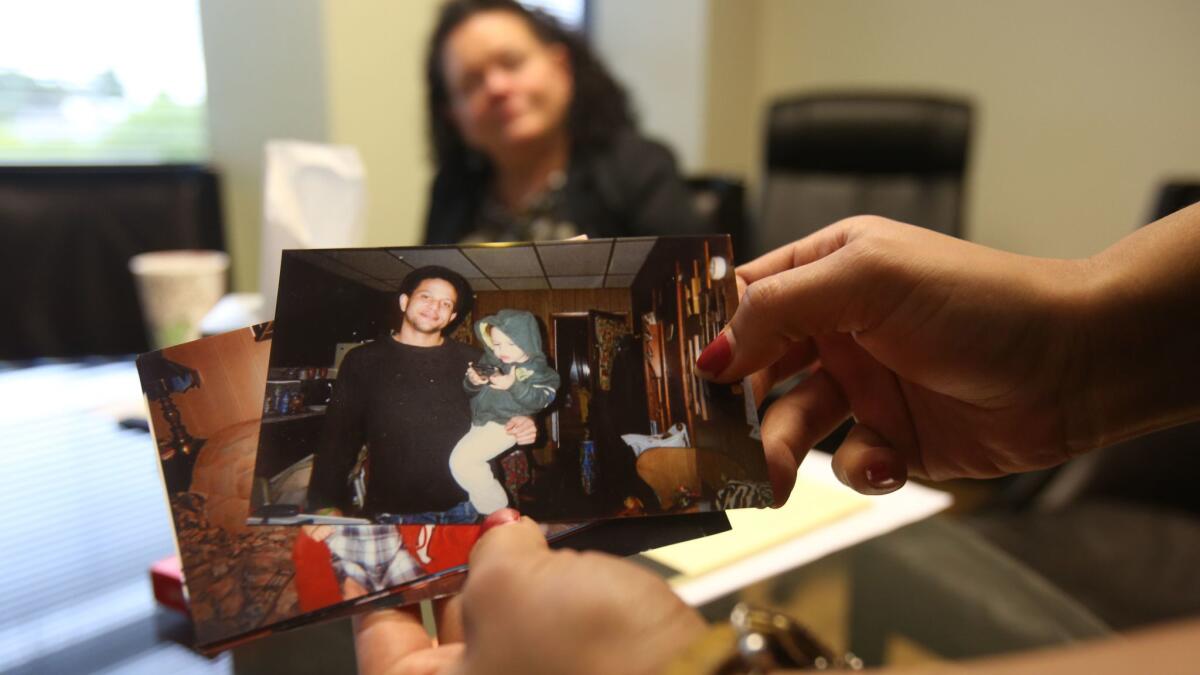

As the district attorney’s office weighs whether to prosecute, Glenn’s mother and sister describe their still-lingering disbelief that he is dead, their desire to see the officer behind bars and their frustration that Glenn is largely known, at least in Los Angeles, as little more than an unarmed homeless man shot by police.

Glenn was an adventurer who wasn’t afraid of a challenge, they said, someone who was willing to help or talk to just about anyone. He loved cracking jokes and Cinnamon Toast Crunch. He was close to his family, attending each of his younger sister’s graduation ceremonies.

“People don’t seem to know what type of an individual he was,” said Glenn’s sister, Brittany. “That hurts to the core.”

Brittany Glenn said the chief’s comments, along with the Police Commission’s decision earlier this year that the shooting was unjustified, proved that the killing was wrong. But that doesn’t change the fact that her brother is gone, she said.

“That’s the part where us, the family members, are left grieving and wondering what’s going to happen as a result of this,” she said. “What is the punishment going to be?”

The night Glenn was killed, Officer Clifford Proctor and his partner responded to a complaint that a homeless man was harassing customers outside a Windward Avenue restaurant, police said. Glenn started to walk away when they first approached, so they decided not to arrest him, according to a report from Beck that was made public this year.

Then Glenn headed to a nearby bar, where he yelled at patrons and started scuffling with a bouncer, the report said. The officers walked over, planning to take Glenn into custody.

One grabbed Glenn’s arm and told him to turn around, the report said. Glenn refused, so the officers took him to the ground.

At one point, Proctor told investigators, he saw Glenn’s hand on his partner’s holster and thought he was trying to grab the officer’s gun, according to the report. Proctor then opened fire, hitting Glenn in the back.

But security video from the bar and statements from Proctor’s partner disputed his account and did not indicate Glenn was reaching for the gun, the report said. The video has not been made public.

Proctor was relieved of duty and has not returned to work since the shooting. His attorney did not return messages seeking comment.

The shooting rattled Venice, particularly the young, homeless people whom Glenn camped with on the beach. After the shooting, as investigators combed the scene, Glenn’s friends held signs with his name outside the yellow police tape. They later packed a town hall meeting, criticizing police.

“They were scared to death,” said Timothy Pardue, who worked at a drop-in center down the street from where Glenn was shot. “They all thought it could happen to any of them.”

Glenn stopped by the center every day for about a month, Pardue said, grabbing food or fresh clothes, using the computer and getting help with his resume. Pardue was trying to help Glenn find work around the time he was killed.

That night, Glenn stopped by a meeting at the center, Pardue said. Glenn told him he had spent most of the day drinking — it was Cinco de Mayo — but soon broke down in tears, saying he missed his mother and son.

A few hours later, Pardue said, he heard the gunshots.

“They could have pepper-sprayed him. They could have tased him,” Pardue said. “They could have done anything but shoot him.”

They could have pepper-sprayed him. They could have tased him. They could have done anything but shoot him.

— Timothy Pardue, who knew Brendon Glenn through a Venice drop-in center

Though Glenn stayed on the beach, his family rejects the idea that he was homeless. He had a place to stay with a childhood friend in San Diego, they said, and a home with his tightknit family in New York. Venice was a temporary stop.

He was also the kind of person who thrived outside, they said. Glenn and his sister went to summer camp for about a decade, she said, where he rode a mountain bike up Mt. Washington — the highest peak in the Northeast. But that wasn’t enough, Brittany Glenn said. Her brother then gathered a group of boys who carved canoes out of weathered tree trunks.

“He was an adventurer at heart,” Brittany Glenn said. “He wasn’t frightened by a challenge.”

Glenn left New York for California in August 2014 to find work, his family said, encouraged by the friend who lived in San Diego. After the new year, Glenn moved to a farm outside Sacramento, where he lived and worked for about three months before he left and stopped in Venice on his way back to San Diego.

Cathy Suematsu and her partner own the farm, where Glenn pruned fruit trees, built a deck at a community building and hung sheet rock in an old homesteader’s cabin. He also helped take care of Suematsu’s young children, she said, reading them books and going on walks.

After he died, Suematsu said, people who knew him from the farm held a vigil. They also sent a letter to Beck, saying they were upset that Glenn had been killed.

“I never saw him be violent or aggressive,” Suematsu said. “I couldn’t imagine that somebody could justify killing him.”

Sheri Camprone, 60, said her son wouldn’t hesitate to help others. He shoveled their neighbors’ driveways when it snowed. He worked as a lifeguard in high school. When he was a teenager, he moved in with his ailing great-grandmother to help care for her.

After Glenn went to California, Camprone said, they would video chat every Sunday, when Glenn’s son Avery, then 3, was at her house. When he worked on the farm, Glenn had to drive a few miles just to get a signal strong enough to call.

“Make sure you listen to Gigi while I’m gone,” Glenn would say, using Avery’s name for Glenn’s mother.

Glenn had most recently been paving and repairing roads for the city of Troy, N.Y., but was looking for work when he decided to head west. It was difficult for him to leave his son and go to California, Camprone said. But he thought the state would give him the opportunities to find good work. The plan, Camprone said, was for Glenn to stay for a year, then come home to New York.

“It was tough on all of us for him to leave,” she said. “But it seemed like it was going to be a good thing for him.”

Camprone last spoke to her son a few days before his death.

“I’m coming home,” he told her. “I miss my son too much.”

“All right. Come home, hon,” she replied. “We’re here.”

Camprone and her daughter said they were hurt by what they described as a lack of response from the city after Glenn was killed. They said they haven’t heard from the Police Department about the shooting or the investigation, despite the chief’s comments to the media.

“It’s like we don’t exist,” Camprone said.

When asked about the family’s remarks, a spokesman for the LAPD said in a statement that the police chief still believes Proctor should be criminally charged over the shooting, again calling it an “unjustified use of deadly force” against Glenn.

“The LAPD is sorry for his untimely death and deeply regrets the pain his family has suffered from this profound loss,” the statement said.

The LAPD is sorry for his untimely death and deeply regrets the pain his family has suffered from this profound loss.

— LAPD statement on the fatal shooting of Brendon Glenn

Brittany Glenn is now 29, the same age her brother was when he was killed. She thinks about the moments he’ll miss — her upcoming wedding, her future children. Camprone struggles to explain her son’s death to her 4-year-old grandson, who still asks when his father is coming home.

The family left an empty chair for Brendon Glenn at the table during their Thanksgiving meal, in between his mother and sister. The tears still come without warning, they said. At Wal-Mart. Or at the grocery store.

“It’s the worst thing to go through in your life, to lose your child,” Camprone said. “Brendon didn’t have to die.”

Click here for a Spanish version of this story

Follow me on Twitter: @katemather

ALSO

Under intense pressure, D.A. Jackie Lacey faces crucial test with two high-profile police shootings

Family demands federal investigation after Bakersfield police kill 73-year-old man

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.