Garcetti faces heat over L.A.’s homeless crisis but remains optimistic. Is he being realistic?

- Share via

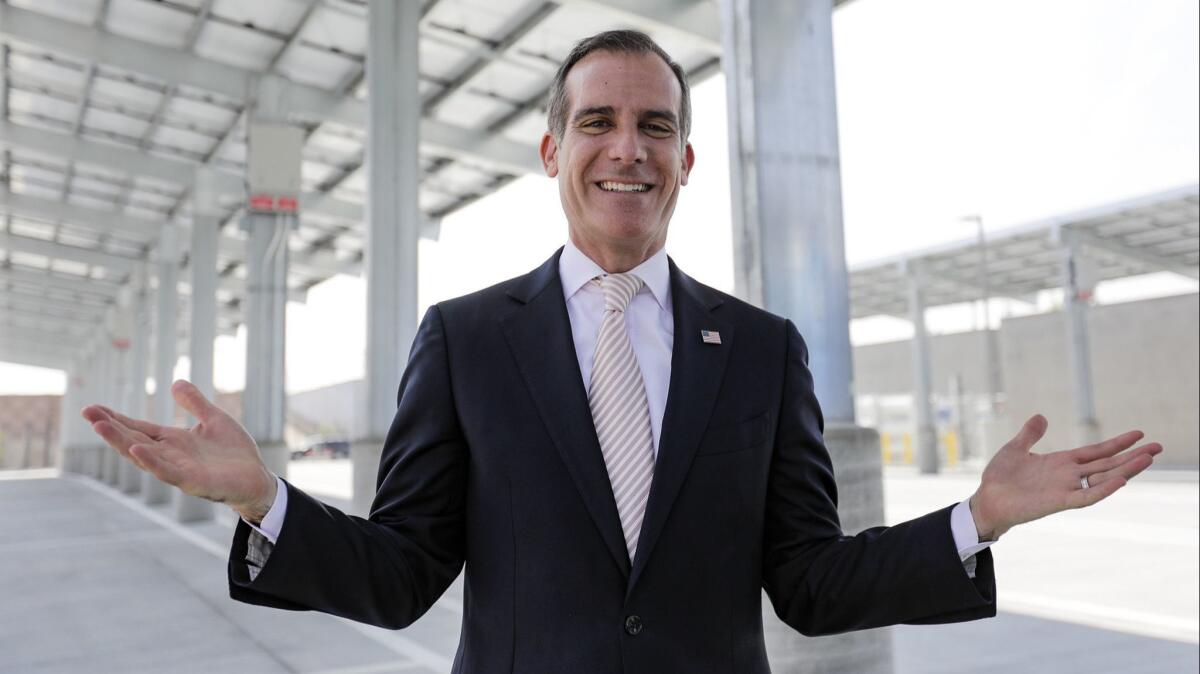

When exploring a White House run last year, Mayor Eric Garcetti pitched Los Angeles as a resurgent and diverse city that’s adding rail lines, green jobs, new museums and sports stadiums.

It’s the same optimism that still fills his Instagram account, where he shows photos of dazzling pink sunsets, construction cranes and Rams uniforms.

But many in Los Angeles see a different city, one marked by growing homelessness and filth that government leaders are struggling to address.

With three years left as mayor, and his presidential aspirations on hold, Garcetti’s reputation — and political future — could rest on his ability to bring tangible improvements to the streets of Los Angeles.

There is no question Garcetti has been a leading advocate for securing additional money to create housing and homeless services. But there is debate about whether he could be doing more and whether the mayor, known for his laid-back disposition, is treating the crisis with enough urgency.

Garcetti is “affable and likable,” said Jessica Levinson, who teaches election law at Loyola Law School, but he’s now confronting “an emergency level” problem.

“It may be that in five or 10 years, we look back and think Garcetti got us out of this mess,” she said. “But that’s not what we feel today.”

That became clear Tuesday when the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority reported that the number of people without permanent housing in the city rose 16% this year. The rise comes in spite of the hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars spent on the crisis.

“The city is going to hell in a handbasket,” said Mark Ryavec, president of the Venice Stakeholders Assn., who described recently watching a man drop his pants on a main stretch of the tourist district and urinate on the sidewalk.

Ryavec blames Garcetti and others at City Hall for policies that he says are enabling homelessness, including a recent court settlement in which the city agreed not to limit the total amount of personal property that homeless people can keep on skid row. He called the city’s approach “assisted suicide for the homeless” and wants a crackdown on quality-of-life violations.

The mayor remained steadfast about progress on homelessness by the city and county, and in an interview, he rejected the idea that Los Angeles was hitting rock bottom.

More than 20,000 people were helped into housing last year, a record number. Other cities and counties in Southern California reported bigger increases in homelessness than Los Angeles did, a sign that local policies are working, Garcetti said.

The mayor said scores of housing units and shelter beds are being added in the next few years — the result of heavy spending by the city this year. He warned that growing numbers of renters are falling into homelessness but also said he was hopeful about a turnaround in the overall crisis.

“This is the first honest year to see progress from now to next year,” Garcetti said, “when we actually see the money flowing, the machine built and people being helped off the streets.”

Tuesday’s report on homelessness in L.A. was one of a trio of recent setbacks for Garcetti. Voters also overwhelmingly rejected his proposal for a tax increase for schools, Measure EE, and the candidate and longtime aide he endorsed, Heather Repenning, lost her bid for a school board seat last month.

But it’s homelessness that’s most likely to define his legacy as mayor.

There are complex causes for the crisis, which is prevalent across the West Coast, but many blame a lack of affordable housing.

Still, California legislators this year shelved or pared down several bills that could have increased housing construction and protected renters in Los Angeles. And the Golden State’s long-standing battle with President Trump over immigration issues may not help L.A. as Garcetti calls for more federal aid for homelessness.

Garcetti was elected mayor when the city was clawing back from the Great Recession. A resurgence followed, bringing new residential towers, parks and upscale eateries, along with a flurry of regional sports teams and cultural institutions, including the Los Angeles Football Club and the Broad museum.

But the renaissance also pushed out low-income renters as wages stalled and housing prices shot up.

More than 36,000 people are homeless in Los Angeles, according to county officials.

Garcetti’s major initiatives to tackle the problem haven’t been fully tested. His plan for temporary shelters in all of the city’s 15 council districts has been stymied by neighborhood opposition, construction setbacks and inaction by some council members.

Housing units promised under Proposition HHH, the $1.2-billion bond measure passed by voters in 2016, won’t start opening until later this year. At the same time, rising costs for the projects have some politicians seeking to ditch that model in favor of less expensive options to shelter people.

Longtime homeless advocate Tanya Tull helped develop emergency shelters in Los Angeles in the 1980s. She said the mayor needs to push for more hygiene facilities.

“Get the toilets, get the showers, get the street cleaning,” Tull said. “Face the fact that the development of housing isn’t going to meet the need for decades.”

Amid reports of rats and illegal dumping, Garcetti visited downtown this week and walked by boxes of cherries and rotting papayas, he said. The city is intensifying street-based services, he said.

“I take full responsibility for keeping the city clean,” Garcetti said. “‘Back to basics’ is my mantra.”

Raphael Sonenshein, executive director of the Pat Brown Institute for Public Affairs at Cal State L.A., said people are feeling “jarred” by the rise in homelessness and cautioned a broader look at the new numbers.

“The thing is not to panic and not to abandon what’s working,” Sonenshein said. “What numbers are moving in the right direction and why?”

The slow pace of progress prompted some city leaders and activists to call this week for new, more immediate solutions.

“I don’t get the sense that our city departments have a sense of urgency about this problem,” said City Councilman Mike Bonin, who wants to look at putting homeless people into existing apartments and homes. “There’s no level of government that has responded to this in the way that L.A. responded to the Northridge earthquake. Nobody is treating this as a natural disaster.”

The long-term political implications of the crisis for Garcetti are unclear. Working Californians, a group affiliated with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power’s largest union, last week attacked Garcetti over homelessness in a television and radio campaign, saying his proposed environmental goals will make the city more expensive. The union fears job losses under Garcetti’s recently released “Green New Deal.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom faced criticism when he grappled with entrenched homelessness as San Francisco’s mayor, but he went on to higher office.

Times staff writer David Zahniser contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.