LAPD pioneered predicting crime with data. Many police don’t think it works

- Share via

The Los Angeles Police Department took a revolutionary leap in 2010 when it became one of the first to employ data technology and information about past crimes to predict future unlawful activity. Other departments around the nation soon adopted predictive policing techniques.

But the widely hailed tool the LAPD helped create has come under fire in the last 18 months, with numerous departments dumping the software because it did not help them reduce crime and essentially provided information already being gathered by officers patrolling the streets.

After three years, “we didn’t find it effective,” Palo Alto police spokeswoman Janine De la Vega said. “We didn’t get any value out of it. It didn’t help us solve crime.”

The Mountain View, Calif., Police Department spent more than $60,000 on the program between 2013 and 2018.

“We tested the software and eventually subscribed to the service for a few years, but ultimately the results were mixed and we discontinued the service in June 2018,” spokeswoman Katie Nelson said in a statement.

The program was designed to predict where and when crimes were likely to occur over the next 12 hours. The software’s algorithm examines 10 years of data, including the types of crimes and the dates, times and locations where they occurred.

Beyond concerns from law enforcement, the data-driven programs are also under increasing scrutiny by privacy and civil liberties groups, which say the tactics result in heavier policing of black and Latino communities.

In March, the LAPD’s own internal audit concluded there were insufficient data to determine if the PredPol software — developed by a UCLA professor in conjunction with the LAPD — helped to reduce crime. LAPD Inspector General Mark Smith said there also were problems with a component of the program used to pinpoint the locations of some property crimes.

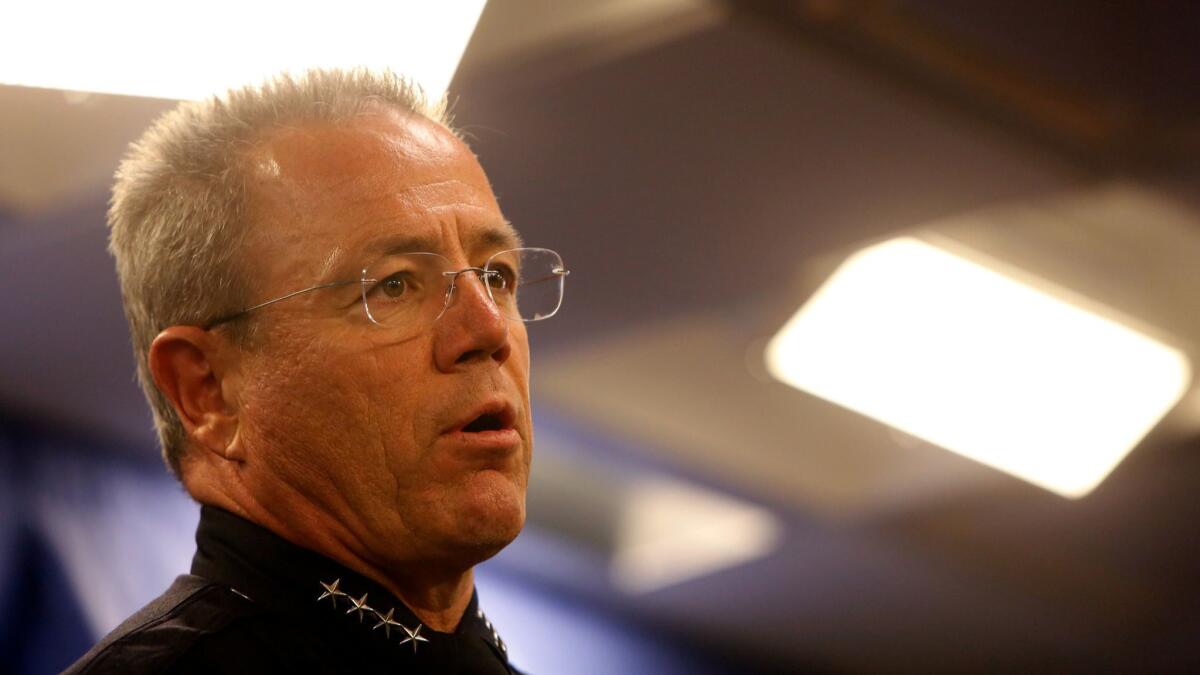

In response, Los Angeles Police Chief Michel Moore ended a controversial program intended to identify individuals most likely to commit violent crimes and announced he would modify others.

But Moore defended the PredPol software, saying it augmented the department’s efforts to target property crimes and was more accurate than human analysts at pinpointing potential hot spots.

“I believe in it,” Moore said. “I believe in location-based strategies.”

PredPol Chief Executive Brian MacDonald said the software was never intended to be the solution to reducing and preventing crime.

“We present them with a set of tools,” he said. “It’s virtually impossible to pinpoint a decline or rise in crime to one thing. I’d be more surprised and suspicious if the inspector general found PredPol reduced crime.”

Lowered expectations

Some police leaders and academics expected predictive technology to revolutionize law enforcement by preempting criminal activity.

That didn’t happen.

In Rio Rancho, N.M. — a city of about 100,000 spread over 100 square miles — Police Capt. Andrew Rodriguez said PredPol was a disappointment.

For example, he said, it targeted a remote desert area as a hot zone for cars being stolen after thieves dumped one vehicle there. The department ultimately dropped the service.

“It never panned out,” said Rodriguez, who spent 11 years with the LAPD. “It didn’t really make much sense to us. It wasn’t telling us anything we didn’t know.”

Currently, 60 of the roughly 18,000 police departments across the United States use PredPol, MacDonald said, and most of those are smaller agencies with between 100 and 200 officers.

The company warns departments that the software might not produce meaningful results if the volume of crime being tracked isn’t sufficient or if patrol cars can’t be tracked with GPS devices. It is up to local law enforcement, MacDonald said, to determine how using data will best help them.

“Having all your officers on the same page really makes a difference,” MacDonald said, comparing it to a gym membership. “You have to use it for it to work,” he said. “It’s driven by how the agency is run.”

UCLA anthropology professor P. Jeffrey Brantingham, who helped develop the software and co-founded the company, said the technology behind the program — data-crunching and geo-mapping — is sound.

“The science is clear in how it drives predictions,” he said.

The Hagerstown, Md., Police Department canceled its $15,000-a-year software service in 2018 because of budget constraints, Chief Paul Kifer said.

Although a study commissioned by the department found that crimes reported at a police station had skewed the data and predictions, it also “couldn’t show that it didn’t work.” he said. The study also found no racial bias when officers targeted location-based crimes, he said.

Kifer hopes to restore the service at some point.

“It was a tool,” he said. “There was nothing absolute about it. It added value for us.”

And some agencies are still investing in the data program: Police in Birmingham, Ala., recently spent $60,000 on PredPol, touting its potential to help reduce crime. Police Chief Patrick D. Smith, a retired LAPD commander, and the mayor’s office did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

MacDonald acknowledged that the company tells prospective buyers the LAPD uses the software, but he said he doesn’t believe it has helped make any sales.

While other departments have spent money on the software, the LAPD made its first payment — $50,000 — this year for server maintenance, he said.

How it works in L.A.

Hours before officers hit the streets in the LAPD’s 21 divisions, crime analysts and division leaders discuss potential hot spots.

Each day the PredPol program generates 10 “boxes,” about 500 feet by 500 feet each, designated as zones for possible property crimes such as burglaries and car thefts.

Officers are expected to patrol the areas when time allows during their shifts; the GPS system in patrol cars allows their movements to be tracked.

The department recently began posting the maps online and sharing them on social media — publicity that in itself may serve to deter crime.

West Valley Division crime and intelligence analyst Sara Pilgreen posts the maps and answers questions on social media. At first, she said, she needed to explain to residents what the maps represented. Residents, she said, are now sharing them for others to see.

“There’s a lot of moving parts to this,” Pilgreen said. “This gives the public a better understanding.”

Capt. Steven Embrich, commanding officer of the West Valley Patrol Division, said that PredPol puts police in certain neighborhoods every day — adding that specialized units also target the areas.

“When there is a lull in action, you are expected to be in the areas,” Embrich said of officers. “We’re targeting where the crime is. It’s paying off for us. Their presence is a deterrence to crime.”

On a recent daytime patrol, Senior Lead Officers Denise Vasquez and Oscar Bocanegra headed south of Ventura Boulevard to neighborhoods highlighted for potential burglaries.

Vasquez noticed several homes being renovated. Trucks filled with tools and supplies sat in driveways.

“What is making crime go up in the box?” Bocanegra said, explaining that patrol officers are on the lookout for factors that might influence criminal activity in a neighborhood.

As the duo cruised through residential areas, they scanned yards between houses and alleys for suspicious activity.

They also look for vehicles with no license plates, Bocanegra said.

On commercial corridors, officers also walk the streets to talk to business owners about what could be driving up crime. In the West Valley Division, burglaries and motor vehicle thefts rose 3% and 9%, respectively, from April to May, records show.

Addressing criticism of bias, Vasquez pointed to the daily mission sheet listing only addresses, not information on individuals.

“It’s about being in the right place at the right time,” Vasquez said. “We still need probable cause. We’re not violating any rules or laws.”

Alex Garay, president of the Encino Neighborhood Council, said residents like that police use the prediction software and other tools to fight crime.

“It’s very, very valuable to have police in a high-crime area,” he said. “If it gets them in certain areas between answering calls, it helps. The visibility absolutely helps.”

Assessing the impact

But the use of complicated algorithms for data-driven programs like PredPol makes it difficult to evaluate their overall effectiveness in targeting crime. Since the programs forecast risk, much of their efficacy is in crimes never committed, some police officials argue.

The Los Angeles Police Commission, the civilian panel that oversees the department, has called for a greater accounting of the programs and specifics on how future results would be measured and made public.

The commissioners also wanted to know how police will monitor against overly aggressive policing of communities of color.

Changes already underway include developing “smaller micro hot spots” and removing crimes reported by people at police stations.

The Stop LAPD Spying Coalition has long criticized the department’s data tools, arguing that the information collected is inherently biased because poor, black and brown communities are targeted more for crime suppression.

“One of the largest police departments in the country has been using PredPol for almost a decade in ways that its own inspector general couldn’t even audit the program,” said a statement from Hamid Khan and Jamie Garcia, two of the group’s leaders.

“This discovery should call into question all studies done about PredPol and if the data used in these studies was even accurate.”

The Los Angeles Police Protective League disagrees.

Predpol and other data programs are far from perfect, but they are a tool police should use to help keep residents safe, said LAPD Officer Steve Gordon, a union director.

“Professional activists want zero proactive policing in neighborhoods impacted by crime and slap-on-the-wrist punishments for those who do get arrested,” Gordon said. “We want to put our resources where we know we can make a neighborhood safer by targeting actual crime and behavior.”

Moore, along with Brantingham and MacDonald, reiterated that the algorithm excludes racial identifiers. The chief told The Times the department “recognizes the criticism” surrounding PredPol and he pledged to provide more updates to the public and commission.

He also said he was seeking an independent study of the data program to determine if it needs further adjustments.

Meanwhile, publicizing the crime maps will allow residents to make their homes, vehicles and neighborhoods safer, he said.

He encouraged Angelenos to check whether their neighborhood shows up in a hot zone. He compared PredPol to a patrol car that sits near an intersection to change the behavior of speeding motorists.

“It has a deterrent effect on individuals who may see an opportunity to prey upon a car or home,” he said.

But John Hollywood, a senior researcher and professor at Rand Corp., said predictive policing has not revolutionized law enforcement.

Police departments, he said, don’t need a computer to tell them crime will drop if more officers target an area. The prediction programs, he said, are mapping tools and do little to decrease crime.

“The effect is very small,” Hollywood said. “It can be hard to see.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.