L.A. teachers’ strike brings day of disruption for thousands of students

- Share via

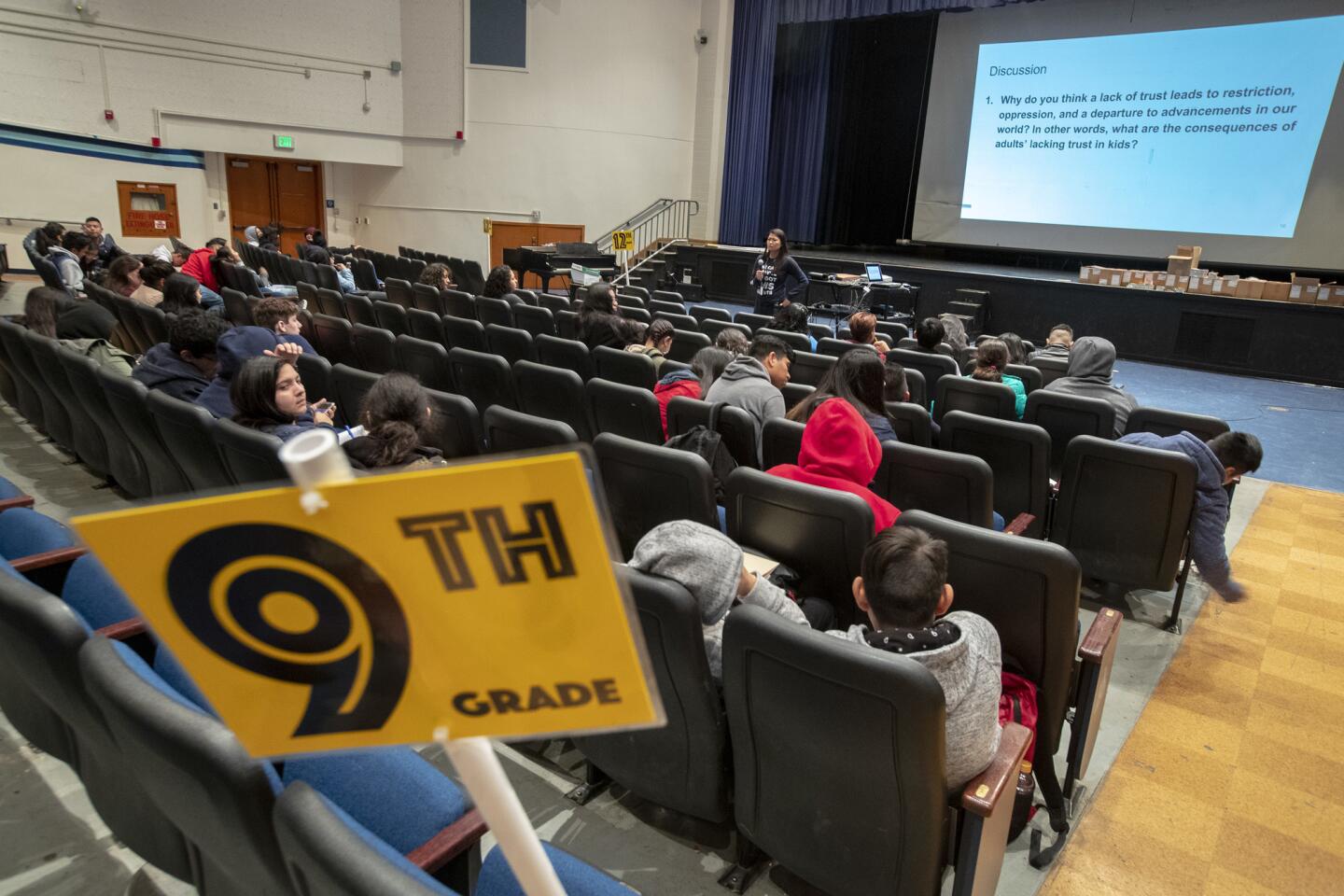

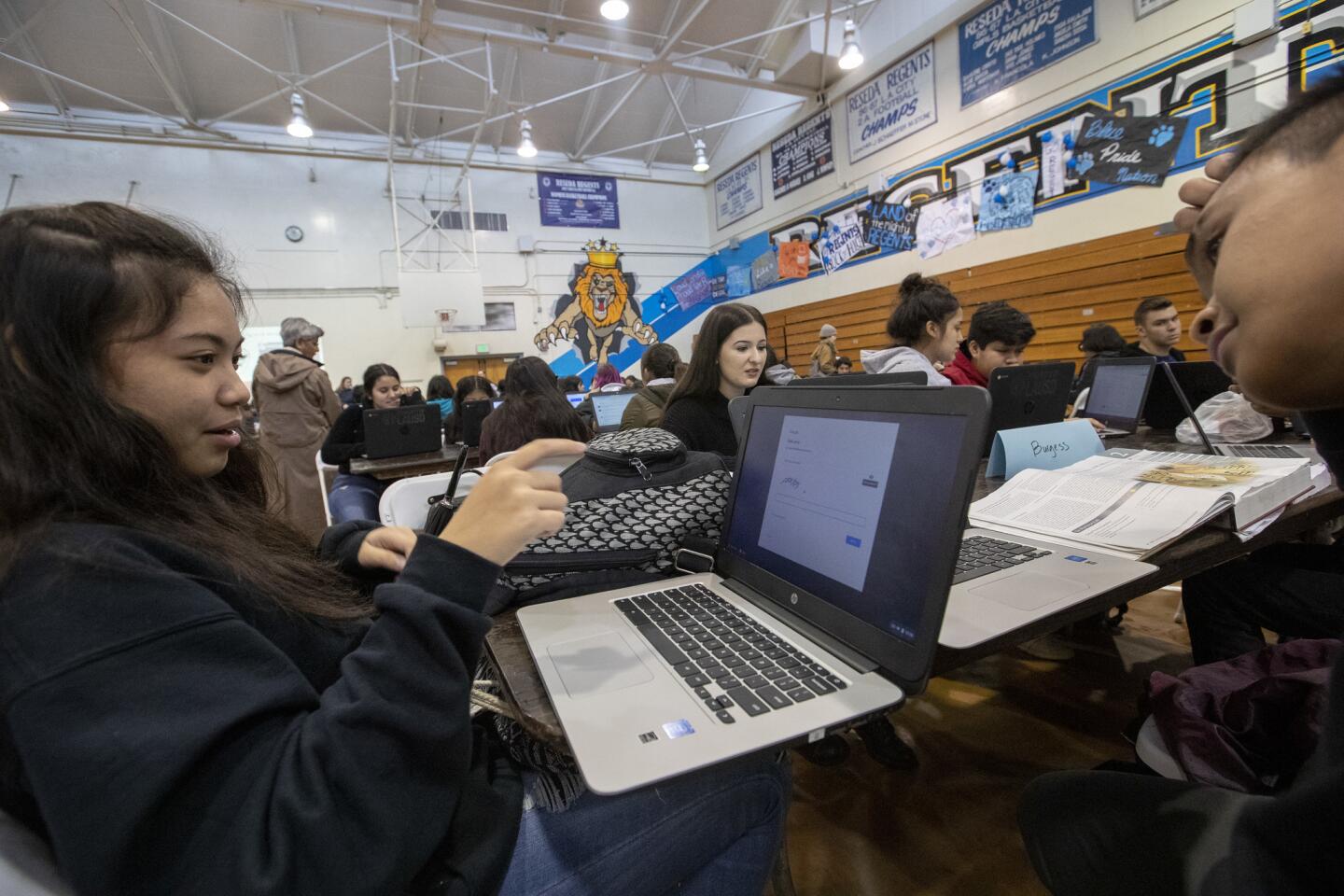

Across a rain-drenched city, students crowded into school auditoriums, talked over the adults brought in to manage them, watched “Black Panther” and played “Minecraft.”

From San Pedro to El Sereno to Reseda on Monday, skeletal staffs crammed students together to try supervising them as Los Angeles teachers went on strike for the first time in 30 years.

The walkout of 31,000 teachers union members proved to be the massive disruption hundreds of thousands of students and their families had feared. The vast majority of the district’s parents and guardians are low income, and many had to choose between missing work to watch their children or sending them into an unknown situation at school. While campuses remained open, the few adults present struggled to keep students engaged.

Only low attendance prevented an even more chaotic scenario of adults managing hundreds of students each. At the end of the day, the district reported that about a third of its students had shown up.

Inside the auditorium of Sherman Oaks Center for Enriched Studies in Tarzana, Assistant Principal William Crockett called a group of high school students to order.

He gave them instructions: Turn off Wi-Fi on all personal devices. Speak in whispers.

They were handed Chromebook laptops to do online lessons.

“The last rule is a very simple one,” Crockett said. “Don’t be a jerk.”

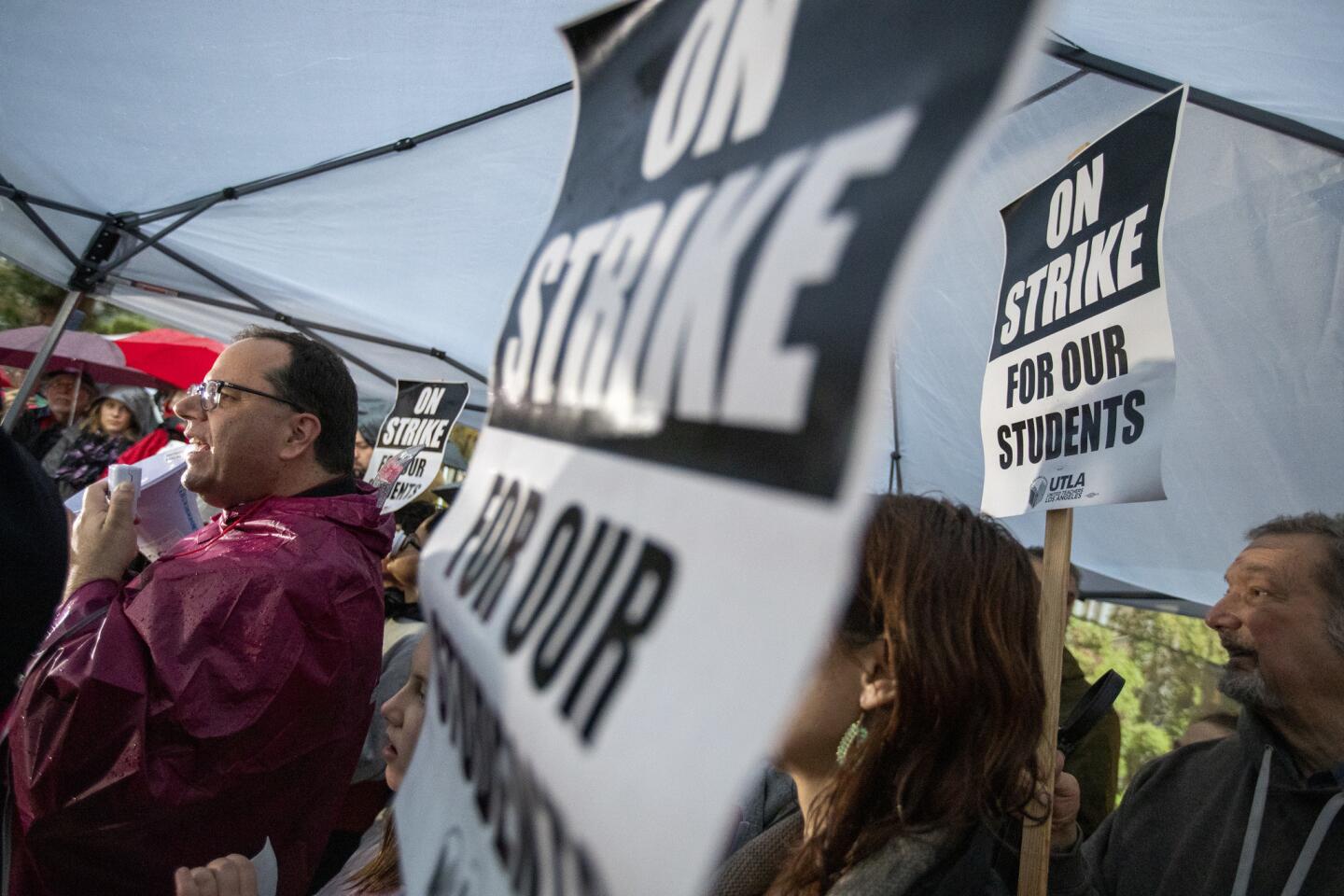

Negotiations between United Teachers Los Angeles and nation’s second-largest school district broke off late Friday after more than 20 months of bargaining, with no resolution to the educators’ demands for smaller class sizes, better pay and more support staff.

Supt. Austin Beutner called for an end to the strike during a news conference Monday morning and said the district remains “committed to resolve the contract negotiations as soon as possible.” He repeated his assertion that the district simply does not have the money to meet the teachers’ demands and urged the union to return to the bargaining table.

UTLA would not budge, saying the latest offer to reduce class-size guaranteed better staffing only for one year.

“Let’s be clear, educators don’t want to strike,” union President Alex Caputo-Pearl said to a crowd of supporters during a morning news conference at John Marshall High School in Los Feliz. “We don’t want to miss time with our students. We don’t want to have less money for the car payment or less money for the school supplies that we always end up buying ourselves.”

Mayor Eric Garcetti said he expected the two sides to get back together no later than the beginning of next week. He said high-level representatives from both sides were talking and their positions had gotten closer.

“This is the time to make an agreement,” Garcetti said. “There is not much that separates the two sides. There has been movement toward what the teachers have demanded and what the district can afford.”

He praised the teachers’ “righteous cause.”

He also said he had spoken to Gov. Gavin Newsom, who expressed a willingness to help.

Newsom, who said he is in contact with both sides, called on them to reach a deal.

“I strongly urge all parties to go back to the negotiating table and find an immediate path forward that puts kids back into classrooms and provides parents certainty,” he said in a statement.

Negotiations are not expected to resume until Tuesday night at the earliest.

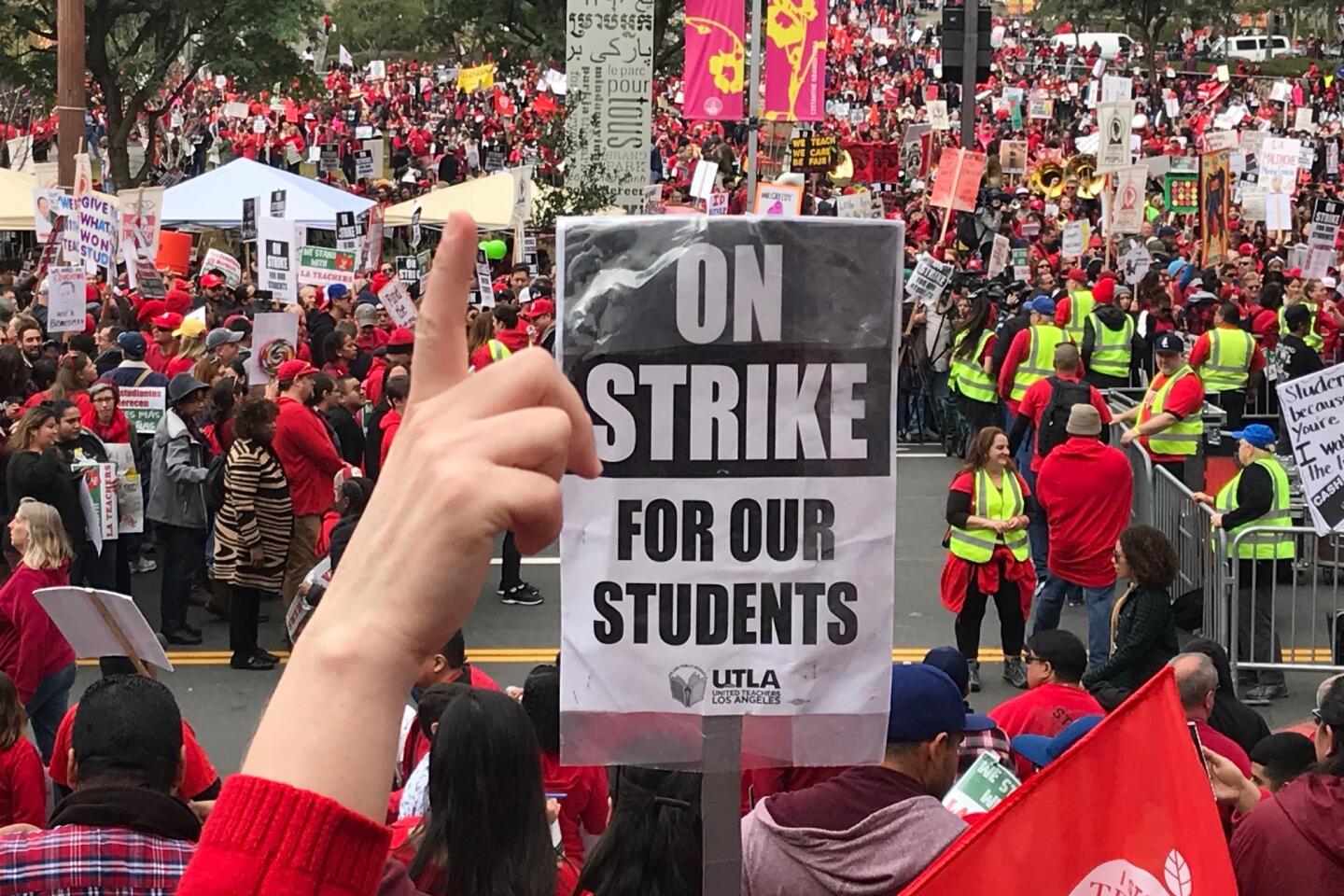

On Monday, thousands of teachers and other union members started picketing in front of their schools before sunrise. Many then joined a mid-morning downtown rally at Grand Park along with students and parents, before marching roughly a mile to school district headquarters. The Los Angeles Police Department estimated the crowd at 20,000.

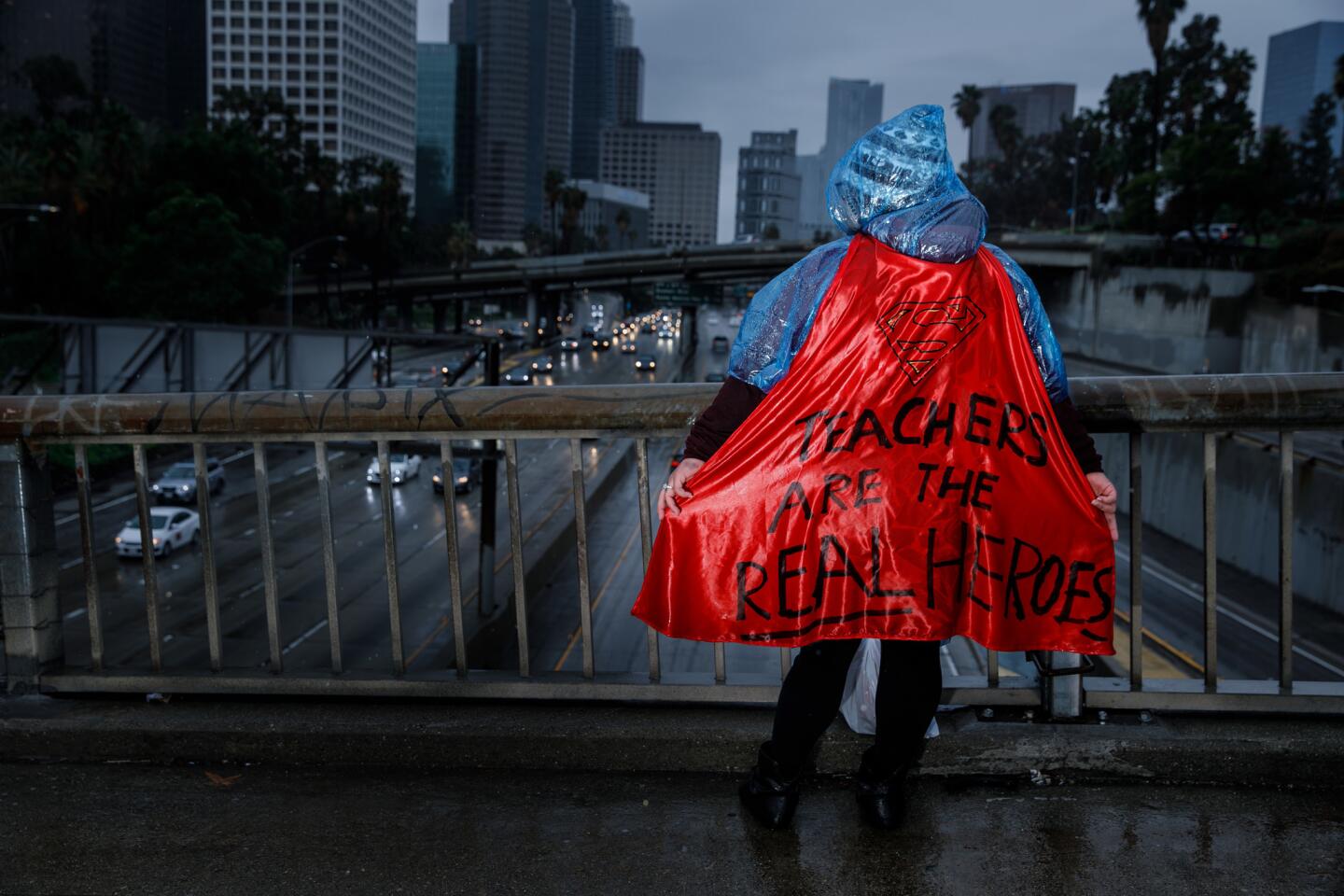

Michael La Mont, 48, who teaches third grade at Hooper Elementary in South Los Angeles, said the march represented the unity of teachers working for better conditions.

“We’re marching for the future of public education,” he said. “No one’s doing this for fun. We’re missing our kids. It’s raining. We’re not going to get paid.”

Schyler Marvin, 17, said she had 41 classmates in her AP chemistry lab at Venice High — so many that some didn’t have seats and they couldn’t complete all the labs they were assigned. And the crowding created unsafe conditions.

“People tripped over cords and sent hot plates and beakers flying,” she said.

She and five friends, all seniors, picketed with their teachers outside their school and then took the Expo Line to the downtown march. Alyssa Berman said their school’s lone college counselor was so busy that “you have to sprint” to her office at lunch or break to get a moment with her.

They said their teachers doled out weeks’ worth of homework to do in case the strike did not end quickly.

“We just love our teachers,” Justin Delgado said. “They deserve more than what they get.”

Even with the low turnout, administrators had to improvise ways to engage those who showed up.

In Koreatown, Principal Susan Canjura of the Los Angeles High School of the Arts was planning the day on the fly.

First she parked her school’s students in the auditorium to watch “Black Panther” as she scrambled to figure out what to do next. She had hoped to move them into a few classrooms to do coursework on computers. But the 15 non-teaching staff members who would normally be on hand to help walked out too, as a gesture of solidarity with the teachers union.

Luckily, two substitute teachers showed up. They handed out worksheets about the characters and themes of the movie, and got the students into classrooms.

“Some students complained that lunch was awful,” said Janet Tovar, a retired administrator who helps at the school. “They were not particularly happy campers.”

Movies appeared to be a staple of the day at various campuses. At the Ambassador School of Global Leadership, it was “Gravity,” with no post-viewing discussion.

Many parents opted to keep their children at home, sensing that otherwise they’d simply be warehoused for the day.

In the admissions office of Reseda High School, Glenda Baltazar, 33, waited for her son Diego, 14. After witnessing the disorderly scene at her other child’s elementary school, she worried about Diego because most students at his school are older than him.

When Diego came out, he told his mother the scene inside the auditorium had been chaotic. “I couldn’t get out,” he said. “There were backpacks all over the place and students were screaming and running around.”

Mari Enyart, 42, figured her 7-year-old would have sat in a cafeteria with other students at Broadway Elementary in Venice, watching a movie, perhaps reading a book.

Instead, she holed up with him at a Starbucks in Gardena near his brother’s preschool, helping him read a Japanese nursery rhyme.

“I felt it was better to homeschool him,” she said.

She knew that as a stay-at-home mom, she was lucky to be able to do so.

Enyart said she supports the teachers’ strike and suspects the district has the money to provide more staffing. She believes the district needs smaller classrooms and more nurses and librarians.

Her son’s school has no nurse or librarian, she said.

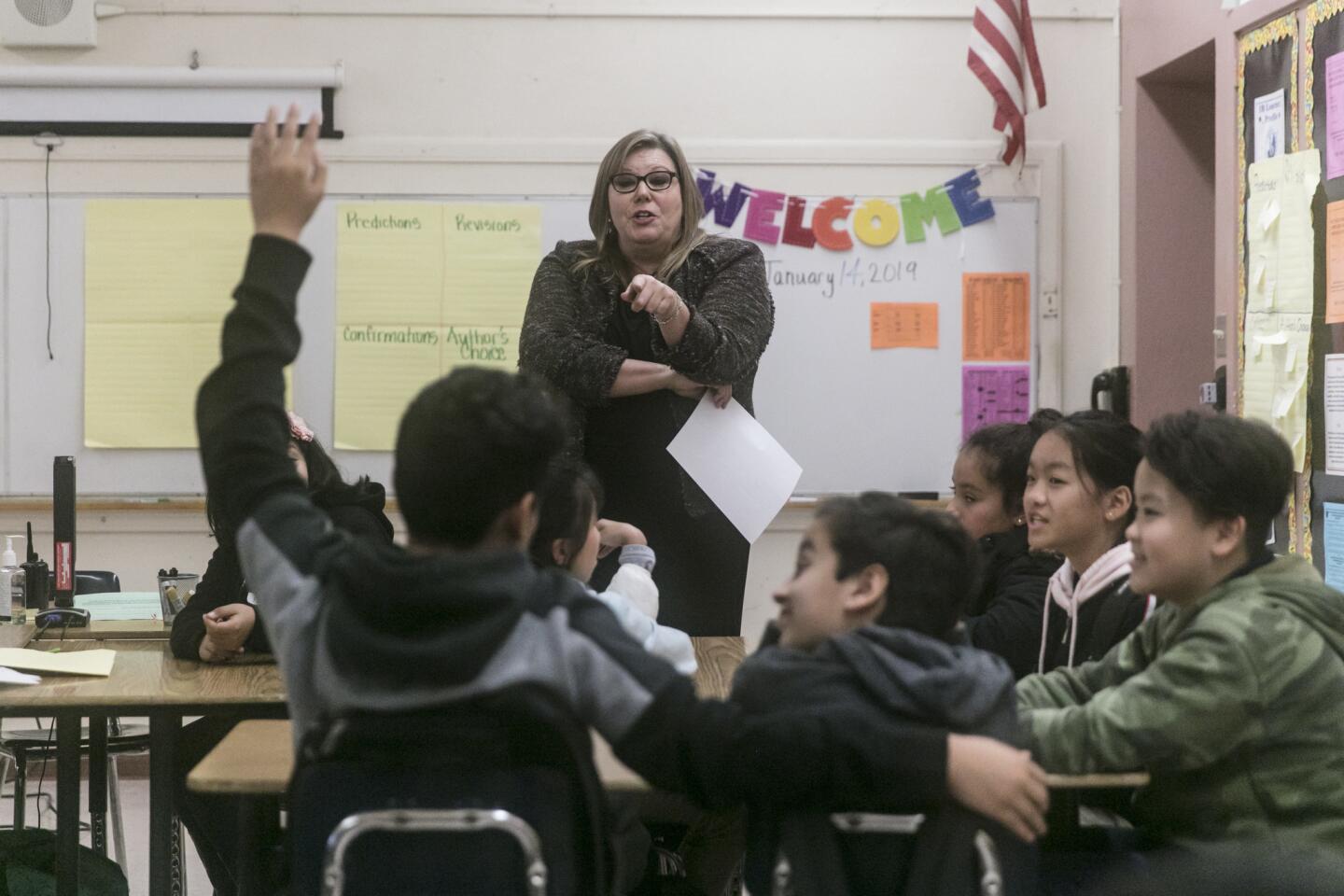

Many teachers voiced similar complaints.

Veronica Metz, a first-grade teacher at 99th Street Elementary in South Los Angeles, said the focus of the strike is less about pay and more about what students need. Her two sons attend the school, where a nurse is part time and parents volunteer to keep the library open.

“We have a nurse that only comes here on Mondays and Wednesdays,” she said. “So if there’s an emergency, hopefully it only happens on Mondays and Wednesdays.”

She and dozens of other teachers and supporters marched under umbrellas along Century Boulevard.

Juan Urquieta, a fifth-grade teacher at the same school, said that it’s difficult to give enough attention to students when the class size tops 30, and teachers increasingly spend time doing tasks that counselors should be there to do. When a child is absent, it’s on him to call home and find out why.

“We’re counselors, we’re attendance counselors, we’re teachers, and we have these large group of students,” he said. “There’s only so much we can do to help our kids.”

Laleda Hines dreaded Monday morning. She approached picketing teachers to drop her 11-year-old daughter off to catch her school bus. Then she had to cross the picket line to serve food at Manchester Avenue Elementary.

She had only had the district food service job for a year, and the labor action made her nervous about her employment, although she supported the teachers.

She believes they deserve better but is conflicted because the school district says meeting their demands would lead to insolvency.

“If the district has no money,” she said, “then there’s no job for me.”

Times staff writers Joe Mozingo, Alexa Diaz, Melissa Gomez, Suhauna Hussain, Corina Knoll, Jackeline Luna, Sam Omar-Hall, Dorany Pineda, Joel Rubin, Nicole Santa Cruz and Phil Willon contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.