The 7.1 earthquake could have been so much worse. Here’s why

- Share via

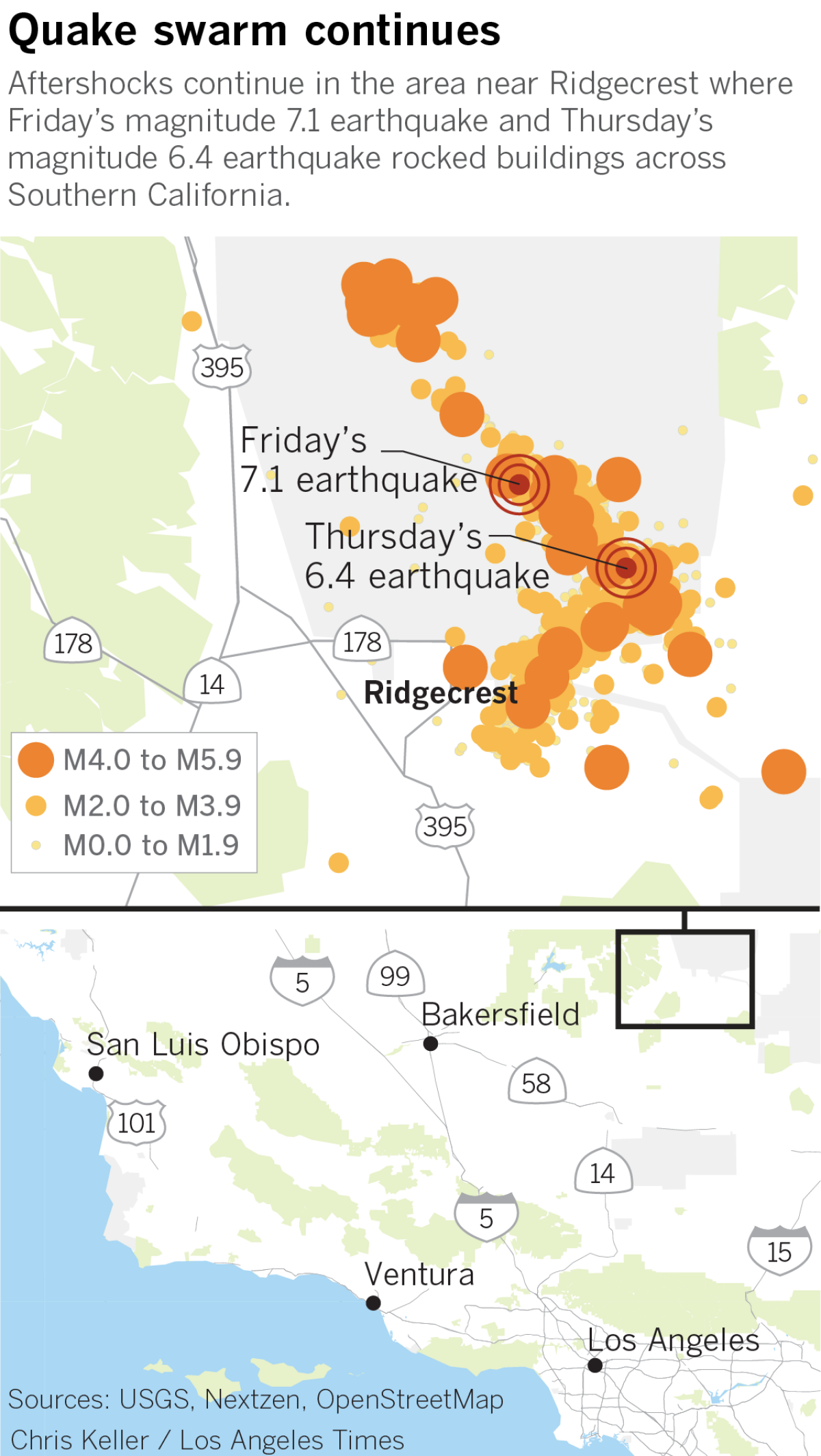

The 7.1 earthquake that hit the Ridgecrest area last week was the largest in Southern California in 20 years.

It created surface ruptures and damage near the epicenter. But experts said the quake could have been much more punishing — and could have caused more damage in the metro Los Angeles area.

“We’re very lucky there and happy there wasn’t anything worse,” said Mark Ghilarducci, director of the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services.

Moving north, not south

Friday night’s quake occurred on the same fault system as Thursday’s magnitude 6.4 temblor, with a depth of more than eight miles, Caltech seismologist Egill Hauksson said. The fault line is now about 30 miles long, he said.

The earthquake ruptured about 20 miles to the north of the July 4 earthquake.

If the energy from the earthquakes were heading south, Hauksson said, it would be “more likely to have damage to Palmdale or closer to downtown L.A.”

Full coverage: 2nd major quake in two days hits Southern California »

It has been about two decades since residents of the Searles Valley felt such a major earthquake. A magnitude 5.8 quake rocked Ridgecrest, home to about 30,000 people, in 1995. A 7.1 quake struck the Hector Mine area of the Mojave Desert about 100 miles to the southeast in 1999.

But the high desert area once saw so many temblors that it was known as the earthquake capital of the world, Hauksson said.

“This area is quite active, and has been quite active since we’ve had records,” Hauksson said Saturday.

PHOTOS: Second earthquake in two days rocks Southern California »

Lessening danger

In Ridgecrest and the surrounding areas, the tremors have subsided. Officials don’t expect any of the expected aftershocks to cause serious damage.

“The dangerous side of the hazard is tapering off,” said Cynthia Pridmore from the California Geological Survey. “Over time, these aftershocks can be fewer.”

There have been thousands of smaller aftershocks in the Searles Valley, the strongest a magnitude 4.5 quake, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. But none has caused any more surface ruptures, the California Geological Survey said. More than 45 researchers — engineers, geologists and others — met Saturday night in Ridgecrest to discuss seismological findings, the state agency said.

At least four more researchers arrived Sunday to study the ground near Ridgecrest and Trona, Pridmore said.

Geologist teams from USGS and CGS have been invited to survey the area at the Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake in Ridgecrest, near the epicenter.

Researchers are still trying to map how long the surface rupture from Friday’s magnitude 7.1 quake measures.

“One of the goals … is to see just how far north the extension of the rupture is,” Pridmore said.

Unusual pattern

Seismologist Lucy Jones says that since officials began measuring earthquakes in 1932, there have been 22 temblors of magnitude 6 or greater. Only two of those — including the one on July 4 — have been a foreshock to a larger quake.

The last was in 1987, when a magnitude 6.2 quake struck south of the Salton Sea, followed by a magnitude 6.6 earthquake 12 hours later.

Assessing the damage

“It’s moved everything 3 feet to the right,” said Martin Hudson, 52, an engineer who is part of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, an organization based in Oakland that brought researchers together in Ridgecrest to study the effects of the quakes and gave them a platform to share their findings. He was standing on one of the fault ruptures caused by Friday’s quake, which ran straight through Highway 178.

But this was just a pit stop: Their goal was to study the structural damage of the buildings in Trona so they could understand how the earthquakes affected the buildings and surrounding areas. These findings, they hope, could someday be published in a research paper and help guide future geologists and engineers.

After admiring the fault rupture, the researchers hopped in their car and headed to Trona, about 30 miles northeast of Ridgecrest. At the side of a faded pink house there, the researchers noted that soil liquefaction — some of the ground had started turning into a liquid state — had caused portions of the ground to crack and collapse. Nearby, a chimney had caved in on one of the houses.

“We saw a lot of this type of damage in the ’94 Northridge earthquake,” said Kenneth O’Dell, 55, a structural engineer.

It was hard to tell which buildings were old and abandoned and which were severely damaged by the quake. “Some of this damage was already here,” O’Dell said, noting that most of the structures were built during the 1930s and 1940s. “It makes sense that they weren’t ready for this kind of shaking. Still, the damage is not as bad as we expected.”

But the earthquake hit Trona hard, particularly because the walls of most buildings were not reinforced with steel or other material that could keep them upright or prevent cracking during severe tremors. In the end, the scientists anticipate their research could help prevent future building damage during earthquakes.

“The goal of our research is to improve the designs of these structures so that they are not as susceptible, and we’re hoping that our work today can contribute to that,” Hudson said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.