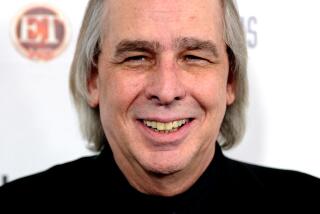

Dan Ingram, early âTop 40â DJ known for biting humor, dies at 83

Dan Ingram, one of the first and wittiest of the Top-40 radio DJs who succeeded by savaging his own medium, died June 24 at his home in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. He was 83.

He died after choking on a piece of steak, son Christopher Ingram said.

In New York and St. Louis and a slew of smaller markets, Ingram turned the playing of hit records into a daily opportunity to make fun of nearly everything, including the music he played, the ads that paid the bills and radio itself.

His show, heard on New York Cityâs WABC from 1961 to 1982, was a Mad magazine of the airwaves, and his rapid-fire thumbing of his nose at all forms of authority inspired the work of other ironists, such as David Letterman, Keith Olbermann and Don Imus.

He was a verbal machine-gun of puns and punchlines, most of them delivered in the seconds between a songâs beginning and its first lyrics. If you didnât like one line, the next was two minutes and 45 seconds away. He replied to Jimmy Ruffinâs classic âWhat Becomes of the Brokenheartedâ: âThey bleed to death.â He introduced the Chordsâ âSh-Boomâ: âAnd now, the song of the exploding librarian.â

Michael Harrison, publisher of the radio trade publication Talkers, said in a statement that Ingram was âthe greatest Top 40 radio disc jockey of all time â not just being a master of compacted content delivered by an awesome voice with a remarkable range, but a genius practitioner of timing. He raised the presentation of pop radio to an art form.â

Ingram reigned as one of the most influential and popular DJs beginning in the early years of the format, when transistor radios first made it possible to carry your music around with you on the streets, at school and at the beach. âI literally was in their ears,â Ingram said.

He sensed and fostered an intimate connection to his listeners, and developed an on-air persona that made his audience feel they were part of an inside group.

On WABC, which had a powerhouse signal that reached most of the eastern half of the country at night, Ingram called his listeners âKemosabe,â Tontoâs affectionate moniker for the Lone Ranger on the radio and TV series of that name. He was the last DJ on WABC on the day it switched from Top 40 music to political talk in 1982.

In this authorâs 2007 book, âSomething in the Air,â radio poet Ken Nordine said Ingram delivered his bits so quickly that listeners could believe they were the only ones who got the joke. Nordine found himself calling friends to ask, âDid you catch what Ingram said?â

He proclaimed a Word of the Day (âSolid!â âHumdinger!â âRococo!â) and an Honor Group of the Day (âvacuum cleaner repairmen,â âcops on the beat.â) He jabbed constantly at the tired old format that he worked in for more than five decades. âTwenty-two before three on the Ingram Travesty,â he announced one afternoon in 1962, âthe program designed to belt the Establishment.â

Some days, he dubbed his show the âIngram Atrocity;â more often, it was the âIngram Mess,â and always, he found ways to needle the powers that were.

After the news bulletin announcing the resignation of President Nixon, Ingram played Rod Stewartâs âReason to Believe,â which featured the lyric âyou lied straight-faced while I cried.â

Daniel Trombley Ingram was born in Oceanside, on Long Island, on Sept. 7, 1934. His parents were musicians, he in big bands and she in classical chamber groups. Ingram knew from childhood that he wanted to be on the radio. He attended Hofstra College (now Hofstra University) but left to launch his DJ career, spinning records at stations in New Rochelle and Patchogue, N.Y., and New Haven and Bridgeport, Conn., sometimes under his own name and sometimes as âRay Taylor.â

He figured out his act and found success at stations in Dallas and St. Louis before arriving in New York in 1961. For a few years, while he handled the afternoon shift on WABC, he also conducted a jazz and blues show, âThe Other Dan Ingram,â on the companyâs FM station.

After WABC dropped its music format, Ingram continued working in New York radio at WKTU and then WCBS-FM, an oldies station where he worked from 1991 to 2003, when he retired. He was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2007.

Survivors include his wife, Maureen Donnelly; five sons; four daughters; two stepdaughters; 26 grandchildren; and 12 great-grandchildren.

Fisher writes for the Washington Post.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.