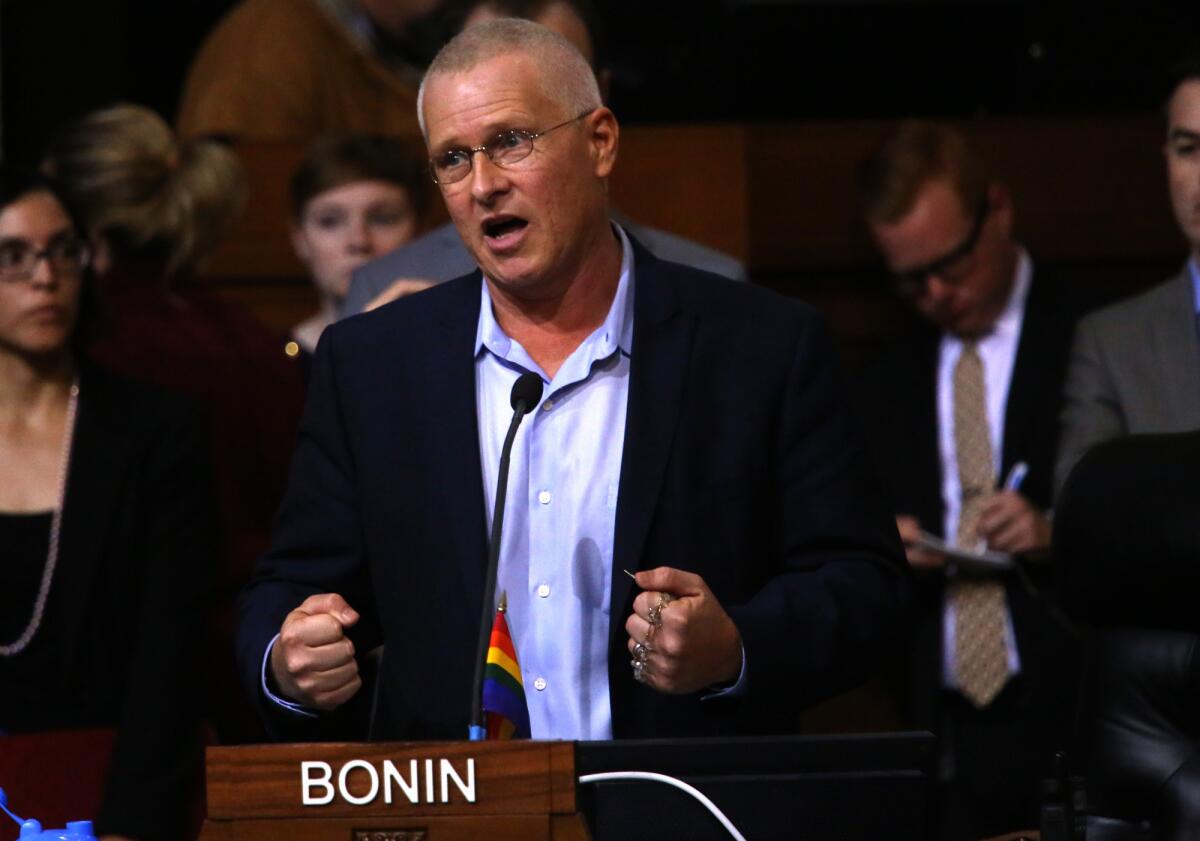

L.A. Councilman Mike Bonin proposes full public funding for city campaigns

- Share via

A Los Angeles lawmaker called Monday for the city to move to a public financing system for local elections, saying it would help address fears that wealthy donors buy influence at City Hall.

Councilman Mike Bonin said he wants voters to consider a proposal next year that would allow candidates to rely on taxpayer money rather than private contributions to fund their campaigns.

Under the voluntary system, candidates seeking public funding would have to gather a minimum number of small donations from their constituents to show that their campaigns are viable, then forgo any further fundraising. They would also have to promise not to heavily bankroll their own campaigns.

Bonin, who is running for reelection in the March 7 election, made his announcement a week after several council members proposed banning campaign contributions from real estate developers seeking city approvals. Although he signed on to that proposal, Bonin said the city should do more.

“Instead of tweaking the system, let’s fix it and replace it with a better one,” he said.

The city already has a public matching funds system that allows candidates to tap a limited amount of taxpayer money. For example, council candidates can obtain up to $225,000 in public funds as long as they comply with certain requirements, such as raising at least $5 apiece from 200 residents in their district.

Bonin, who represents coastal neighborhoods, pointed to Maine and Arizona as possible models for what Los Angeles could do next. In Maine, candidates for governor can tap taxpayer funds if they show they have raised 3,200 donations of at least $5 from state voters. The donations must go to the state fund that provides financial support to candidates. Once a candidate begins to receive public funds, he or she can no longer receive private contributions.

Public financing is “the absolute right direction for Los Angeles to be moving,” said Kathay Feng, executive director of California Common Cause, an open government group. “Candidates will spend a lot more time talking to constituents — and not just raising money from outside special interests.”

Mark Ryavec, one of the candidates running against Bonin, described the proposal as an attempt to divert voter attention from the donations the councilman has taken from developers and others with business at City Hall.

“If Bonin wants to get developer cash out of City Hall decision-making, he should start by returning the hundreds of thousands of dollars he has raised from special interests over the last four years,” said Ryavec, who heads a Venice group that advocates for slow growth.

The councilman declined to respond, saying his proposal is “not a campaign thing.”

Bonin is reviving an idea put forward in 2005 by his former boss, Councilman Bill Rosendahl, that was studied for years then abandoned. During that debate, a top city analyst warned that full public financing would be “very costly,” requiring either funds from the city budget or voter approval of a new tax.

Bonin said this time around, the city should consider seeking development fees or taxes on oil and gas production to pay for the public financing system. He also argued that presidential candidate Bernie Sanders had helped create a groundswell of popular support for reform.

Caney Arnold, a supporter of the Vermont senator who is running against Councilman Joe Buscaino in a district that spans from Watts to San Pedro, said the proposal would still put too many obstacles before candidates, who already must turn in petitions to get on the ballot.

“Five dollars doesn’t sound like a lot, but getting signatures is tough enough,” said the retired Air Force program manager.

Bonin’s proposal has drawn support from Money Out Voters In, a nonprofit group that focuses on decreasing the influence of money in politics. Such a system would go a long way in addressing voter apathy and disaffection, its co-founder Michele Sutter said.

“People really feel like their representatives aren’t listening to them,” she said. “This will give them the idea that, ‘Hey, my vote, my voice, has no less weight than Mr. Moneybags on top of the hill.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.