School busing and race tore L.A. apart in the 1970s. Now, Kamala Harris is reviving debate

- Share via

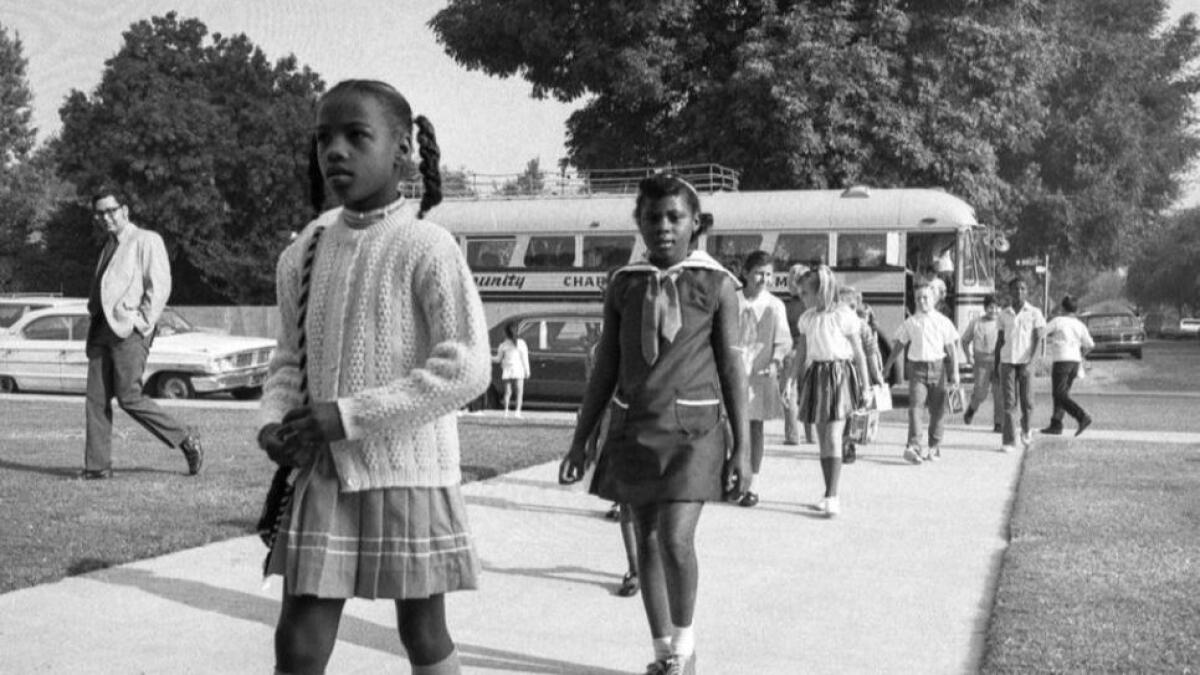

Few issues divided Los Angeles more in the 1970s than school desegregation and busing.

It sparked protests and political movements — and led to white families fleeing from the Los Angeles Unified School District.

These issues came back to life at the Democratic presidential debate. In a heated exchange, Kamala Harris accused Joe Biden of not taking a morally correct position in favor of an assertive federal role in the busing of students to achieve integration.

In California, school desegregation was part of broader integration efforts, including the elimination of redlining, which kept black people and members of other minority groups from living in “white” neighborhoods. It was this practice, in L.A. and elsewhere, that gave rise to mandatory busing as a potential remedy to the harms of segregation. The idea was that schools for all students would improve if white students had to share the fate of black students.

Biden’s position, arguing for a limited federal role in enforcing integration, was a justification that Southern states adopted in trying to thwart the Supreme Court’s mandate. But integration was resisted as well in other parts of the country and certainly in California.

In the late 1970s, more than two decades after the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed segregated schools in Brown vs. Board of Education, L.A. Unified geared up for mandatory busing after failed court attempts to block it.

Spurred by the largely white middle class, a popular uprising swept through local and state politics as crosstown busing was barely getting underway. Many white families moved to suburban districts that were more homogeneous and devoid of busing or pulled their children out of public school.

L.A. voters also recalled school board President Howard Miller. Miller was no fan of forced busing but pledged to enforce the law, which was enough to doom his political career. Elected to the board instead were busing opponents Bobbi Fiedler and Roberta Weintraub.

In 1979, the Legislature placed on the ballot a constitutional amendment, Proposition 1, that effectively ended forced busing. In its wake, L.A. shifted to a voluntary busing system under court supervision. This became the “magnet” program. The idea was to create special academic programs that would be so attractive that they would act as a magnet to draw white students to schools they would not otherwise attend.

Another element of the program simply allowed minority students from low-income South Los Angeles to take buses to schools in the whiter and more prosperous San Fernando Valley. Some of the Valley schools needed a burst of enrollment to fill their classrooms. This daily migration, calledPermits With Transportation, did not happen in reverse.

Busing turned some young African Americans into pioneers, and it was challenging.

“I remember one girl couldn’t have us at her house because her dad objected,” Cynthia Carraway, Birmingham High School class of ’76, told Times columnist Sandy Banks in 2012. “She said, ‘You can’t come over, but I’ll meet you on the corner.’ And we hung out anyway.”

“We felt like we had a responsibility to represent the inner city,” added Peggy Harris, also in the class of ’76.

The magnet effort achieved notable academic successes, such as the Bravo Medical Magnet High School and the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies, but the integration benefit was limited.

Across the nation, the landmark 1954 Supreme Court ruling proved to be more a crack in the door than a flinging open of opportunity. Over time it had an effect, though ever so gradually, according to a May report from the UCLA-based Civil Rights Project.

“The passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act as well as a series of Supreme Court decisions in the 1960s and early 1970s produced momentum towards increased desegregation for black students that lasted until the late 1980s, as districts across much of the country worked to achieve the promise of Brown — integrated schools for all children,” the report noted.

In recent decades, an increasingly conservative Supreme Court has unwound the imperative to desegregate. In 2007, the court ruled that race could not be used as an overt factor in school enrollment at public institutions. Berkeley Unified — where Harris spoke of being a student in a desegregation program — experimented instead with integration based on the economic profiles of census tracts. The idea was to substitute poverty for race in desegregation, in large measure because poverty closely tracked race.

The high court’s more recent actions undermined efforts in some Southern cities, such as Charlotte, N.C., where school desegregation had arguably borne fruit.

Segregation is hardly a Southern legacy alone. New York remains the most segregated state for African American students, with 65% of black students in “intensely segregated” schools, according to the Civil Rights Project. California is the most segregated for Latinos, where 58% attend intensely segregated schools, and the typical Latino student is in a school with only 15% white classmates.

In spite of its stellar reputation, fewer than 3% of the students at the Bravo High magnet, in Boyle Heights, are white; about 82% are Latino.

The 5-4 Supreme Court ruling in 2007 specifically struck down magnet-school programs in Seattle and Louisville, Ky. Seattle was never under a court order to desegregate; Louisville’s court order was dissolved.

Los Angeles was able to keep its magnet program — for which it receives supplemental state funding — because it began in response to a court order. At this point, the court order is something of a legal fig leaf that protects the magnet program, giving it a legal right to continue. It’s not clear that local courts would do anything to force the district to continue the magnet effort.

White students attend some magnet schools in higher numbers than they do other schools, but their overall numbers are small. The district is 73.4% Latino, 10.5% white, 8.2% African American and 4.2% Asian.

A paradigm of L.A.’s recent school construction and modernization program was to improve neighborhood schools so students did not have to leave their neighborhoods — a modern day iteration of separate but equal in a city that remains substantially divided by class and race.

During the debate, Harris alluded to being part of a nascent busing program as a young student in Berkeley, many years after the U.S. Supreme Court ordered school desegregation. The court famously argued that “separate but equal” was not equal in terms of the rights and education afforded to black students.

Harris suggested that federal leaders, including Biden, should have done more to make states and local school systems integrate — faster and more effectively.

Biden responded that Harris was misrepresenting his position. He supported integration, he said, but felt that local agencies should take the lead rather than the federal government. Biden, who served as vice president to the nation’s first black president, then tried to list elements of his record that, he said, defined his strong support of civil rights.

The case against Biden on busing is laid out in detail by author Jonathan Kozol in a piece for the Nation.

Regardless of Biden’s intent, he was among the politicians who successfully surfed the surge of anti-busing populism. This wave included parents who were horrified by overt racism, but who opposed putting their children on buses. And this wave also included avowed racists and opportunists who, in their opposition to busing, hid behind self-righteous platitudes.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.