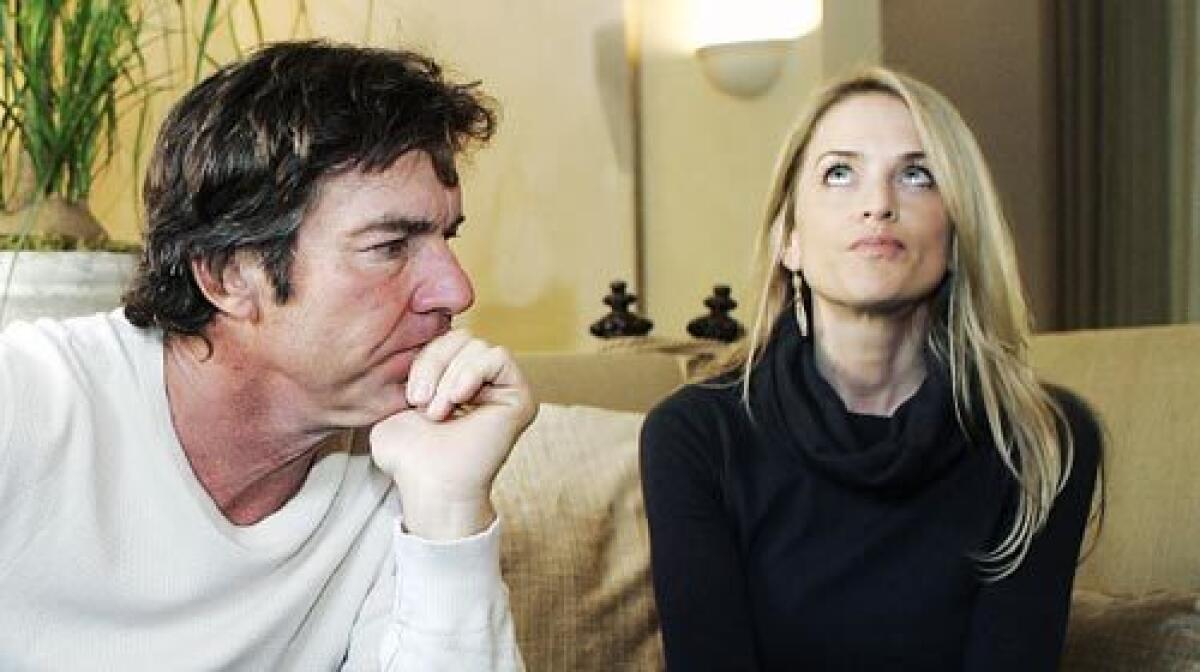

Quaids recall twins’ drug overdose

- Share via

Before actor Dennis Quaid went to bed Nov. 18, he gave one last call to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, where his newborn twins were being treated for staph infections.

“Oh, they’re fine,” Quaid recalled a nurse telling him about 9 p.m. “They’re just fine.”

Actually, they weren’t.

Earlier that day, nurses had mistakenly given Thomas Boone and Zoe Grace 1,000 times the recommended dose of the blood thinner heparin. About two hours before Quaid’s call, nurses had noticed Zoe oozing blood from an intravenous site on her arm and a spot on her heel, state records show.

But that night, even as hospital staff scrambled to reverse the effects of the heparin, Quaid said, no one notified him or his wife, Kimberly, of the crisis.

The first that Dennis Quaid learned of the medication error was at 6:30 a.m. the next day, he said, when he arrived at the Los Angeles hospital. Treatment decisions had been made without them, he said.

“Our kids could have been dying, and we wouldn’t have been able to come down to the hospital to say goodbye,” Dennis Quaid said in a 90-minute interview Monday, the couple’s first since the overdose.

At the door of the children’s hospital room, he said, he was greeted not just by a pediatrician and a nurse but by a representative of the hospital’s risk management department.

A heparin overdose had left the twins’ blood too thin to clot, Quaid said he was told, leaving the premature infants vulnerable to uncontrollable bleeding. They had been given an antidote.

The Quaids said they spent the day watching in terror as doctors and nurses hovered over their critically ill children. At one point, as a bandage was being changed, blood spurted from the area around Thomas’ clipped umbilical cord and hit a wall about 5 feet away, Dennis Quaid, 53, remembered.

“They were in incubators with cords attached to them and monitors, and you could barely hold them,” said Kimberly Quaid, 36. “Every time you’d move them, the alarms would sound. . . . The stress was overwhelming.”

The Quaids said they felt betrayed and misled by Cedars-Sinai, one of the nation’s most prestigious hospitals. And their anger has only grown since the release last week of a report by state regulators, who found that Cedars-Sinai had placed the Quaid twins and others in immediate jeopardy by its improper handling of medication.

The Quaids said they believe someone at the hospital leaked information about the error to the news media. Their own family members, they said, learned that the babies were in the hospital only after the website TMZ.com broke the news Nov. 20, two days after the heparin overdose.

They said they made a deliberate decision not to tell relatives or friends that their children were in the hospital, because they didn’t want to worry them and because they did not want the information to appear in tabloid reports.

“We were told that it was not a big deal,” Kimberly Quaid said. “We figured we’d be home in a couple days and nobody would know any different. That wasn’t the case.”

Cedars-Sinai spokesman Richard Elbaum declined to comment on most of the allegations made by the Quaids. “Throughout the course of their children’s hospitalization and continuing today, we have reached out to the Quaids to discuss any concerns or questions they have,” he said. “We would like to continue to discuss all of these and any other concerns directly with the Quaids to identify and resolve any questions.”

Elbaum did say the hospital is investigating whether there was a violation of the twins’ privacy rights by leaks to the media. “We take very seriously any allegations of breaches of patient confidentiality and investigate these in a comprehensive manner,” he said.

The Quaids have already filed a lawsuit against Baxter Healthcare Corp., one of the manufacturers of heparin, contending that the labeling and design of the product led to the error.

Baxter representatives have said the error resulted from improper use, not the drug itself.

The Quaids’ lawyer, Susan E. Loggans, said the hospital was slow to provide full documentation, and her clients have not made a decision about whether to sue Cedars-Sinai. “We want to see how they respond,” she said. “We’d like to give them a chance to right a wrong.”

On Nov. 8, at 36 weeks gestation, Thomas and Zoe were born at St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica. Although a surrogate carried the babies, the Quaids are the biological parents.

The twins came home three days after their birth. But within days, the parents and a nurse noticed that Thomas had an infection around his navel. Zoe soon developed an infection too.

On Nov. 17, their pediatrician told them to take the twins to Cedars-Sinai.

The babies were placed in a room in the pediatric unit to receive intravenous antibiotics.

The Quaids spent the entire next day at the hospital. “So, our kids are actually being overdosed while we’re there,” Dennis Quaid said.

According to state regulators, the medical errors began the morning of Nov. 18 when two pharmacy technicians mistakenly delivered 100 vials of heparin to the pediatric unit. The vials contained a concentration of 10,000 units per milliliter instead of the appropriate 10 units per milliliter of the blood thinner, which is used to prevent clots.

A short time later, the twins received their first dose of the high-concentration heparin to flush their intravenous lines. They each received a second dose about eight hours later. The nurses involved told inspectors they could not remember whether they had read the label on the heparin vials.

After spending 11 days in intensive care, Thomas and Zoe appear to have made a full recovery, the Quaids said.

“We have our babies back, and they seem to be doing great, and they’re just a lot of fun to be with,” Dennis Quaid said.

“We really do feel that prayer saved them,” he later said.

A third child at Cedars-Sinai also received overdoses but recovered.

Kimberly Quaid said the stress of having critically ill children was magnified by paparazzi, who followed the couple to the hospital and even tried to deliver gifts to gain access.

She also complained of intrusive hospital administrators. “They wouldn’t let us be alone with our children, to the point where we were just like, ‘Can you please just give us a moment?’ ” Kimberly Quaid said. “But regardless, they just kept coming in the room.”

The Quaids said they plan to start a foundation to promote patient safety.

“When you go into a hospital, you become like a child, like an infant in a way,” Dennis Quaid said. “The names of the drugs, we can’t even pronounce. . . . We put complete trust, and we are so vulnerable like a child, innocent and vulnerable in a hospital situation.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.