Special Report: More than 1 million OxyContin pills ended up in the hands of criminals and addicts. What the drugmaker knew

- Share via

In the waning days of summer in 2008, a convicted felon and his business partner leased office space on a seedy block near MacArthur Park. They set up a waiting room, hired an elderly physician and gave the place a name that sounded like an ordinary clinic: Lake Medical.

The doctor began prescribing the opioid painkiller OxyContin – in extraordinary quantities. In a single week in September, she issued orders for 1,500 pills, more than entire pharmacies sold in a month. In October, it was 11,000 pills. By December, she had prescribed more than 73,000, with a street value of nearly $6 million.

At its headquarters in Stamford, Conn., Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin, tracked the surge in prescriptions. A sales manager went to check out the clinic and the company launched an investigation, concluding that Lake Medical was working with a corrupt pharmacy in Huntington Park to obtain large quantities of OxyContin.

“Shouldn’t the DEA be contacted about this?” the sales manager, Michele Ringler, told company officials in a 2009 email. Later that evening, she added, “I feel very certain this is an organized drug ring...”

Purdue did not shut off the supply of highly addictive OxyContin and did not tell authorities what it knew about Lake Medical until several years later when the clinic was out of business and its leaders indicted.

By that time, 1.1 million pills had spilled into the hands of Armenian mobsters, the Crips gang and other criminals.

A Los Angeles Times investigation found that, for more than a decade, Purdue collected extensive evidence suggesting illegal trafficking of OxyContin and, in many cases, did not share it with law enforcement or cut off the flow of pills. A former Purdue executive, who monitored pharmacies for criminal activity, acknowledged that even when the company had evidence pharmacies were colluding with drug dealers, it did not stop supplying distributors selling to those stores.

Purdue knew about many suspicious doctors and pharmacies from prescribing records, pharmacy orders, field reports from sales representatives and, in some cases, its own surveillance operations, according to court and law enforcement records, which include internal Purdue documents, and interviews with current and former employees.

Joseph Rannazzisi, who was the top DEA official responsible for drug company regulation until last year, said he was not aware of the scope of evidence collected by Purdue. Under federal law, drugmakers must alert the DEA to suspicious orders. The agency interprets that law, he said, to include a duty to reject orders from customers if the company suspects pills are going to the black market.

“They have an obligation, a legal one but also a moral one,” he said.

The federal government has not accused Purdue of any wrongdoing in the case of Lake Medical or other suspected drug operations.

In a statement, a Purdue lawyer said the company had “at all times complied with the law.” General counsel Phil Strassburger said Purdue had reduced supplies of OxyContin to distributors servicing some pharmacies it suspected of corruption, but had to be careful such reductions did not to interfere with legitimate patients getting medication.

He defended the company’s decision not to share all its evidence with authorities.

“It would be irresponsible to direct every single anecdotal and often unconfirmed claim of potential misprescribing to these organizations,” Strassburger said.

***

More than 194,000 people have died since 1999 from overdoses involving opioid painkillers, including OxyContin. Nearly 4,000 people start abusing those drugs every day, according to government statistics. The prescription drug epidemic is fueling a heroin crisis, devastating communities and taxing law enforcement officers who say they would benefit from having information such as that collected by Purdue.

A private, family-owned corporation, Purdue has earned more than $31 billion from OxyContin, the nation’s bestselling painkiller. A year before Lake Medical opened, Purdue and three of its executives pleaded guilty to federal charges of misbranding OxyContin in what the company acknowledged was an attempt to mislead doctors about the risk of addiction. It was ordered to pay $635 million in fines and fees.

After the settlement, Purdue touted a high-powered internal security team it had set up to guard against the illicit use of its drug. Drugmakers like Purdue are required by law to establish and maintain “effective controls” against the diversion of drugs from legitimate medical purposes.

That anti-diversion effort at Purdue was run by associate general counsel Robin Abrams, a former assistant U.S. attorney in New York who had prosecuted healthcare fraud and prescription drug cases. Jack Crowley, who held the title of executive director of Controlled Substances Act compliance and had spent decades at the DEA, was also on the team.

Purdue had access to a stream of data showing how individual doctors across the nation were prescribing OxyContin. The information came from IMS, a company that buys prescription data from pharmacies and resells it to drugmakers for marketing purposes.

That information was vital to Purdue’s sales department. Representatives working on commission used it to identify doctors writing a small number of OxyContin prescriptions who might be persuaded to write more.

By combing through the data, Purdue also could identify physicians writing large numbers of prescriptions – a potential sign of drug dealing.

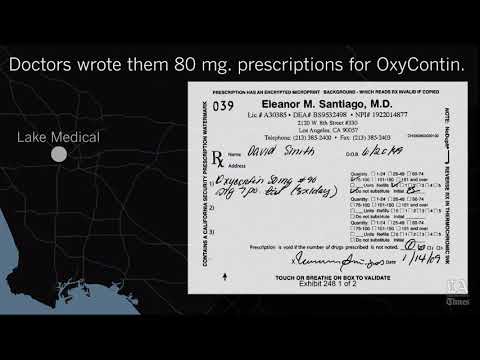

Soon after Lake Medical opened, Purdue zeroed in on prescriptions of 80-milligram, maximum-strength OxyContin written by Eleanor Santiago. Once a respected physician, the 70-year-old was in failing health and drowning in debt when she took the job of clinic medical director alongside several other doctors.

The 80-milligram pills Santiago prescribed had the strength of 16 Vicodin tablets. Doctors generally reserved those pills for patients with severe, chronic pain who had built up a tolerance over months or years.

In the illegal drug trade, however, “80s” were the most in demand.

At the time of Lake Medical, the pills could be crushed and smoked or snorted, producing a high similar to the drug’s chemical cousin, heroin. On the street, the pills went for up to $80 apiece.

A physician writing a high volume of 80s was a red flag for anyone trying to detect how OxyContin was getting onto the black market.

The number of prescriptions Santiago was writing wasn’t merely high. It was jaw-dropping. Many doctors would go their entire careers without writing a single 80s prescription. Santiago doled out 26 in a day.

Purdue was tracking her prescriptions.

Michele Ringler, the district sales manager for Los Angeles and a company veteran, went to Lake Medical to investigate. When she and one of her sales reps arrived, they found a building that looked abandoned, according to company emails recounting the visit. Inside, the hallways were strewn with trash and lined with a crowd of men who looked like they’d “just got out of LA County jail,” according to the emails. Feeling uncomfortable, Ringler and the rep left without speaking to Santiago.

When a Purdue security committee met in Stamford in December 2008, less than five months after Lake Medical opened, Santiago was under review, according to internal records and interviews. The panel, comprised of three company lawyers, could have reported her to the DEA. Instead it opted to add her name to a confidential roster of physicians suspected of recklessly prescribing to addicts or dealers.

Purdue calls that list Region Zero and has been adding names to it since 2002. A Times investigation in 2013 revealed the existence of the list. At that time, the company acknowledged that there were more than 1,800 doctors in Region Zero.

Purdue directed its sales reps to avoid those doctors, and it didn’t tell physicians they had been placed on the list. Company executives told The Times in a 2013 interview that Purdue had reported about 8% of the doctors on the list to authorities.

One doctor Purdue put in Region Zero was Eric Jacobson, a Long Island, N.Y., physician prescribing huge amounts of OxyContin. The company stopped sending sales reps to his office in 2010. The following year, one of Jacobson’s patients killed four people, including a high school student, in a pharmacy robbery.

In the investigation, authorities discovered that Jacobson had been selling prescriptions to dealers and addicts for years. The doctor “directly contributed to the tragedy of prescription drug abuse that has swept our district and our nation,” said Loretta Lynch, then the region’s top federal prosecutor, now the U.S. Attorney General.

Jacobson was convicted of unlawful distribution of oxycodone. The prosecutor and lead investigator told the Times that Purdue did not disclose what it knew about Jacobson to them either before or after the pharmacy slayings.

***

This motion graphic shows how OxyContin flowed out of Los Angeles.

In L.A., Santiago kept churning out prescriptions in ever larger numbers.

To keep the OxyContin flowing, Lake Medical needed people. Lots of them. Age, race and gender didn’t matter. Just people whose time was cheap. For that, there was no place better than skid row.

Low-level members of the Lake Medical ring known as cappers would set up on Central Avenue or San Pedro Street. The stench of urine was everywhere. People were lying in doorways, sleeping in tents, fighting, shooting up. Who wants to make some money, the cappers would shout.

For as little as $25, homeless people served as straw patients and collected prescriptions for 80s. It just required a few hours at the clinic, filling out a few forms and sitting through a sham examination. They were then driven, often in groups, to a pharmacy, where a capper acting as a chaperone paid the bill in cash. He then took the pills back to the Lake Medical ring leaders who packaged them in bulk for sale to drug dealers.

The pills from Lake Medical coursed out of L.A. An informant would later tell an FBI agent that East Hollywood’s White Fence gang trafficked pills to Chicago, according to the agent’s report. A Crips leader from the Inland Empire also bought OxyContin from Lake Medical, according to law enforcement records.

In the months after the Lake Medical ring started, Purdue was informed that homeless people were being used in an OxyContin ring. In December 2008, the same month Santiago was placed on the Region Zero list, a company sales rep visited Central Care Pharmacy, an Encino store filling Lake Medical prescriptions. The pharmacist said there appeared to be some kind of scam going on with 80-milligram pills, according the sales representative’s report to headquarters. They’re shuttling homeless people around to pharmacies, the pharmacist said.

Purdue sent Ringler to follow up and her report on the pharmacist’s concerns reached Purdue’s security and risk management teams the next day.

**

Pharmacist complaints about Santiago kept piling up.

“The first few of these prescriptions…looked legitimate…[but] after those were filled, a steady flow of younger, more ambulatory, customers came in with the same prescriptions,” a Temple Street pharmacist told a Purdue representative, according to a January 2009 field report.

Pharmacists from La Canada, Glendale, Moreno Valley and elsewhere also complained to Purdue. Company executives and lawyers received at least 11 reports about Santiago in the four months after they placed her in Region Zero.

On June 10, the Encino pharmacist sent an email to her Purdue sales rep with the subject line “urgent question.” The pharmacist said she was being asked to fill prescriptions written by Santiago and other Lake Medical doctors for “lots of Oxy patients.”

“I want to make sure Dr office is legit,” Tihana Skaricic wrote. “So wondering…if you know ‘behind the scenes.’”

The email was forwarded to Ringler, who sent it to a company lawyer, who sent it to Crowley, an executive responsible for compliance with the federal controlled substances law. No one at Purdue ever got back to Skaricic, she said in an interview. Eventually she and some other pharmacists decided on their own to turn away business from Lake Medical.

Had Purdue passed on its concerns, Skaricic said, “I would have stopped filling these prescriptions way earlier.”

***

With a few keystrokes on his computer at Purdue, Jack Crowley could identify pharmacies around the country that were moving a staggering volume of 80s and almost nothing else.

“I could punch it in at any time…Bang,” Crowley told the Times. “I was sitting on a gold mine.”

Crowley retired from Purdue in 2013 and works in Georgia for a pharmaceutical consulting company. After The Times approached him, he agreed to a series of interviews in which he talked at length about the inner workings of Purdue’s security operation.

Until a decade ago, Purdue, like most drug manufacturers, didn’t monitor pharmacies for criminal activity. The DEA has held wholesalers, not drugmakers, responsible for identifying and reporting suspicious orders from their customer pharmacies.

In 2007, the DEA pressured drug manufacturers to do more to stem the prescription drug crisis and warned that it would be looking at every step in the supply chain. In response, Purdue decided to gather detailed information about pharmacies, Crowley said.

The company approached wholesalers and struck agreements allowing the company access to their sales reports. With the new data, the security team in Stamford could see all wholesalers’ OxyContin sales to individual pharmacies, down to the pill.

“I can look at something and say, ‘Geez, that stinks’ without me even visiting the place,” Crowley recalled.

The DEA had access to similar pharmacy purchasing data, but many investigators regarded the database as unwieldy because it encompassed dozens of drugs sold by more than a thousand companies and could be up to six months out of date.

As Lake Medical entered its second year, Crowley’s computer screen showed a handful of small pharmacies in the L.A. area suddenly ordering eye-popping amounts of maximum-strength OxyContin.

At one San Marino store, Huntington Pharmacy, monthly orders for 80s were up nearly 20-fold over the previous year. At another in East L.A., orders jumped 400% in two months. A small shop in Panorama City, Mission Pharmacy, became the top seller of OxyContin in the entire state of California.

Purdue added those store names to a long list of problematic pharmacies across the country. Each month, a group called the Order Monitoring System committee -- Crowley, company lawyer Abrams, the chief security officer, a sales executive and others -- met to discuss what to do about the stores, according to security team memos.

Some on the committee argued for reporting suspicious pharmacies to the DEA and instructing distributors to stop selling to those stores, Crowley said. But he and others felt it was up to the distributors to take action, he said, noting that company policy prohibited employees from reporting pharmacies to the DEA without first consulting their distributors.

In the case of Mission in Panorama City, a top supplier to the Lake Medical ring, the committee decided the best course was for Crowley to “continue to watch” the situation, according to an internal company email.

In an interview, Crowley said that in the five years he spent investigating suspicious pharmacies, Purdue never shut off the flow of pills to any store.

Pharmacies were allowed to buy OxyContin even in cases when Purdue security staffers personally witnessed suspicious behavior. Crowley said during visits to two San Francisco pharmacies, he saw homeless people filling prescriptions and then handing the bottles off to men he suspected were drug dealers. In 2009, he and a Purdue investigator went to Las Vegas to check on Lam’s, a pharmacy next to a bar in a mini-mall that Crowley said was one of the top five sellers of OxyContin in the nation.

He and his colleague sat in their rental car watching crowds of young people come and go with pills, Crowley said.

“It was terrible,” he recalled. “It was just a drug-distribution operation.”

Crowley said he phoned in a tip to a DEA agent he knew in San Francisco, and Mark Geraci, the company’s security chief, wrote a letter to the DEA about Lam’s. But the company did not share the telltale sales data with the DEA or others in law enforcement, Crowley said. With Lam’s, some wholesalers decided to stop supplying the store and Purdue ultimately limited the amount of OxyContin the pharmacy’s remaining wholesaler could buy. But in that case, and in San Francisco, the company did not cut off the wholesalers completely.

Federal prosecutors in Las Vegas later targeted Lam’s, charging a local drug dealer, an 87-year-old doctor, a pharmacist and others with participating in a criminal ring that furnished pills to addicts as far away as Ohio and New Hampshire. Several were convicted. Others are awaiting trial.

In Southern California, one of Purdue’s OxyContin distributors eventually noticed a troubling spike in sales at St. Paul’s Pharmacy in Huntington Park, which was filling prescriptions for Lake Medical.

“They are buying a lot of Oxycontin 80s from us,” the security chief for distributor HD Smith emailed Crowley in August 2009.

Purdue knew St. Paul’s orders for 80s were up nearly 1400%. But the company’s monitoring committee “hadn’t gotten around to discussing” the store, Crowley wrote in an email to colleagues, and he asked Ringler, the L.A. district manager, to investigate.

The pharmacist told Ringler his business “exploded” when he started filling 80s for Lake Medical doctors, according to series of emails and reports on her August 2009 visit.

Ringler asked the pharmacist if the cash transactions for maximum-strength OxyContin concerned him, according to the emails, but he declined to answer. When she suggested he call law enforcement, “he said he didn’t want to get audited by the DEA,” Ringler told supervisors. “I told him that eventually the DEA will track down where these Rxes are getting filled.”

HD Smith cut off shipments to the pharmacy after her visit, but other distributors still filled orders from the store and other pharmacies were filling prescriptions from doctors at Lake Medical.

In an email to Crowley and others at Purdue, Ringler said the drug sales were “clearly diversion” – illegal use or distribution of pharmaceuticals.

Reaching out to the DEA “is under serious consideration,” Crowley replied. Ringler pushed back, telling him that Lake Medical was “very dangerous” and “an organized drug ring.”

“It just seems that trained professionals like the DEA would be better equipped to do further investigation of this clinic,” she wrote.

“Thanks, Michele,” Crowley replied. “We are considering all angles.”

In his statement to The Times, Purdue’s general counsel, Strassburger, acknowledged that the company is “required to monitor and report suspicious orders to the DEA,” but he noted that “Purdue does not ship prescription products directly to retail pharmacies; it sells only to authorized wholesalers, who maintain their own order monitoring programs.”

“Once Purdue identifies the potential suspicious activity of a wholesaler’s customer, Purdue informs the wholesaler, so they can perform their due diligence…,” Strassburger said.

In the case of Lake Medical, Purdue didn’t notify some distributors that it suspected St. Paul’s was part of a drug ring. Five months after HD Smith stopped shipments, another wholesaler concerned about St. Paul’s reached out to Crowley seeking information about the store.

***

In the end, the Lake Medical ring was brought down by a team of state, federal and local investigators that collected tips from citizens and spent hours staking out the clinic, interviewing witnesses and turning junior ring members into informants. When Lake Medical closed in 2010, after a year and a half in business, Purdue had still not shared its wealth of information on the clinic with the authorities, according to law enforcement sources.

In an email to a distributor after the arrest of Santiago and the clinic operators, Crowley criticized the pace of the government investigation.

“It really takes the ‘G’ a long time to catch up with these jokers,” he wrote.

In a memo to supervisors after the clinic was shuttered, Ringler noted that more than 20 doctors in her territory were still doling out large amounts of 80s, some using the same pharmacies Lake Medical had used. She suggested that Purdue use its databases to “proactively” report suspicious prescribing, across the country, to insurers as well as law enforcement.

Purdue did not respond to questions about the proposal. Crowley said he was never told about her plan. Ringler declined to speak to The Times.

The company introduced a new, tamper-resistant OxyContin tablet in August 2010. Addicts found them almost impossible to smoke or snort. Within months, the old 80s were gone from the streets and many dependent on the pills switched to heroin, which was chemically similar and readily available.

In December 2011, two months after the Lake Medical arrests, Purdue lawyer Abrams emailed a DEA official in L.A. the names of local doctors it suspected of misprescribing OxyContin. Santiago, who had already been arrested, was on the list.

“Basically, it was old news,” said Mike Lewis, then the agency’s diversion program manager in L.A. The doctors were “people we were already actively investigating or cases we had taken action on.”

Two years later, in 2013, Abrams called the U.S. Attorney’s Office in L.A. with an offer of assistance, according to an investigator’s report. The company turned over hundreds of pages of internal records about the Lake Medical ring and other suspicious operations in Southern California, which Purdue’s Strassburger said were used by federal prosecutors.

By the time Purdue approached prosecutors, the ring had been out of operation for more than three years and Santiago had pleaded guilty to healthcare fraud. (She was later sentenced to 20 months in prison.) Prosecutors had already built cases against the other ring participants.

Clinic operators Mike Mikaelian and Anjelika Sanamian pleaded guilty to conspiracy to distribute controlled substances and other crimes in 2014 and received sentences of 12 and eight years. The St. Paul’s pharmacist, Perry Nguyen, was sentenced to six months in prison for financial crimes connected to the drug case.

In hindsight, Crowley said, he questions whether Purdue should have done more.

“Are we responsible for diversion at the pharmacy level?” Crowley said. “Well, once we start to learn about it, we’ve got to report it. That’s for sure.”

About this story

This is the second part of a Los Angeles Times investigation of OxyContin, the nation’s bestselling and widely abused painkiller.

The story is based on interviews with current and former Purdue employees, law enforcement officials, medical professionals, pharmaceutical industry experts and others as well as court filings, law enforcement records and internal Purdue documents. Those company records come from court cases and government investigations and include many records sealed by the courts.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.