Pièce de résistance

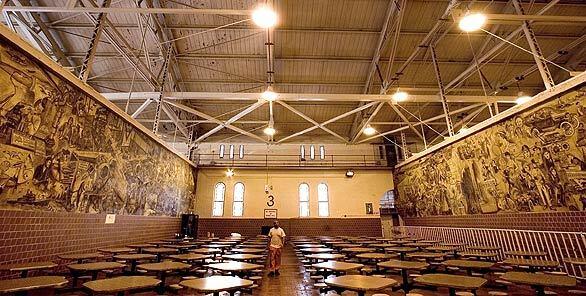

Alfredo Santos was sent to San Quentin State Prison in 1951 on a heroin charge. He left his mark on the stateÂ’s oldest prison by painting 4 100-foot-long California-themed murals in the mess hall. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

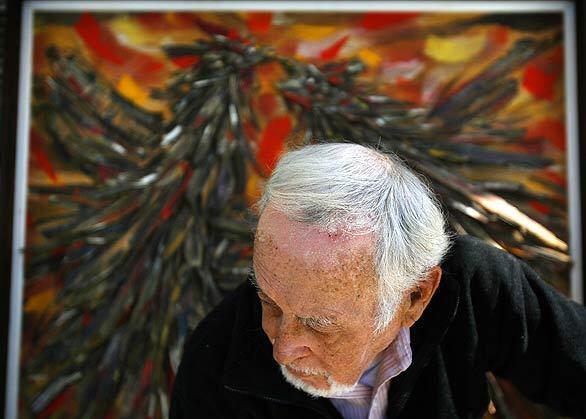

After Santos was released on parole in 1955, memory of his role in painting the expansive murals began to fade from memory at San Quentin. For decades Santos kept quiet about his greatest work of art, ashamed of the time spent in prison. After he revealed himself as the long-sought painter and asked to see his work again, a gala was held in 2003 to recognize his contributions, and he was given an honorary key to the prison. (Robert Durell / Los Angeles Times)

Santos holds a photo of himself taken while he was working on the murals. He painted the four expanses over the course of two years, after which he was released on parole and went to work as a caricature artist at Disneland. Over the course of his prolific career, Santos spent time in San Francisco, San Diego, New York and several cities in Mexico. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

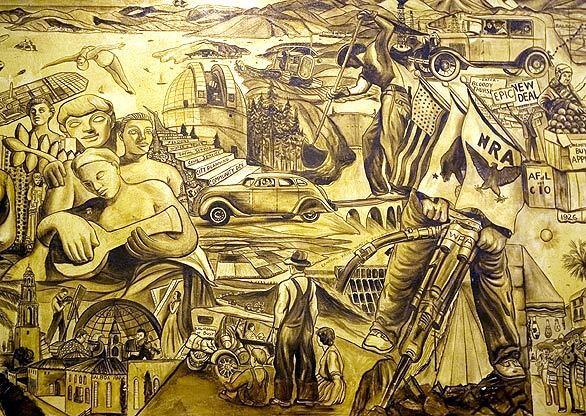

The murals outline major events in California history, from the Gold Rush and the Great Depression to the rise of Hollywood and creation of the state’s elaborate freeway system. A San Francisco streetcar is pictured near the Golden Gate Bridge, along with the Hollywood Bowl and the Coliseum. Santos’ technical skills improved as he went along, as evidenced by the final mural, which demonstrates a modernist style with impressive depth of field. (Robert Durell / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Water damage and vandalism by other inmates now mar the murals, and a bad lacquer job several years ago made the paint turn from red to brown. That gave rise to a lingering jailhouse rumor that the murals were made from coffee grounds and shoe polish. In reality, Santos was only allowed one color to paint with, because officials feared inmates would steal the paints and dye their clothes attempting to escape. (Robert Durell / Los Angeles Times)

Before he moved to New York as a young man, Santos consulted a fortuneteller in Mexico City. She told him that he would get ripped off and die penniless back in Baja Mexico. As he reflects on prolific, if unprofitable, career, Santos says he may prove her right. “I’m the worst businessman in the world,” he said. “I gave a lot of my work away. Lost so many. Got ripped off. That’s what happens to artists. . . . I always said I’m not going to become famous until after I’m dead.” (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)