Healing Sgt. Warren

On a hellish day in Iraq, he watched his friend burn. Should he have done more, he wondered?

- Share via

J

onathan Warren walks through the maze of corridors until he finds the little room. Anxiously, he puts on the earphones and adjusts the wraparound visor. The image before him is crude: Road, desert, truck.

Describe that day, his therapist says.

We drove up in a Humvee...

No. Tell it as if it's happening now.

We are on a black route. The worst kind.

He isn't sure he can trust his memory. He knows he was in the commander's seat, right front. Scott Stephenson, his best friend, was sitting behind him. They had been inseparable since they enlisted two years earlier, the God-fearing California surf punk and the half-crazy Kansas street kid. They bunked together, drank together, learned to shoot together. They were lost boys reborn as hard Army muscle, shaved heads in Kevlar helmets, feeling as bulletproof as their steel-plated, 12,000-pound truck.

Staring into the visor, Warren studies the computer simulation of gray pavement stretching before him. He knows what lies down that road, amid the flames and churning black smoke: the test his whole life was supposed to prepare him for. For years, he's fled the memory, drinking until he can't recognize himself, smoking pot until he's numb, swallowing pills until he can sleep.

Now, the therapist insists that he slow the memory to a crawl, uncoil it, examine it inch by inch.

He closes his eyes. His heart pounds. He sees it now, the worst part, the moment he glances back at the burning truck and realizes Scotty is trapped inside.

What do you see? his therapist asks.

A fireball.

What do you do?

Warren dons his Army uniform before attending a ceremony honoring veterans at Vanguard University. He was skilled at masking his torment.

FLEEING A MEMORY

In the dream from his boyhood, Warren and a younger brother are being chased through the woods by a swarm of vicious bees. His brother falls behind. To save him, Warren sacrifices his own body.

That was how he saw himself. His life made the most sense to him whenever he took a punch in a schoolyard fight for a brother, or threw a punch on behalf of an insulted girl, or played football with a dislocated arm because his high school team needed him.

"He was born with a savior complex," says his mother, Denise.

He grew up the oldest of three brothers in a five-bedroom tract home in Laguna Niguel, with evangelical Sunday school and a strong sense of God's personal disapproval. "You don't have permission to be a child. You have to be perfect," his mother says, ruefully now, of the upbringing she gave him. "There are only two options. You're either saved or you're going to hell."

In school he was popular, a good student, with light blond hair and broad shoulders, an image from a surf-wear poster. But his mother sensed a seething anger that he felt free to vent only when he was brawling or wearing a football uniform.

He started a fight club at a Christian college, where he lasted just two semesters. Boredom was suffocating him, making him do crazy things. He rode waves till 2 a.m. and led drinking trips to Mexico, where he danced with someone else's girlfriend and left the bar with his nose turned sideways.

He grilled cheese steaks at Hooters. He mixed cocaine with Robitussin and saw demons. His parents braced for the late-night call informing them that he was in jail or dead.

He longed for the sense of warrior camaraderie he had seen in "Saving Private Ryan" and "The Thin Red Line." He ached to do "something hard-core," like Denzel Washington's one-man stand against a kidnapping syndicate in a favorite film, "Man on Fire."

He was angry about 9/11, and eager to fight in the war on terrorism, which he saw plainly as a war of good versus evil.

His father, a produce broker, found him at the computer one night studying an Army recruiting website. Tim Warren pleaded with his son to consider an easy paycheck in the family business. Or, if he had to join the armed forces, why not pick a branch more remote from the killing and dying?

Warren heard fear in his dad's voice. It didn't matter. He could already feel the uniform.

Video: Healing Sgt. Warren

Nov. 25, 2006. They were lost, somewhere south of Baghdad. They sweltered in their ceramic armor and the Humvee's thick air. It was the end of a long morning patrol, and they were leading a five-truck convoy through the dangerous borderlands between Sunni and Shiite militias. At nearly noon, the sun was climbing toward its cruelest angle.

For the first time in longer than he could remember, Warren liked himself. He was 24, a good soldier, cool under fire, a peacemaker among bickering troops, and, he believed, equal to anything. "Everything you want in a team leader," said his commander, who had promoted Warren to that job — which usually went to sergeants or above — even though Warren had just made corporal.

Because his middle name was Wayne, buddies in the 3rd Battalion, 509th Infantry, called him "The Duke." Just before he went to war, in an email to family and friends, he wrote of feeling "very excited and blessed to get to go over there and serve."

His first day on patrol, he narrowly escaped injury from a roadside bomb. He wrote with pride of his calm amid the mayhem, adding: "I am now officially a combat veteran!"

Of the four fellow soldiers in this truck, Warren felt closest to Stephenson — a 22-year-old from small-town Kansas with a devilish grin, a professional rapper's wardrobe and a vain regard for his good looks. They'd been together since basic training at Ft. Benning, Ga., day and night for two years, cutting up, surviving brutal drills from the Alaska tundra to the Thai jungle, always waiting for their moment at the heart of this war.

A former high school fullback, Stephenson couldn't pass a mirror without flexing. He would look at the smirking blue-eyed jock in his driver's license photo and declare: "Gorgeous." He had enlisted, at his mother's urging, to escape the drug scene in Atchison, Kan., that she believed would kill him.

The other men in his squad nicknamed him "Oreo," because he was a white boy who freestyled hard-core rap and liked to slouch up to black women in bars, laying down a machine-gun street patter. He kept a closetful of flat-billed hats and meticulously matched sneakers, and worried so much about his clothes that buddies said he reminded them of their girlfriends.

Warren was ready to die for any man in this truck, but he felt a special protectiveness toward Stephenson. Maybe it was because he was so far from home and missed his two little brothers so intensely ... maybe because Stephenson, two years younger, looked as though he needed a big brother ... maybe because he wouldn't listen to anybody else ... maybe because big brother was the role in which Warren felt most comfortable.

Scott Stephenson and Jonathan Warren on patrol in early November 2006. They'd been together since basic training at Ft. Benning, Ga. (Photo courtesy of Jonathan Warren)

From basic training on, Stephenson had bristled at any sign of disrespect, running his mouth at commanders and accepting his punishment with defiant glee. He refused to look miserable when he was forced to do knee-bends around the base while shouldering his 17-pound machine gun.

"Scotty, I can't stop smoking you till you get the message," said Warren, who was supposed to oversee that particular punishment. His friend told him he didn't blame him and kept smiling.

Once, on a night Stephenson would spend in the drunk tank, he kept trying to squirm out of his handcuffs, yelling "It doesn't hurt!" at the cops who were Macing him outside a bar near Ft. Bragg, N.C. Warren was there, shouting: "Shut up, Scotty!"

For all that wildness, Warren saw in him an excellent soldier — the best machine-gunner at the range. He thought so much of his abilities that he picked him for his squad. He was the reason Stephenson was on this road, in this Humvee.

Now, Stephenson was sitting behind Warren in the saw-gunner's seat, a photo of his 1-year-old son in his wallet. Directly beneath him was the truck's diesel fuel tank.

Where are we going? The men were grousing, wondering whether their lieutenant — directing them by radio from the truck behind them — knew the way back to base. Along the road, Iraqi parents were hustling their children indoors at the sight of the Americans.

The radio ordered them to hang a right onto a narrow, nameless dirt road. It ran through waist-high grass along a canal. Nobody knew when it had last been swept for explosives.

The bomb, hidden beneath a thin layer of gravel, was made of 155-millimeter artillery rounds, probably leftover munitions from the disbanded Iraqi Army. To maximize carnage, it was attached to a propane tank. It did not detonate the moment the truck's right front wheel depressed its pressure plate.

Warren passed over it, unaware he was experiencing his final moments as a personality he recognized. It exploded right below his friend, the fragments shredding the fuel tank and floorboards.

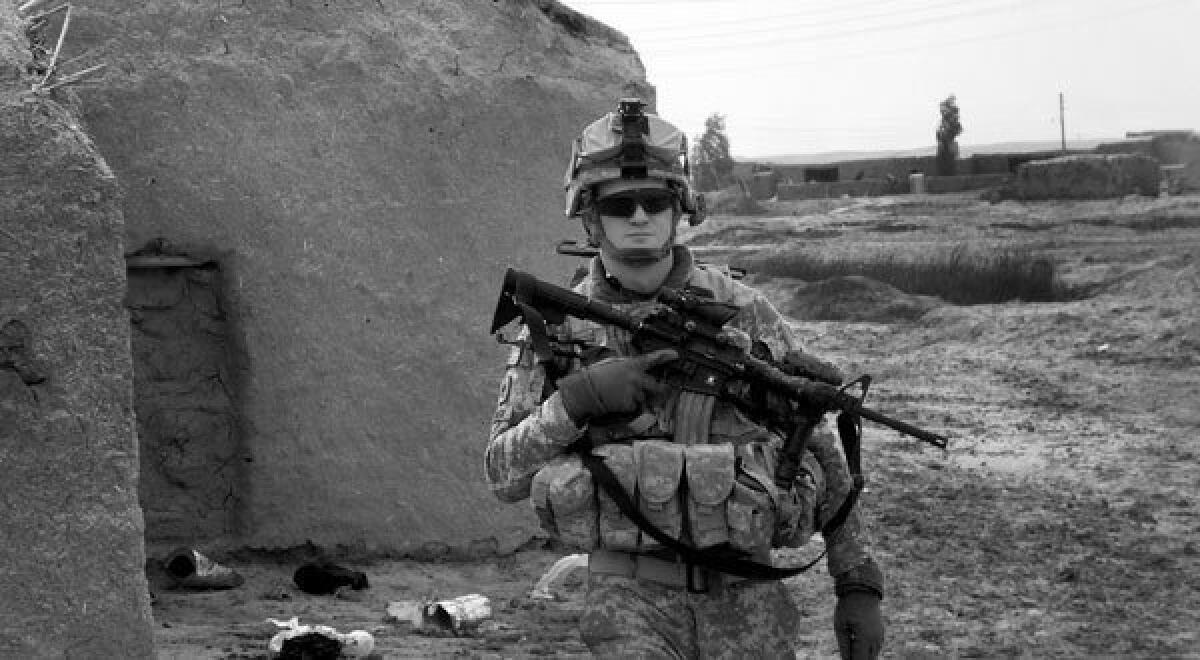

Jonathan Warren on patrol in Iraq. He was "everything you want in a team leader," said his commander. (Photo courtesy of John Cooley)

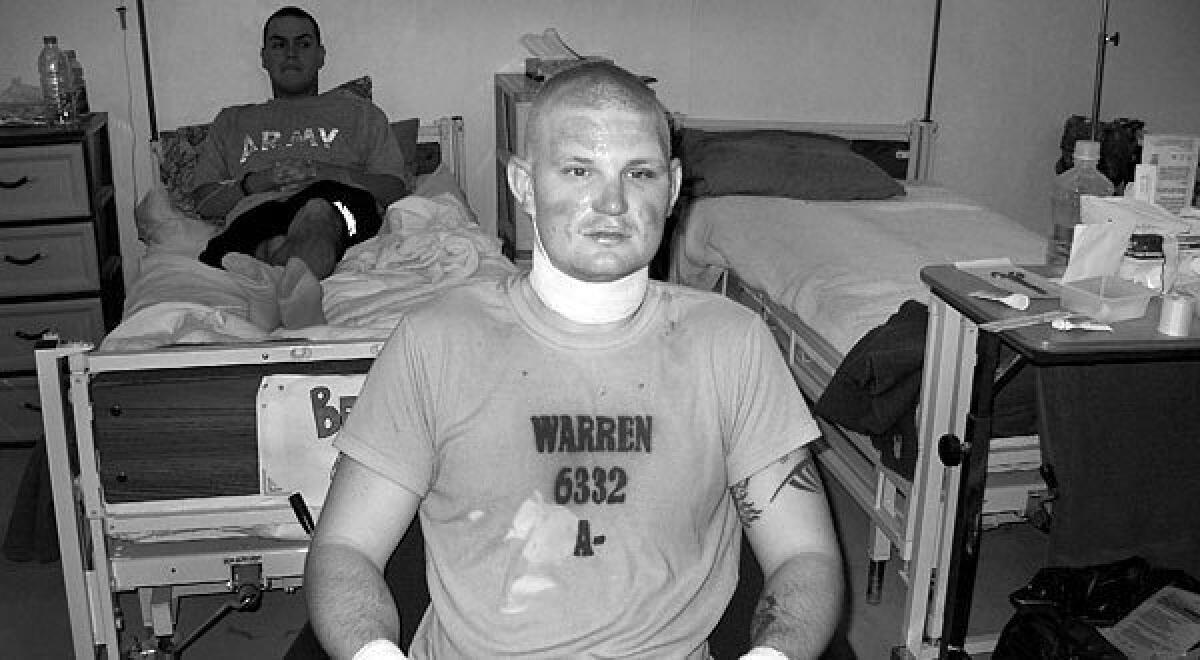

Warren escaped serious injury. Stephenson’s chances of survival were put at 5%. (Photo courtesy of Kathleen Curran)

Warren woke to find himself in a furnace. He heard the shrill screaming of someone in terror. He realized it was himself. Fire ate at his neck and face.

He inhaled a scorching lungful of smoke. He shoved open the Humvee's heavy steel door and rolled into the dirt, extinguishing the flames on his body.

Stephenson was trapped inside, weighed down by his ceramic armor plates and bulging ammo pouches, drenched head-to-toe in diesel from the truck's punctured tank and propane from the bomb. He was being consumed.

Warren did what a soldier does, what he always expected he would do in such a situation: He raced to rescue his friend. The wall of flame repelled him. He couldn't will himself through it. Stephenson kept burning.

And then Stephenson was out, shambling blindly toward the reeds that flanked the nearby canal. His insides were ripped by shrapnel. His left arm dangled by tendons. His left leg was shredded. Warren screamed: Drop! Roll!

Stephenson heard him and tumbled, on fire, into the blast crater.

Now Warren was on top of him, patting frantically at the flames, heaping on fistfuls of dirt. Stephenson's uniform was burning, his skin was burning, his hair was burning, diesel was burning. The smell filled Warren's nostrils. Nothing worked.

Warren couldn't bear to watch. He staggered away. Collapsed. Crawled. Turned around.

Stephenson's voice was strangely calm:

Please help me, Jon.

The wait seemed interminable. Then Warren saw a pair of boots and knew it was the medic, rushing over with a fire extinguisher. Warren was on his feet again, unwrapping rolls of gauze to press against Stephenson's wounds, dragging his friend to safety while the Humvee's cargo of rockets and ammunition ignited.

Stephenson was conscious long enough to ask about his genitals. Were they intact? "Yes." Then: "Am I going to die?"

No, Warren said. He held him until he heard the chopper and hunkered over him to shield him from rotor-whipped sand and debris.

They rode the helicopter 30 miles north to Baghdad Hospital in the Green Zone. Stephenson's chances of survival were put at 5%.

'I DIDN'T SAVE HIM'

Of the truck, there was nothing left. A blackened shell. Collapsed roof. Naked rims where the tires had melted away.

Somehow, Warren had escaped with a concussion, a gash on his head, burns on his face and wrists. Somehow, three of the other four men had survived without critical injuries.

From his hospital in the Green Zone, Warren received fragmentary reports about Stephenson. He was in a drug-induced coma; he was in surgery in Germany; he was fighting off infections; he was having his skull drilled; he was clinging to life at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio.

He managed to reach Stephenson's mother, Luana Schneider, who had sneaked a cellphone into the ICU. Scotty's fighting, she said. She didn't say that he had already endured 20 surgeries, and that she recognized him only by the color of his eyes and the shape of his eyebrows.

She had the impression Warren had pulled her son from the flames.

"Thank you, thank you, thank you for saving my son," she said.

"I didn't. I didn't save him," Warren insisted.

He kept thinking of how he failed to charge into the flaming truck to pull his buddy out. Was it vanity that stopped him? Was he worried about his looks?

And why had he crawled away as his friend burned?

The Army gave Warren a Purple Heart and put him back on patrol. His eyes were hypersensitive. Daylight speared into his brain. He fought through headaches so painful they brought tears. At night his heart beat so hard he thought he felt his bed shaking.

On patrol he popped Clonazepam, a sedative, to steady his nerves. Three soldiers from his company were killed in one 12-day span. Shrapnel from a roadside bomb slashed his knee. The Army gave him another Purple Heart and made him a sergeant.

When he flew home on a three-week leave, his parents decked their home in American flags and invited everyone they knew. People greeted him in T-shirts that read "JON'S OUR FREEDOM FIGHTER." They nibbled from cheese plates and veggie platters. He plastered a smile to his face and pretended he didn't want to scream.

"Promise you'll stay safe," his grandmother pleaded. He snapped: How could he promise that?

At a wedding, he stared down a 12-year-old who asked: "Have you killed anybody?"

At night he binged on vodka. Once, his family found him in a delirium. He had flipped over a bedroom mattress, believing friends were trapped inside. He demanded a knife and cried: "I have to get them out!"

On the day before he returned to war, he flew to Kansas City and rented a car. He drove for an hour through bean and tobacco fields to Stephenson's hometown of Atchison. His mom had converted the living room of her three-story Colonial into a bedroom for Stephenson because he couldn't get up the stairs.

Warren wasn't sure what Scotty would look like, nine months after the explosion. He had always known him as cocksure, athletic, girl-crazy. Now he found him in a wheelchair, heavily drugged, 75 pounds heavier. Unable to regulate his body temperature, he had to stay out of the Kansas summer heat.

The bottom half of his face was scarred and crimson, as was 60% of his body. His left leg was gone below the knee. Doctors had removed his adrenal gland, a kidney, his spleen and part of his pancreas, and were pessimistic about his chances of walking again.

His left arm was maimed. He had suffered three strokes and flat-lined on two operating tables. He would become accustomed to people gawking; sometimes he snarled, "Five dollars for the freak show!"

His mother spent eight hours a day on his wounds, showering him, scrubbing dead skin away so vigorously that he bled, wrapping and unwrapping his bandages, enduring the bottomless rages of a young man who knew his former life was gone.

"This is never going to get better!" he screamed.

Warren and Stephenson had dinner at a riverfront restaurant, and afterward Warren pushed his friend's wheelchair into a bar. Stephenson kept asking about their squad; he wanted to go back and fight. They didn't talk about the bomb.

The friends drank more beer back at the house and played Madden Football on the Xbox. Stephenson balanced the joystick on his lap and delighted in beating Warren with his one good hand.

Long after midnight Warren carried him to bed, and Stephenson thanked him for coming all this way to be with him for just a few hours.

"Good night, brother," Warren said.

After Stephenson was asleep, Warren sat there listening to his friend's breathing. Somehow, compared to what he felt now, the demands of war were easy. At 3 a.m. he climbed into his rental car and headed back through the bean and tobacco fields in the dark.

Stephenson shares a hotel room in Las Vegas with Warren. Stephenson had learned to walk on a prosthetic leg and gone through PTSD therapy.

Summer 2011. He'd been out of the army for a year, surviving on disability benefits and the GI Bill. His war ran together as a blur of concussions, villages, dirt roads, checkpoints, bazaars, Humvee cabs, mess halls, bunkers, mortar attacks, raids, 21-gun salutes, eulogies.

His knuckles went white on the wheel when he spotted a box or pile of trash discarded on an American freeway: That's where bombs hid. Selecting clothes for his civilian life, he made it to the changing room at Nordstrom before panic overtook him. At Wal-Mart, his hands turned clammy, his mouth dry; he abandoned his shopping cart.

He checked and rechecked the locks on his Costa Mesa apartment. He wrapped himself in a fog of pot and alcohol. He snapped at his parents until they were scared to approach him. He pushed away a girlfriend he had once longed to marry. Years of hard muscle melted off his frame.

To explain the feeling that lived inside him, he pointed to his midsection, where what he called "this crushing thing" resided like a great tumor.

"Like I know the reality about the world," he said, "and it's not good."

He was adept at hiding his torment. He had a level gaze, disarming smile and easygoing charm, which he deployed like blast walls.

He looked for ways to fix himself. He bought a diesel-fueled Chevrolet Silverado, because the smell of diesel hurled him back to the horror of watching Stephenson burn and he was determined to make himself immune by constant exposure.

He enrolled in psychology classes at Vanguard University in Costa Mesa, hoping to understand his damaged mind. But he struggled to keep his voice from shaking in class. The former infantryman who had led men into battle now sat anxiously, watching the door, in a roomful of college kids.

When people asked about the war, he sounded like a man recounting a video game he just happened to have played. "We were driving," he would say. "We were hit. My buddy got burned up."

One day he volunteered to drive his 17-year-old brother, Logan, to the family's house on Lake Mead. His parents balked. They no longer trusted their binge-drinking son. He pushed his way out of the house and sat in his truck and shook.

Warren holds his friend's prosthetic leg. Stephenson would become accustomed to people gawking; sometimes he snarled, "Five dollars for the freak show!"

Warren and Stephenson share stories of their time together in Iraq while attending a veterans event in Las Vegas. Warren regarded him as a little brother.

In the years since the bomb, Stephenson had learned to walk on a prosthetic leg and gone through therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder. He and his mother traveled the country, talking about their experiences.

His anger and bitterness had abated. He had a quick smile and a mental encyclopedia of dirty jokes. He had girlfriends and a closetful of fedoras. His young son broke a leg off each of his GI Joes so they would resemble his dad.

Warren saw him maybe once a year, and they would fall into their old rhythms almost instantly, laughing, swapping infantry stories, trading lines from "Team America: World Police" and "Anchorman."

But Stephenson could hear the despair creep into his friend's voice — a tone he remembered from his months in the Army hospital, where every day seemed to bring news of another suicide.

"Get help," Stephenson said.

Warren went to a Veterans Center. They offered group therapy. He didn't want a roomful of ex-soldiers to see him broken and helpless.

He went to the therapist who served his college. The therapist had no training in dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder.

He went to the VA hospital in Long Beach. A staffer told him it would be months before he could see a PTSD specialist one on one.

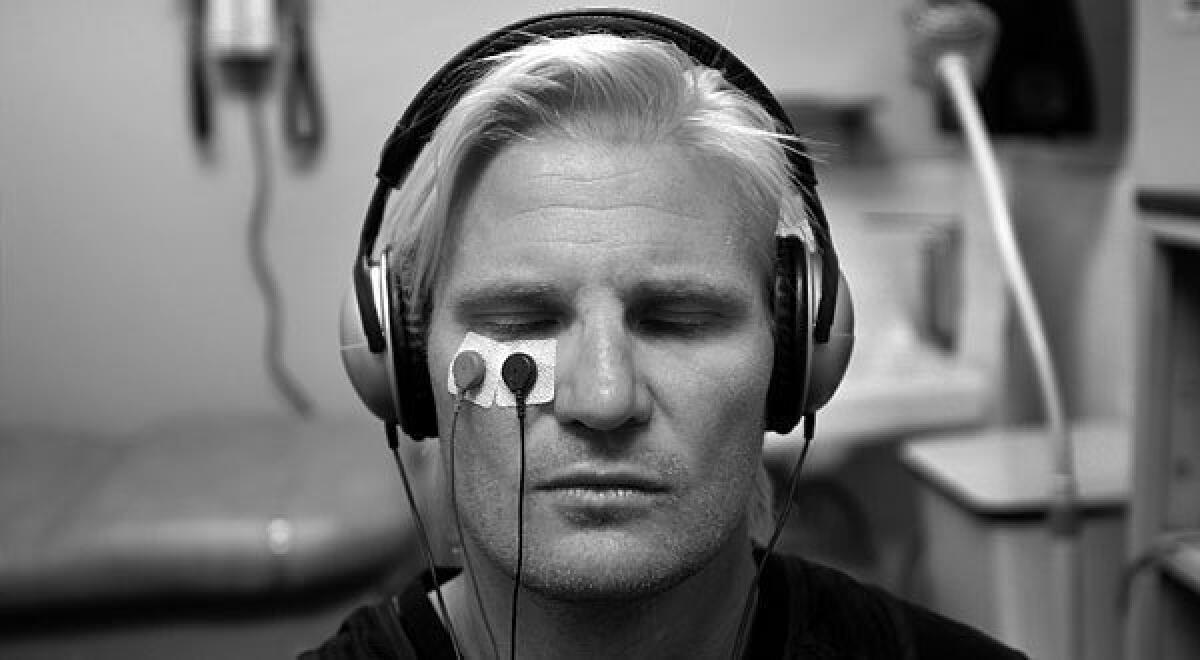

He spotted a flier on the wall. It offered an alternative. He could volunteer as a test subject for a pioneering treatment. Veterans would be asked to throw themselves into their single worst memory, to relive every sight and sound with the help of full-immersion goggles and earphones ... and then do it again ... and again ...

"How do I get started?" he asked.

Warren seeks solace on the dock overlooking Newport Bay, where he would walk daily. Anxiety, dread and guilt followed him home from war.

RELIVING HIS WORST DAY

Marya Schulte's closet-size office sits inside a maze of colorless corridors in the VA hospital's mental-health wing. To add warmth, she has decorated it with gentle black-and-white photographs of Manhattan architecture.

A padded curtain hangs over a rear door, to muffle the bellowing of the Vietnam vets who meet next door. The VA has given her a converted storage room for a five-year study in the use of virtual reality in Prolonged Exposure Therapy.

It is one of dozens of sites offering the treatment around the country, using simulations developed at the USC Institute for Creative Technologies.

For a generation raised on Game Cubes, it promises a way to lure reluctant soldiers into therapy. But it can be brutal for everyone involved. A patient must descend into his worst memory; a therapist must steer him into its grip, again and again.

It's March 2012. Warren studies the therapist's face, youthful and unlined. She hasn't experienced battle except in the stories of her patients. He wonders if she will understand.

She helps him adjust the earphones and visor. She hands him a joystick.

In the simulation, he sits in the passenger seat of a Humvee, looking over the hood. Before him, a paved road with a double yellow line runs through the desert.

The joystick moves him forward. Here and there, palm trees and Iraqi homes appear and disappear. He can turn his head and see another soldier, the driver, in the seat beside him.

Can he trust his memory? He is anxious to get it right.

Warren participates in research into post-traumatic stress disorder at the VA hospital in Long Beach.

Don't worry, she tells him. Narrate what happened on Nov. 25, 2006.

"What do you hear?"

An explosion. Or maybe not. He can't be sure. All he knows is that he wakes to the sound of his own screaming.

Schulte hits buttons. His seat vibrates. His simulated windshield cracks. He sees black smoke billowing from the road.

"What does it feel like in the Humvee?"

Unbearably hot — a furnace. His face blisters. His neck burns. His wrists are singed as he forces open the heavy door and scrambles outside.

The simulation is imperfect. It cannot put him outside the truck. To relive that part, he closes his eyes.

Schulte hits buttons. He hears gunfire and chopper blades and radio chatter. More than the visuals, the sounds take him back five years and across 7,000 miles. Now his heart is racing.

"What do you see?"

Scotty struggling to escape the truck.

"What does he look like?"

A fireball.

"What happens next?"

He races toward his friend but is stopped by the wall of flame. For the barest instant he thinks, if I go in, what will I look like afterward?

"What happens next?"

Scotty is out and running toward a canal and Warren commands him to drop, and then he's leaning over Scotty in the dirt and pounding uselessly at the flames and then crawling away, defeated, until the medic arrives.

He feels helpless and worthless. What kind of soldier quits on his brother?

"I have nothing to help him with," he tells Schulte. "I should have come up with something."

The simulations last 40 minutes. He feels raw. He thanks Schulte and weeps on the freeway drive home.

Warren can't shake the feeling that somehow, some way, Stephenson blames him for what happened. Because they don't talk about the bomb, Warren can't be sure.

If anyone asks, Stephenson will say Warren saved his life. It's the same thing Warren's mother always tells him: Scotty was lucky you were there.

Stephenson, left, was known in the Army as "Oreo." Warren was "The Duke." In civilian life, they lived in different states, but their friendship remained strong.

Warren doesn't believe it. His memory has bent and twisted in strange, punishing ways. The chaos of that day has congealed into a narrative of his own incompetence and weakness.

He isn't sure he will return for another session with Schulte.

Then he thinks: What's the alternative? Pills, pot, blackout drinking? A lifetime of hiding in his darkened apartment?

He returns to Schulte's office, explaining that he feels no better. His flashbacks have not softened. The crushing thing in his midsection has not gone away.

That's normal, she says. She compares his war experience to a book that keeps popping open, no matter how hard he tries to close it. Things will get worse before they get better. He puts on the visor. He grips the joystick. He goes down the road. The windshield cracks. The smoke churns.

He closes his eyes. His best friend burns.

"I'm not who I thought I was," he tells Schulte. "I didn't act how I thought I would act."

Why can he summon so many details of that day — the feel of the dirt, the smell of the blood — but not the image of Scotty's face as he was writhing? Maybe it is his brain's way of protecting him.

He enters the little room. He goes down the road. His best friend burns.

"Did you plant the IED?" she asks. "Did you set the vehicle on fire?"

Buried details are resurfacing. Now, he can feel the intensity of the heat pulsing from the Humvee. He remembers the sensation of his face melting when he gets within 10 feet of the truck. Remembers that his lips blister when he gets within 5 feet.

Slowly, he realizes that during the many times he's recounted the story — including the first few times he told it to Schulte — he omitted crucial details. It is as if he's forgotten everything that doesn't serve the story of his guilt.

Now he remembers that the bomb blasts him into the roof of the truck and tears off his Kevlar helmet.

That his ears are leaking cerebrospinal fluid.

That his own fire-dousing blanket is aflame.

That the interval between the bomb and the arrival of help feels like an hour, but is really only a minute.

That by ordering Stephenson to the ground, he might have saved him from scrambling blindly into the canal and drowning.

She asks him to imagine the situation in reverse — he is burning, and Scotty can't help.

Warren considers it. As a child in an evangelical Christian household, he was raised with a strong awareness of a God forever disappointed by his shortcomings. One day God would ask for a sacrifice, he knew, and he'd have to be big enough to give it.

Would you blame Scotty, if the roles were reversed?

That's different. God expects me to be perfect.

During his seventh session in the little room, Schulte asks:

"What if you do run into the burning Humvee?"

Warren thinks about his buddy laden with 120 pounds of armor, knives, bulging pouches, ammunition and equipment.

He thinks about his own bulky armor.

He thinks about his disorientation and pain, and the chaos of the truck's interior.

And he realizes what would happen if he somehow got inside through the flames. He would prevent Stephenson from escaping.

"We would have both died."

In the months after his therapy ends in the spring of 2012, Warren realizes that confronting Nov. 25, 2006, might be only the beginning of healing. One night he pounds tequila and wakes up in the ER. One night police throw him in the drunk tank.

One night he stands in the center of the Dana Hills High School football field, bathed by floodlights, an honored veteran performing the coin toss before his brother Logan's final football game, and he knows the moment would have been impossible a year ago, even if he still needs the comfort of a Clonazepam in his pocket.

He is starting to attempt other things that were once inconceivable, like weekend trips with friends.

He knows he will have to confront other terrible memories — such as the day his platoon called in rockets on the enemy and he found a dead girl and her dead mother amid the rubble.

He is crying when he asks his mother, "What did I accomplish over there?" He is still crying after she repeats the answer she always gives: that he saved Scotty, and it is enough.

Warren adjusts an American flag during a celebration at his parents' Laguna Niguel home after his graduation from Vanguard University. (Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

Warren, left, embraces his brother Logan at the conclusion of Logan's last high school football game.

At an "Honor the Valor" benefit football game, Warren salutes with Harry Clew, 90, of Dana Point, who spent 15 months as a prisoner of war in World War II.

Contact the reporter | Follow Christopher Goffard (@LATChrisGoffard) on Twitter

Contact the photographer | Follow Rick Loomis (@RickLoomis) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

About this story:Times staff writer Christopher Goffard met Jonathan Warren a year ago and interviewed him dozens of times. He also spoke at length with Warren's mother and his best friend, Scott Stephenson, and reviewed Warren's military records and journals he kept while deployed in Iraq.

With Warren's consent, psychologists Marya Schulte and Rachel Robertson detailed his treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. For background on prolonged exposure therapy using virtual reality, Goffard interviewed Christopher Reist, chief of research at the Department of Veterans Affairs hospital in Long Beach; Michael Hollifield, director of the hospital's traumatic stress program; and Albert "Skip" Rizzo of the USC Institute for Creative Technologies.

The description of the events of Nov. 25, 2006, is based on accounts from Warren, Stephenson and squad leader Lewis Henderson.

Additional credits: Video Producers, Spencer Bakalar and Liz O. Baylen | Web Producers, Armand Emamdjomeh and Evan Wagstaff | Digital Design Director, Stephanie Ferrell

Also by Christopher Goffard and Rick Loomis

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.