State fails to keep track of dangerous materials shipped for disposal

On paper, California’s rules on handling hazardous waste are among the nation’s strictest. But there are huge holes in the system.

- Share via

Year after year the trucks rolled in, dumping loads of sewage sludge and contaminated dirt at a soil-recycling plant in this tiny desert community.

Thousands of deliveries were dutifully recorded in a state database. Anyone who checked it would have seen that the plant had no state permit to accept hazardous waste.

Yet the dumping went on for seven years — because state regulators either did not look at their own records or did not act on the information. The waste piles grew, rising 40 feet above the Coachella Valley floor. The stench worsened too.

Eventually, noxious odors swept over Saul Martinez Elementary School, more than a mile away. Children vomited. Teachers gasped for breath. Even then it took a storm of publicity and pressure from a U.S. senator before regulators stopped the dumping in 2011.

"It was just blatant negligence," said Celia Garcia, then a teacher at the school, where two of her children were students.

The episode is emblematic of California's chronic failure to keep track of thousands of tons of dangerous chemicals and toxic metals shipped for disposal on the state's roads and railways, a Times investigation found.

On paper, California's rules on handling hazardous waste are among the strictest in the nation. The cornerstone is a "cradle to grave" tracking system designed to protect people and the environment by documenting the whereabouts, at every step, of 1.7 million tons of hazardous waste shipped for disposal annually.

From dry cleaners to heavy manufacturers, businesses that generate waste must report every load they ship. Disposal and treatment facilities must record the waste's safe arrival. And the state Department of Toxic Substances Control is required to track every ton to make sure it isn't dumped illegally along the way.

That's how the system is supposed to work. But it doesn't.

There are huge holes in the department's database. Regulators make only limited use of what information is available. And the system does not automatically flag potential problems.

The result: Regulators lose track of large quantities of toxic chemicals and cancer-causing metals.

The department cannot account for 174,000 tons of hazardous material shipped for disposal in the last five years, a Times analysis found. That's more than 23,000 truck or tanker loads.

The state database shows they were shipped but gives no indication they arrived at their intended destinations — many of which are out of state.

These so-called lost loads include more than 20,000 tons of lead, a neurotoxin; 520 tons of benzene, a carcinogen; and 355 tons of methyl ethyl ketone, a flammable solvent some in the industry call "methyl ethyl death."

Nearly 60% of those loads are classified as hazardous by federal standards — meaning the waste is so potentially harmful it must be regulated in all 50 states. The rest falls under California's stricter standards.

Top regulators acknowledge flaws in the tracking system but insist that public health is not threatened. They say they are confident that missing shipments find their way to authorized disposal sites. But, they admit, they can't be sure.

"We don't know," said Debbie Raphael, director of the department, which has a $189-million budget and about 900 employees. "It's a question mark."

Raphael said the information gap "is concerning, absolutely." But she and other officials said that if a significant amount of toxic waste was being dumped illegally, they would hear about it through complaints from the public, reports from local authorities and other channels.

I understand that it seems somewhat ridiculous in an electronic age that we are still working with paper."— Rick Brausch, a chief of California's hazardous waste management program

In any case, generators are legally responsible for ensuring that their waste is disposed of properly and alerting the agency when they think it hasn't been. And local and state inspectors periodically check businesses' records for proof of proper disposal.

"I do not believe that Californians are at risk," Raphael said.

Some legislators and environmental advocates disagree.

"I think it's completely unacceptable that California is unable to track waste from where it is generated to its disposal site," said Assemblyman Luis Alejo (D-Salinas), chairman of the Assembly's committee on environmental safety and toxic materials.

It can be difficult to link illnesses to hazardous waste because those who have been exposed might not know it; also, symptoms can take years to develop and can be ascribed to other causes.

But even a small amount of errant waste can create "a very big public health impact," said W. Bowman Cutter, an associate professor in the environmental analysis program at Pomona College, who has studied the state's hazardous waste system.

"These are all wastes that have been shown to be harmful to health directly," he said, referring to the most dangerous compounds, including lead and benzene.

Federal Express, Amazon and the U.S. Postal Service can follow the movement of millions of items big and small, from shipping dock to front door. Workers can punch a few buttons on hand-held devices and enter enough information to track packages electronically.

By contrast, California's hazardous-waste regulators rely on pen, paper and snail mail.

When toxic chemicals are shipped for disposal, the businesses that generated the waste fill out a manifest by hand or with a typewriter and send a copy to a post office box in Sacramento.

The manifest consists of an original and five carbonless copies. The waste generator keeps the bottom one, the faintest, and sends the rest on trucks with the haulers.

The copies on top — which are easier to read — are given to disposal or treatment facilities. They are supposed to ensure that the loads delivered match what was shipped. If they do, the facilities accept the loads and send their copies of the manifests to the state.

In theory, the state then matches the "cradle" and "grave" copies and enters the information into the database, creating a seamless record of every shipment.

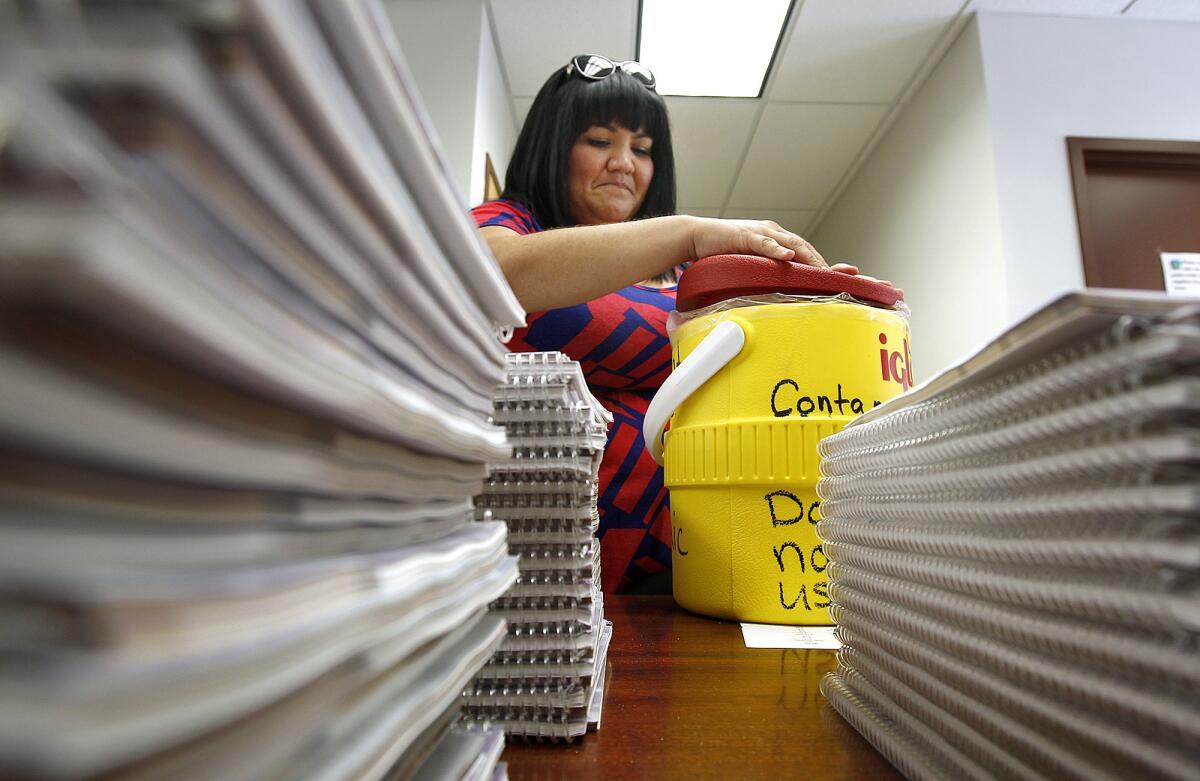

A worker at a Waste Management facility in Kettleman City takes inventory of hazardous materials in 2009. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

In reality, the system is undermined by illegible paper forms.

Because they often can't read what's on the copy sent by the generator, the state contractors who perform data entry simply do not enter that information for most shipments.

Seven years ago, regulators told them to stop trying.

The result is that officials do not routinely verify that the waste received by treatment and disposal facilities is the same type and amount as was shipped.

The Times' analysis also found that the disposal manifest, which documents that a shipment was received and processed appropriately, is missing for about 1% of all loads.

In a state as large as California, that adds up — to 174,000 tons of missing waste.

With no evidence of a load's ultimate delivery, the state's practice is to try to decipher from the generator copy what was shipped. Once that information is entered into the database, the state acts on the assumption that the missing shipments were disposed of safely.

But in most cases, no one investigates what actually happened to the waste.

"We don't know where it is," said one agency scientist who spoke on condition of anonymity, citing a fear of retribution. "We know the cradle, but we don't know where the grave is."

The Times attempted to do what the state typically does not: It contacted half a dozen major disposal facilities, as well as several businesses associated with thousands of loads for which disposal information is missing from the database. Reporters sent spreadsheets of manifests and asked disposal plants and businesses to account for the waste.

Some of it arrived and was properly disposed of, The Times found — it simply was not entered into the database because of clerical errors or for other reasons. But a significant amount never got to where it was supposed to go.

The database indicates, for instance, that 96 of the missing loads had been headed to Chemical Waste Management's facility in Kettleman City, one of two active landfills in California licensed to accept hazardous waste.

Chemical Waste spokeswoman Jennifer Andrews said she could account for 38 of those loads. But 58 never arrived, she said. Those shipments included 20 tons of lead and 14 tons of arsenic, records show.

Celia Garcia, who grew up in Mecca, opens a container with a sample of the odor from Western Environmental, a waste facility, during a visit to Saul Martinez Elementary School. (Christina House / For the Times) More photos

Another missing load came from Al's Plating in South Los Angeles. The company reported sending nearly a ton of waste to World Resources Co. in Arizona. The load never got there, according to Ray Corcoran, a World Resources vice president. Al's Plating went out of business, and the whereabouts of the Arizona-bound waste is unknown.

Most of the other unaccounted-for loads sent to the Arizona facility did arrive, even though the database does not reflect it, staffers there said.

Four other facilities, in California, Nevada and Utah, ignored or declined The Times' requests for information on thousands of missing loads.

Raphael said she inherited the tracking system when she took over the department in 2011, but that she takes responsibility for correcting its flaws.

"I'm not saying we're at the gold standard or satisfied with where we are," she said. She added that the department is looking to improve the database and upgrade its crash-prone computer system.

A year and a half ago, in response to the Mecca episode, the department assigned an employee to scour the database for other disposal sites accepting waste without permits. None was found, and the staffer is now mining the data for signs of unlicensed waste-transporters.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency plans to introduce a fully electronic manifest system that should fix the paper-records problem, department officials said. But that won't be until 2015, at the earliest.

"I understand that it seems somewhat ridiculous in an electronic age that we are still working with paper," said Rick Brausch, chief of the hazardous waste management program.

California's Hazardous Waste Control Act of 1972 was seen as a model for the nation.

The law was prompted by the growing realization that hazardous waste was a public health risk, and set guidelines for handling and tracking waste. A similar federal law was passed four years later.

For decades, California's program has been troubled. In 1983, the auditor general found that the state "does not adequately protect the public and environment," citing its failure to police toxic-waste disposal. In 1986, federal officials briefly stripped California of its power to regulate hazardous waste.

Los Angeles County Fire Department hazardous materials specialists Mario Benjamin, left, and Nancy Parson respond to a call in Whittier. (Christina House / For The Times) More photos

The state created its "cradle to grave" tracking system in 1990. Three years later, officials inadvertently entered 300,000 manifests with duplicate ID numbers, wreaking havoc on the system, the Wall Street Journal reported in 1997.

All the while, regulators had to contend with rogue generators and haulers of hazardous waste. A major problem is that legal disposal is costly — fees for a 55-gallon drum of waste containing benzene or metal-plating waste can run $400 or more, not including transportation.

Some businesses and haulers dump waste down drains, on roadsides or in public landfills, skirting the tracking system altogether.

State officials say that once a load has been documented in a manifest it is less likely to be disposed of illegally. But The Times found many examples in which that happened.

In Santa Fe Springs, a stockpile of drums containing used oil and a soup of other hazardous wastes was parked in a small warehouse, across Washington Boulevard from a residential neighborhood.

Sal Garcia, the hauler, had picked up the waste from various businesses that paid him to dispose of it properly, officials said.

Instead, he placed the drums in storage. It came to light only after someone tipped off the EPA — local officials said the warehouse owner told them it was the hauler's estranged wife.

Tracing the sources of the waste was difficult because Garcia had peeled the labels off most of the containers, said Fernando Florez, head of investigations for the Los Angeles County Fire Department's haz-mat division.

Investigators traced some of the waste to Astro Aluminum Treating, a South Gate company that treats aerospace components for such major manufacturers as Boeing and Raytheon.

Astro paid a $12,000 fine and improved its waste-handling processes, Florez said. The company did not respond to requests for comment.

Florez said Astro "should have known" that the substances had not been disposed of properly, because it never received copies of manifests from disposal facilities.

In late 2010, teachers and children at Saul Martinez Elementary School were evacuated from the school, overwhelmed by noxious odors from Western Environmental. (Christina House / For The Times) More photos

State officials might have known too — if their tracking system were able to alert them when waste goes astray.

Garcia has not been charged, according to an EPA spokeswoman. Efforts to reach him for comment were unsuccessful.

In another case, the same waste was abandoned twice in locations 50 miles apart over the course of six years.

Trailers of toxic waste that included spent aerosol containers, used motor oil and mercury — which can damage the brain, kidneys and lungs — were abandoned in Hayward in Alameda County in 2004, according to law enforcement officials.

When the waste was discovered, the alleged dumper, Jose Sosa, told authorities he would dispose of it properly but did not, officials said.

"Some of it ended up in my county several years later," said David Irey, a San Joaquin County deputy district attorney.

Police in the town of Ripon found 245 drums from the same load in an abandoned trailer at a truck stop in 2010. Sosa told authorities he'd left the rig after his trucking business failed.

The waste was ultimately disposed of properly, a spokesman for the state agency said.

Sosa could not be reached for comment. The state has sued to strip him of his license to haul hazardous waste.

State officials had every reason to know that there was a problem at Western Environmental Inc.'s soil-recycling plant in Mecca, on land owned by the Cabazon Band of Mission Indians.

In 2004, the department's criminal investigations branch received a complaint that the plant was operating without a state permit, but the shipments continued.

One of the agency's own employees later reported that the facility was receiving "large amounts of dirt and other solid waste," and that there was no record it had been granted a state permit.

The employee contacted the agency's legal counsel, department records show, but still the dumping continued.

Then, in December 2010, students and teachers at Saul Martinez Elementary School got sick.

"It was maybe an hour into the school day, and the odor was not relenting," said Celia Garcia, the former teacher at the school.

"Even with the doors closed, even with the windows closed, you could still smell it in the classroom. I remember some of the students complaining that their little heads were hurting, their tummies were hurting because of that smell. It was just making everybody sick."

After dumping a load of waste, a truck exits the Chemical Waste Management Company in Kettleman City. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Liria Vargas remembers feeling sick to her stomach that day, the first of many over several months when odors engulfed the heavily Latino community near Indio.

"My kids had to stay indoors all the time," Vargas said. "It was bad, really bad."

Environmental regulators traced the odor to the plant. The EPA stepped in after news accounts appeared in the Press-Enterprise of Riverside and the Desert Sun in Palm Springs and U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.) demanded action.

When state regulators searched their database, they found that 9,719 loads, amounting to more than 160,000 tons of waste, were shipped to Mecca in 2009 and 2010 alone. Project managers at the agency had authorized the shipment of metal sludge, empty pesticide cans and other waste from construction sites in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

"Wow, that's pretty awful," Raphael said, recalling her reaction at the time.

In May 2011, the EPA ordered the company to stop accepting hazardous waste and to reduce and cover the soil piles. The state agency ordered businesses to stop sending waste to Mecca.

In a report in August of that year, state officials faulted their own agency for failing to have a policy on the transport and disposal of hazardous waste on Indian lands and for weaknesses in internal communications.

They also noted that they had failed to monitor their own database.

"There wasn't anybody taking a look at it to say, 'Where are the red flags?' " Raphael said recently. "Therefore, nobody was paying attention to them."

Follow Jessica Garrison (@latimesjessicag), Ben Poston (@bposton) and Kim Christensen (@kchristensenLAT) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

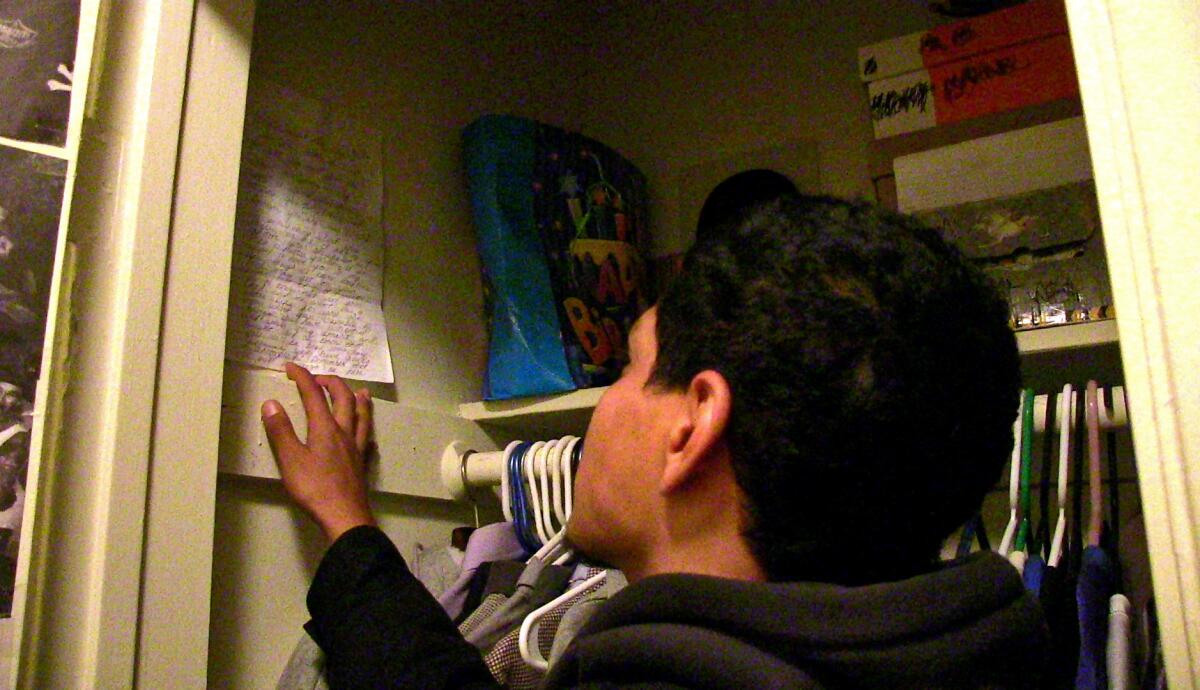

Bernstein High football players earn letters — of parents' love

I love you. And you're the most important thing in my life. You know I would die for you."

A hostile school environment, but 'these are not bad kids'

No one on this campus will be threatened by other students."

In Karachi, crime leaves few families untouched

It's always in the back of my mind. But at least I'm not so afraid to go outside now."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.