Voters approve Proposition 8 banning same-sex marriages

- Share via

UPDATE: Voters approve Proposition 8 banning same-sex marriages. With more than 95% of the vote counted, the measure leads 52.1% to 47.9%.

A measure to once again ban gay marriage in California led Tuesday, throwing into doubt the unions of an estimated 18,000 same-sex couples who wed during the last 4 1/2 months.

FOR THE RECORD:

Proposition 8: A chart in some editions of Wednesday’s Section A that contained vote results for Proposition 8, the measure to ban gay marriage in California, said the figures were the latest as of 12:25 p.m. Pacific time. They were the latest as of 12:25 a.m. —

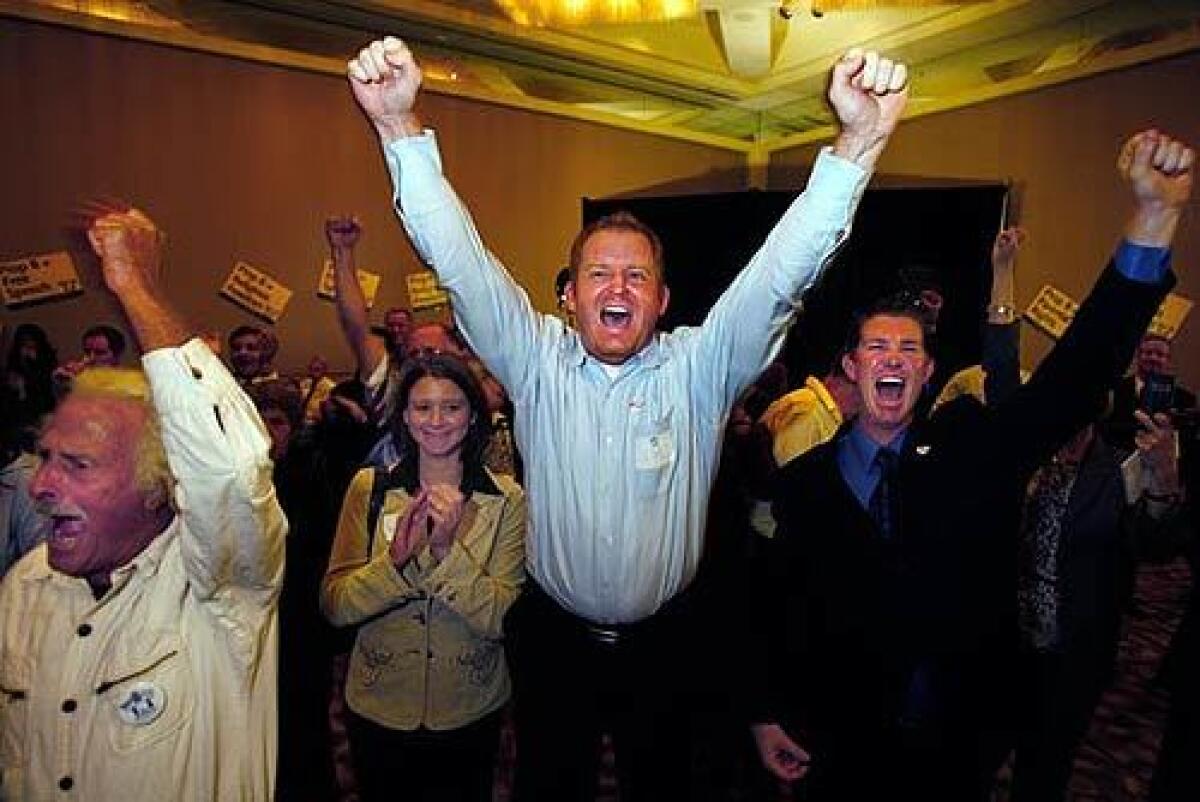

As the measure, the most divisive and emotionally fraught on the state ballot this year, took a lead in early returns, supporters gathered at a hotel ballroom in Sacramento and cheered.

“We caused Californians to rethink this issue,” Proposition 8 strategist Jeff Flint said.

Early in the campaign, he noted, polls showed the measure trailing by 17 points.

“I think the voters were thinking, well, if it makes them happy, why shouldn’t we let gay couples get married. And I think we made them realize that there are broader implications to society and particularly the children when you make that fundamental change that’s at the core of how society is organized, which is marriage,” he said.

But in San Francisco at the packed headquarters of the No on 8 campaign party in the Westin St. Francis Hotel, supporters of same-sex marriage refused to despair, saying that they were holding out hope for victory.

“You decided to live your life out loud. You fell in love and you said ‘I do.’ Tonight, we await a verdict,” San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom said, speaking to a roaring crowd. “I’m crossing my fingers.”

Elsewhere in the country, two other gay marriage bans, in Florida and Arizona, were well ahead. In both states, laws already defined marriage as a heterosexual institution. But backers pushed to amend the state constitutions, saying that doing so would protect the institution from legal challenges.

Proposition 8 was the most expensive proposition on any ballot in the nation this year, with more than $74 million spent by both sides.

The measure’s most fervent proponents believed that nothing less than the future of traditional families was at stake, while opponents believed that they were fighting for the fundamental right of gay people to be treated equally under the law.

“This has been a moral battle,” said Ellen Smedley, 34, a member of the Mormon Church and a mother of five who worked on the campaign. “We aren’t trying to change anything that homosexual couples believe or want -- it doesn’t change anything that they’re allowed to do already. It’s defining marriage. . . . Marriage is a man and a woman establishing a family unit.”

On the other side were people like John Lewis, 50, and Stuart Gaffney, 46, who were married in June. They were at the San Francisco party holding a little sign in the shape of pink heart that said, “John and Stuart 21 years.” They spent the day campaigning against Proposition 8 with family members across the Bay Area.

“Our relationship, our marriage, after 21 years together has been put up for a popular vote,” Lewis said. “We have done what anyone would do in this situation: stand up for our family.”

The battle was closely watched across the nation because California is considered a harbinger of cultural change and because this is the first time voters have weighed in on gay marriage in a state where it was legal.

Campaign contributions came from every state in the nation in opposition to the measure and every state but Vermont to its supporters.

And as far away as Washington, D.C., gay rights organizations hosted gatherings Tuesday night to watch voting results on Proposition 8.

“I am nervous,” Human Rights Campaign President Joe Solmonese said from a brewery in the nation’s capital. “This is the biggest civil rights struggle for our movement in decades. . . . The outcome weighs incredibly heavily on the minds of every single person in the room.”

Eight years ago, Californians voted 61% to define marriage as being only between a man and a woman.

The California Supreme Court overturned that measure, Proposition 22, in its May 15 decision legalizing same-sex marriage on the grounds that the state Constitution required equal treatment of gay and lesbian couples.

Opponents of Proposition 8 faced a difficult challenge. Bob Stern, president of the Center for Governmental Studies, said California voters “very, very rarely reverse themselves” especially in such a short time. Both sides waged a passionate -- and at times bitter -- fight over whether to allow same-sex marriages to continue. The campaigns spent tens of millions of dollars in dueling television and radio commercials that blanketed the airwaves for weeks.

But supporters and opponents also did battle on street corners and front lawns, from the pulpits of churches and synagogues and -- unusual for a fight over a social issue -- in the boardrooms of many of the state’s largest corporations.

Most of the state’s highest-profile political leaders -- including both U.S. senators and the mayors of San Francisco, San Diego and Los Angeles -- along with the editorial pages of most major newspapers, opposed the measure. PG&E, Apple and other companies contributed money to fight the proposition, and the heads of Silicon Valley companies including Google and Yahoo took out a newspaper ad opposing it.

On the other side were an array of conservative organizations, including the Knights of Columbus, Focus on the Family and the American Family Assn., along with tens of thousands of small donors, including many who responded to urging from Mormon, Catholic and evangelical clergy.

An early October filing by the “yes” campaign reported so many contributions that the secretary of state’s campaign finance website crashed.

Proponents also organized a massive grass-roots effort. Campaign officials said they distributed more than 1.1 million lawn signs for Proposition 8 -- although an effort to stage a massive, simultaneous lawn-sign planting in late September failed after a production glitch in China delayed the arrival of hundreds of thousands of signs.

Research and polling showed that many voters were against gay marriage, but afraid that saying so would make them seem “discriminatory” or “not cool,” said Flint, so proponents hoped to show them they were not alone.

Perhaps more powerfully, the Proposition 8 campaign also seized on the issue of education, arguing in a series of advertisements and mailers that children would be subjected to a pro-gay curriculum if the measure was not approved.

“Mom, guess what I learned in school today?” a little girl said in one spot. “I learned how a prince married a prince.”

As the girl’s mother made a horrified face, a voice-over said: “Think it can’t happen? It’s already happened. . . . Teaching about gay marriage will happen unless we pass Proposition 8.”

Many voters said they had been swayed by that message.

“We thought it would go this way,” Proposition 8 co-chair Frank Schubert said. “We had 100,000 people on the streets today. We had people in every precinct, if not knocking on doors, then phoning voters in every precinct. We canvassed the entire state of California, one on one, asking people face to face how do they feel about this issue.

“And this is the kind of issue people are very personal and private about, and they don’t like talking to pollsters, they don’t like talking to the media, but we had a pretty good idea how they felt and that’s being reflected in the vote count.”

Jessica Garrison, Cara Mia DiMassa and Richard Paddock are Times staff writers.

richard.paddock

@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.