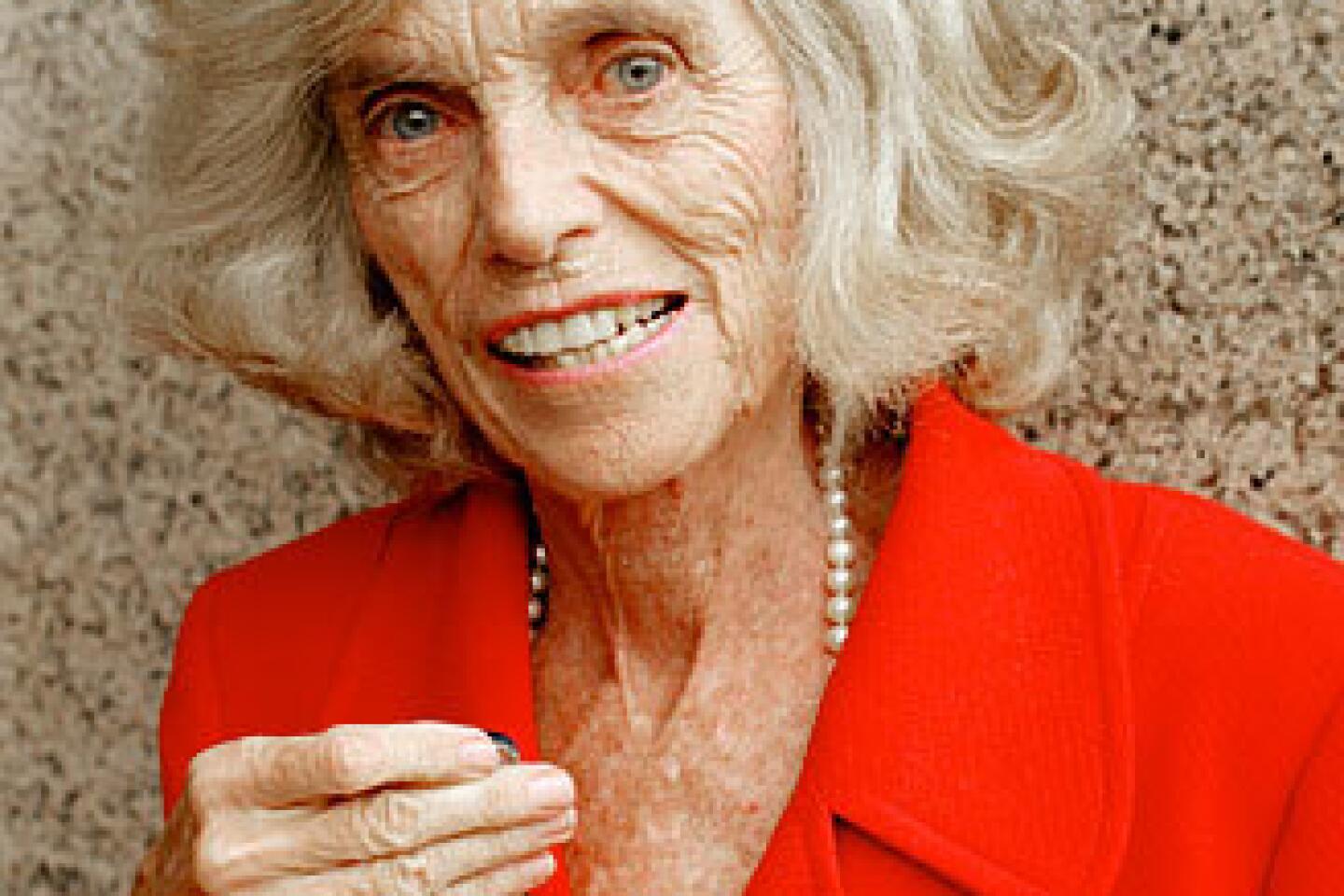

Eunice Kennedy Shriver dies at 88; Special Olympics founder and sister of JFK

- Share via

Women in mid-20th century America were not yet welcome on the grand political stage, but Eunice Kennedy Shriver -- a daughter of uncommon privilege who defined herself as a mother above all -- didn’t much care. As the younger sister of President Kennedy and with a family foundation behind her, she became an unstoppable advocate for the mentally disabled.

In the early 1960s, Shriver pushed mental retardation onto the national agenda. Her brother Robert, who was JFK’s attorney general, once joked: “President Kennedy used to tell me, ‘Let’s give Eunice whatever she wants so I can get on with the business of government.’ ”

Shriver’s advocacy for those with special needs would never end once it took root in sports. In 1968, she founded the Special Olympics, the athletic competition for the mentally disabled.

During the first games, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley told her: “Eunice, the world will never be the same.”

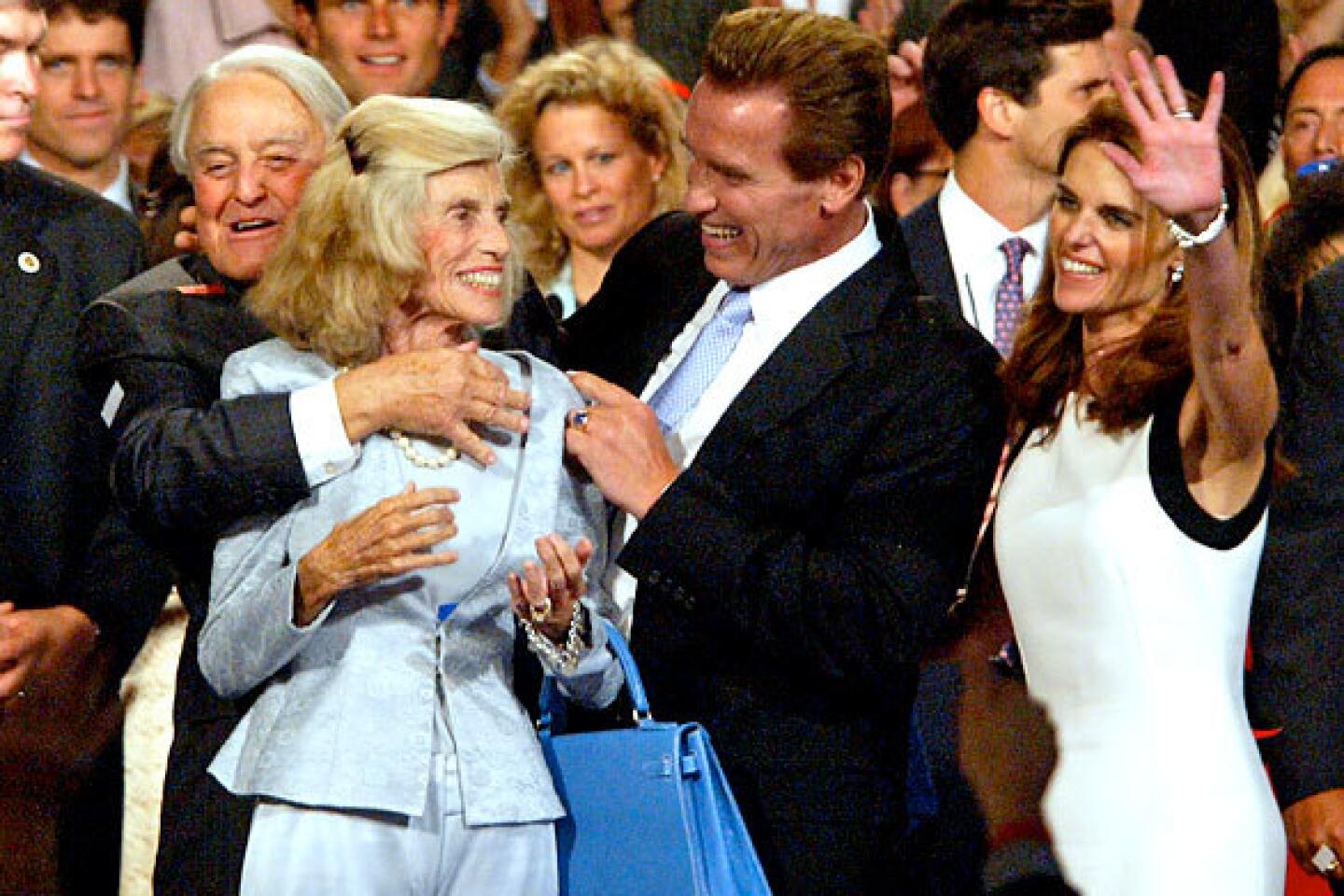

Shriver, who was also the sister of Sen. Edward M. Kennedy and the mother of California First Lady Maria Shriver, died Tuesday at Cape Cod Hospital in Hyannis, Mass., her family said. She was 88.

In a speech last fall at the Women’s Conference in Long Beach, Maria Shriver said her mother had had several strokes.

Two days before she was hospitalized in November 2007, Eunice Shriver was honored for her work with the disabled at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston at an event organized by her children. That fall, she also had traveled to Shanghai to attend her final Special Olympics.

“Eunice was the light of our family,” Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger said of his mother-in-law in a statement. “She meant so much, not only to us, but to our country and to the world. She was a pioneer who worked tirelessly for social and scientific advances that have changed the lives of millions of developmentally disabled people all over the world.”

President Obama called Shriver “a champion for people with intellectual disabilities” and “an extraordinary woman who, as much as anyone, taught our nation -- and our world -- that no physical or mental barrier can restrain the power of the human spirit.”

Shriver’s unflagging support for the mentally disabled, who for generations were hidden in shame and secrecy in America, has been called the Kennedy family’s most important campaign and was considered a precursor to the larger disability rights movement.

“When the full judgment of the Kennedy legacy is made -- including JFK’s Peace Corps and Alliance for Progress, Robert Kennedy’s passion for civil rights and Edward Kennedy’s efforts on healthcare, workplace reform and refugees -- the changes wrought by Eunice Shriver may well be the most consequential,” U.S. News & World Report magazine said in a 1993 cover story.

Edward Shorter, author of “The Kennedy Family and the Story of Mental Retardation” (2000), said that “no family has done more than the Kennedys to change negative attitudes about mental retardation.”

The founding of the Special Olympics went a long way toward erasing long-held stigmas that the Kennedy family knew well because Eunice had a sister who was mentally disabled. And the federal money that was unleashed resulted in research breakthroughs and a proliferation of educational programs.

President Kennedy enabled Shriver to help create both the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development and the President’s Committee on Mental Retardation. She made the issue so important to her brother that he reportedly left an emergency meeting during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 to receive the committee’s report.

More than 70% of the presidential committee’s 112 recommendations were eventually implemented, according to the U.S. News & World Report article on Shriver and the Kennedy family’s largely overlooked accomplishment. In the mid-1960s, more than $400 million a year in federal funds was appropriated to benefit the mentally disabled, which included hospital-improvement programs. More than twice that amount was being spent each year by states, local governments and private organizations, said a 1967 report by the president’s committee.

The advancements marked a “historic emergence of mental retardation . . . from isolation and public indifference,” the report said.

“If she had been a man, she certainly would have been a candidate for president,” Shorter told The Times. “Instead, she unleashed her tremendous executive energy on behalf of this cause and helped change history.”

Under her brother’s presidency, the history of mental retardation entered a new phase, according to Shorter.

“People with MR began to experience a new visibility and a growing acceptance,” he wrote. “This was an historic accomplishment: the ability to demonstrate one’s human worth despite the presence of a great handicap.”

On a more personal level, Shriver pushed for more than a year to reveal the closely guarded family secret that she was certain would dramatically help alter public opinion about the disabled. She wanted to disclose that the president’s sister Rosemary was mentally disabled.

In 1962, Shriver told the world about Rosemary’s condition in a Saturday Evening Post article. The headline read: “Hope for Retarded Children.”

Advocates for the mentally disabled point to the article and Shriver’s candor as a turning point that helped move mental disabilities from behind a curtain of ignorance.

The article pointed out that Rosemary was raised at home -- in an era when this was scorned -- and avoided mentioning the lobotomy that her father, Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., authorized in 1941 as a means of helping the mildly retarded Rosemary but worsened her condition. She lived most of her life in a private institution in Wisconsin, where Shriver was a frequent visitor, and died at 86 in 2005.

“I had enormous affection for Rosie,” Shriver told National Public Radio in 2007. “If I [had] never met Rosemary, never known anything about handicapped children, how would I have ever found out? Because nobody accepted them anyplace.”

Influenced by Rosemary’s ability at sports and her own inclination toward athletics, Shriver was drawn to the idea of physical activity as a way to benefit the mentally disabled.

“The world was full of people saying what mentally retarded people could not do,” her husband of 56 years, former Peace Corps Director Sargent Shriver, recalled some years ago. “She just didn’t believe that there were human beings who were as useless or hopeless, or whatever the right word might be, as the mentally retarded were thought to be 40 years ago.”

In 1961, Eunice Shriver turned Timberlawn, the family farm in Maryland, into a free day camp for mentally disabled children. She would get down in the dirt with campers, play in the sandbox, pitch softballs or teach them to swim. Shriver had them riding horseback and shooting bows and arrows.

“Nobody else’s mother was doing anything like that,” Maria Shriver said in the 1994 book “The Kennedy Women,” by Laurence Leamer. “It was always my mother following her own gut, going against the grain.”

When an idea was floated to stage a summer athletic festival for the mentally disabled, Eunice Shriver suggested broadening the concept to include participants from around the country. She had the Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. Foundation -- named for her oldest sibling, who was killed in World War II -- pay for them.

The first games, which featured only swimming and track and field events, were held in Chicago in the summer of 1968, just weeks after the assassination of Robert Kennedy.

In her opening address to about 1,000 competitors from 26 states and Canada, Shriver noted that the event was neither a spectacle “nor just for fun.” She wanted to prove that, through sports, these “exceptional children” could reach their potential.

Today the Special Olympics are played on a worldwide stage, with an estimated 2.5 million people from more than 150 countries taking part in hundreds of programs.

Athletes as young as 8 attend winter and summer games that have been staged every four years since the 1970s.

At the 2007 summer games in Shanghai, more than 7,200 athletes competed in 21 events that now include such sports as gymnastics, cycling and golf.

Shriver told NPR in 2007 that she continued to work for the mentally disabled “because it’s so outrageous, still. In so many countries. They’re not accepted. . . . So we have much to do.”

Eunice Mary Kennedy -- known within the family as “Puny Eunie” -- was born July 10, 1921, at home in Brookline, Mass.

The fifth of nine children of Joseph P. and Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy had chronic health problems all her life: Addison’s disease, an adrenal disorder that also plagued her brother John; stomach ulcers; colitis; and a tendency toward nervous exhaustion.

Yet Shriver’s fervent drive easily exhausted aides half her age and others around her.

She had “all that incredible energy,” Maria Shriver recalled in “The Kennedy Women.” “People think, ‘God, it would be such a horror if your mother had really great health. What would she have been like?’ ”

Eunice Kennedy attended Stanford University because her mother thought the mild California climate might improve her health.

After graduating in 1944 with a bachelor’s degree in sociology, she worked for the State Department reorienting American prisoners of war after World War II.

She also was a social worker at the Penitentiary for Women in Alderson, W.Va., and later worked for the Justice Department as coordinator of the National Conference on Prevention and Control of Juvenile Delinquency.

At a cocktail party in New York City in 1946, she met Robert Sargent Shriver Jr., a Navy veteran and Yale Law School graduate who worked on her father’s business staff.

They married in 1953 in front of 1,700 guests at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, bolstering what has been described as both an American and a Catholic aristocracy.

In 1958, her father asked Sargent and Eunice to run the foundation named for Joseph Jr. The senior Kennedy, reportedly tormented by the fate of his daughter Rosemary, was also looking for a cause to which the family name could be linked.

When JFK was elected president two years later, and Sargent Shriver was asked to run the Peace Corps, the foundation’s leadership fell squarely to Eunice.

In her hands, the cause of mental retardation “became an incandescent torch,” Shorter wrote in his book.

She couldn’t have accomplished more during JFK’s presidency if she had been given an official role, Eunice Shriver said in “The Kennedy Women” decades later.

“I was perfectly happy where I was,” she said. “And I think I just had a very wonderful relationship with my brother, and he was wonderful to this cause. I don’t say that blindly.”

Few avenues existed for the study of intellectual disabilities when the Kennedy foundation was established in 1946. One of the first centers the organization founded to diagnose and treat such disabilities is now known as St. John’s Child and Family Development Center in Santa Monica.

The foundation created a network of mental retardation research centers at medical schools at major universities, including Johns Hopkins, Harvard and Stanford.

It also established centers for the study of medical ethics at Harvard and Georgetown universities.

Eunice and Sargent Shriver’s marriage was widely considered the best in the big Kennedy clan.

Both were regular churchgoers committed to public service, and they made room for fun. When Sargent Shriver was U.S. ambassador to France from 1968 to 1970, his wife installed a trampoline on the residence lawn and often invited diplomats to bounce a bit.

As the mother of four sons and a daughter, Eunice Shriver thoroughly believed “in motherhood as the nourishment of life,” once writing that “it is the most wonderful, satisfying thing we can do.”

Son Mark was a member of the Maryland Legislature. Timothy has chaired the Special Olympics for more than a dozen years. Bobby is a Santa Monica city councilman and film producer. Anthony heads Best Buddies, which pairs college students with the mentally challenged. Maria, a former network news reporter, is also active in the Special Olympics.

Besides her children, Shriver is survived by her husband, 93, who has Alzheimer’s disease; brother Edward, who was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor in 2008; sister Jean Kennedy Smith;and 19 grandchildren.

Sen. Kennedy joined other family members who gathered at Shriver’s home for a private service Tuesday evening.

Information about the funeral and memorial services will be posted at eunicekennedyshriver.org, where online tributes are being accepted.

honored for her workhonored for her workShriver received many accolades during her lifetime, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, as well as the French Legion of Honor, the Lasker Award for public service and the Theodore Roosevelt Award of the National Collegiate Athletic Assn.

The younger generation of the Kennedy family often cited Eunice as the family member whom they looked up to most.

“She should have been president,” her nephew Bobby Kennedy said in the 1983 book “Growing Up Kennedy.” “She is the most impressive figure in the family. Most of my brothers, sisters and cousins would say they’d like to be like her.”

Mehren is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.