Community colleges’ crisis slows students’ progress to a crawl

- Share via

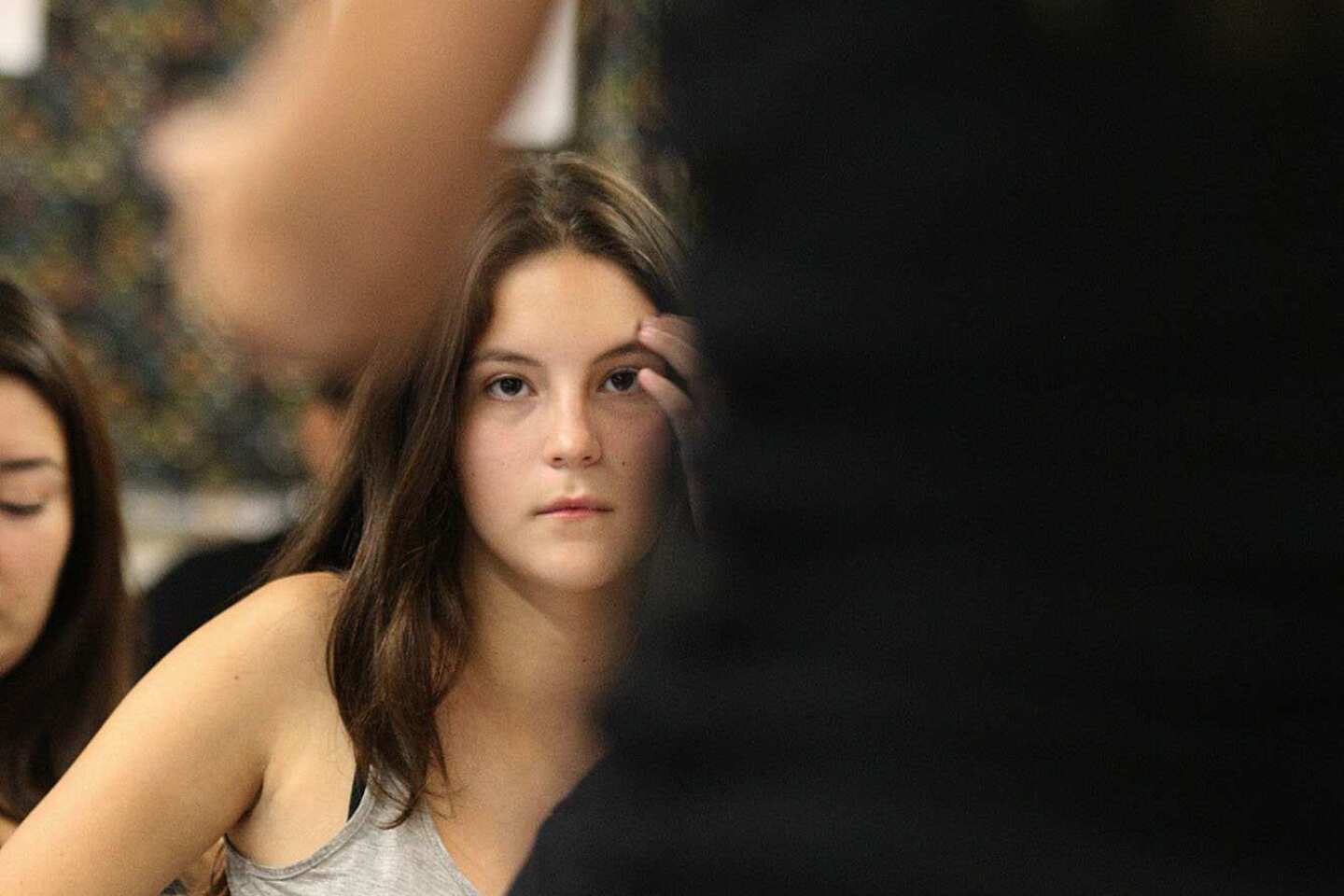

The first course Charity Hansen is taking as a freshman at Pasadena City College is a basic class on managing time, speaking up in discussions, setting ambitious goals and then going after them.

If only she could.

It’s the only class she managed to get this semester. No math. No English. No science.

Photos: Fading dreams: Higher learning slows to a crawl

“I can’t use what I’m being taught yet because I can’t get these classes,” said Hansen, a 19-year-old from Los Angeles who hopes one day to become a psychologist. “It’s frustrating.”

Hansen’s college education has stalled just as it is beginning. Like thousands of students in California’s community college system, she has been reduced to taking one class because there’s no room in other classes.

Instead of a full-time load of 12 units, some students are taking three units or even less.

Full coverage: California community colleges

Frustrated students linger on waiting lists or crash packed classes hoping professors will add them later. They see their chances of graduating or transferring diminishing.

It’s a product of years of severe budget cuts and heavy demand in the two-year college system. The same situation has affected the Cal State and UC systems, but the impact has been most deeply felt in the 2.4-million-student community college system — the nation’s largest.

At Pasadena City College, nearly 4,000 students who are seeking a degree or to transfer are taking a single class this fall. About 63% are taking less than 12 units and are considered part time. The school has slashed 10% of its classes to save money.

The lives of some community college students have become a slow-motion academic crawl, sometimes forcing them to change their career paths and shrink their ambitions.

Mark Rocha, president of Pasadena City College, said California’s once-vaunted community college system has never been in such a precarious state.

“It breaks our hearts,” he said. “The students who are here, we’re desperately telling them ‘Don’t drop out, don’t give up hope. We’ll get you through.’”

Since 2007, money from the state’s general fund, which provides the bulk of the system’s revenue, has decreased by more than a third, dropping from a peak of nearly $3.9 billion to about $2.6 billion last year.

Without enough money, course offerings have dropped by almost a quarter since 2008. In a survey, 78 of the system’s 112 colleges reported more than 472,300 students were on waiting lists for classes this fall semester — an average of about 7,150 per campus.

California ranks 36th in the nation in the number of students who finish with a degree or who transfer to a four-year university, according to a February report by the Little Hoover Commission. Many students drop out before completing even half of what is required to earn a typical associate’s degree, the report found.

Even for those who persevere, it can take years to graduate — well beyond the two years it once took.

Cinthia Garcia thought she was on the right track. She went straight from high school to El Camino College in Torrance with plans to transfer to a four-year university.

That was six years ago.

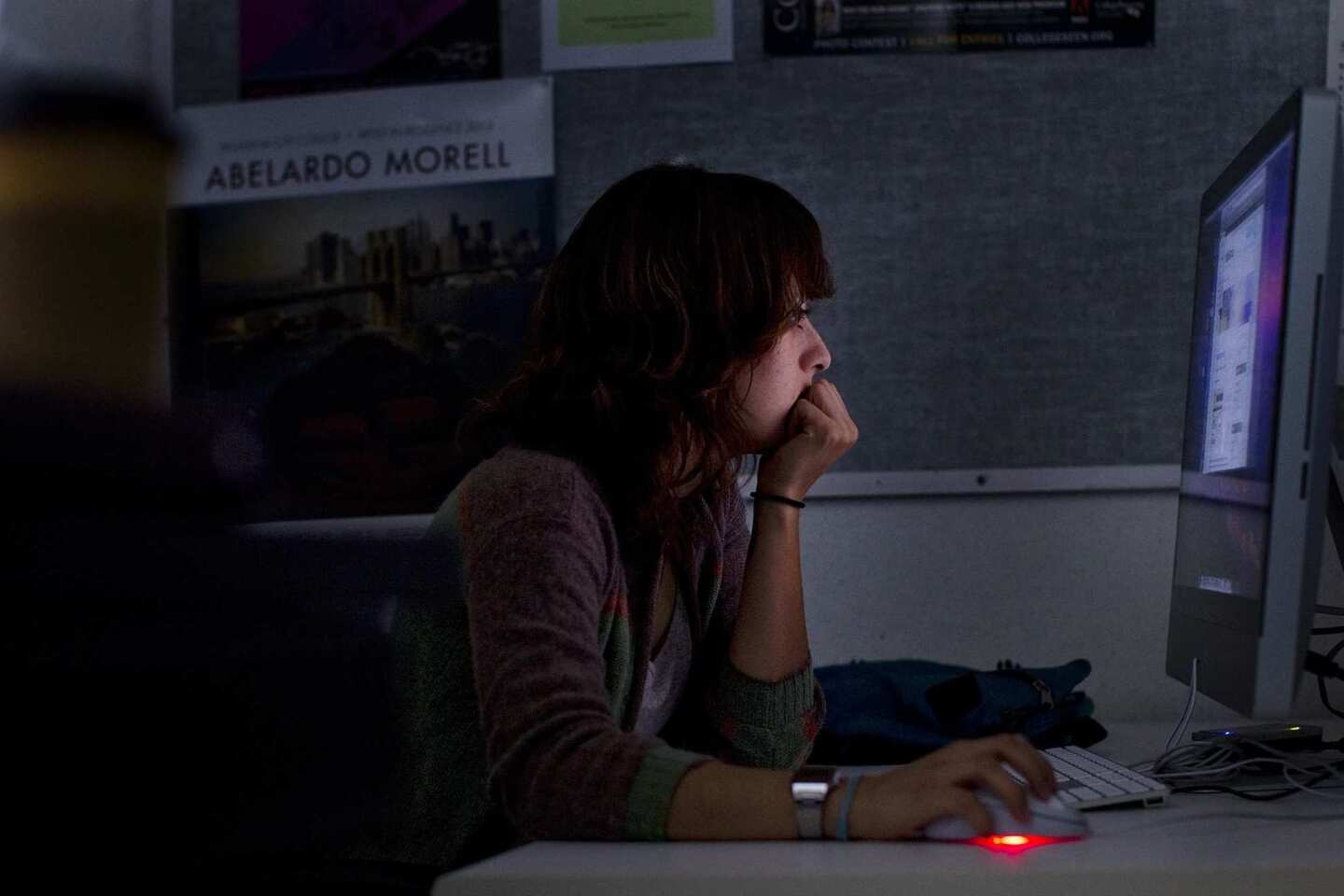

“I’ve been in school forever,” said the 24-year-old graphic design major from Compton.

At El Camino, she struggled to get classes, typically landing a spot in only two or three. The art department at El Camino began losing professors and Garcia decided she needed a change.

Pasadena City College, with a respected arts program, was appealing, so she moved to Los Angeles to be closer to school.

Still, she was unable to enroll in more advanced art classes, in part because they also were full.

She emailed every instructor in the art department, searching for a class. One responded. She told Garcia she would help her get the last seat in a Web design class. By then, the class was full, but a few days later, someone dropped the course and Garcia was in.

“All that for just one class,” she said, shaking her head.

The crowding has rippled through the school, causing long waits to see academic counselors — an important issue for many community college students who need advice on navigating the sometimes complex requirements to transfer to Cal State, UC or a private university.

At El Camino, Garcia said, the lines to see counselors were hours long. She’d make appointments weeks in advance, never seeing the same advisor twice, she said.

“I tried to do it on my own but I was only able to get so far,” she said. “Students are isolated because the counselors have such an overwhelming load.”

Garcia said all the delays have made her life harder. She had a full-time job at Ikea, but cut back her hours, hoping the extra time would allow her to power through Pasadena City College.

Over the years, she has shifted her goals from a four-year degree, to a community college associate’s degree, and now to a certificate, which requires fewer credits.

That decision could cost her in the long run.

A study by the U.S. Bureau of Labor showed that in 2009, the median weekly earnings of workers with bachelor’s degrees was about $1,137 — about a third more than workers with an associate’s degree.

Jeffrey MacGillivray attended three community colleges in search of classes and direction.

He started at Los Angeles Harbor College, then tried West Los Angeles College, where he failed to get into any classes, and now he is at El Camino.

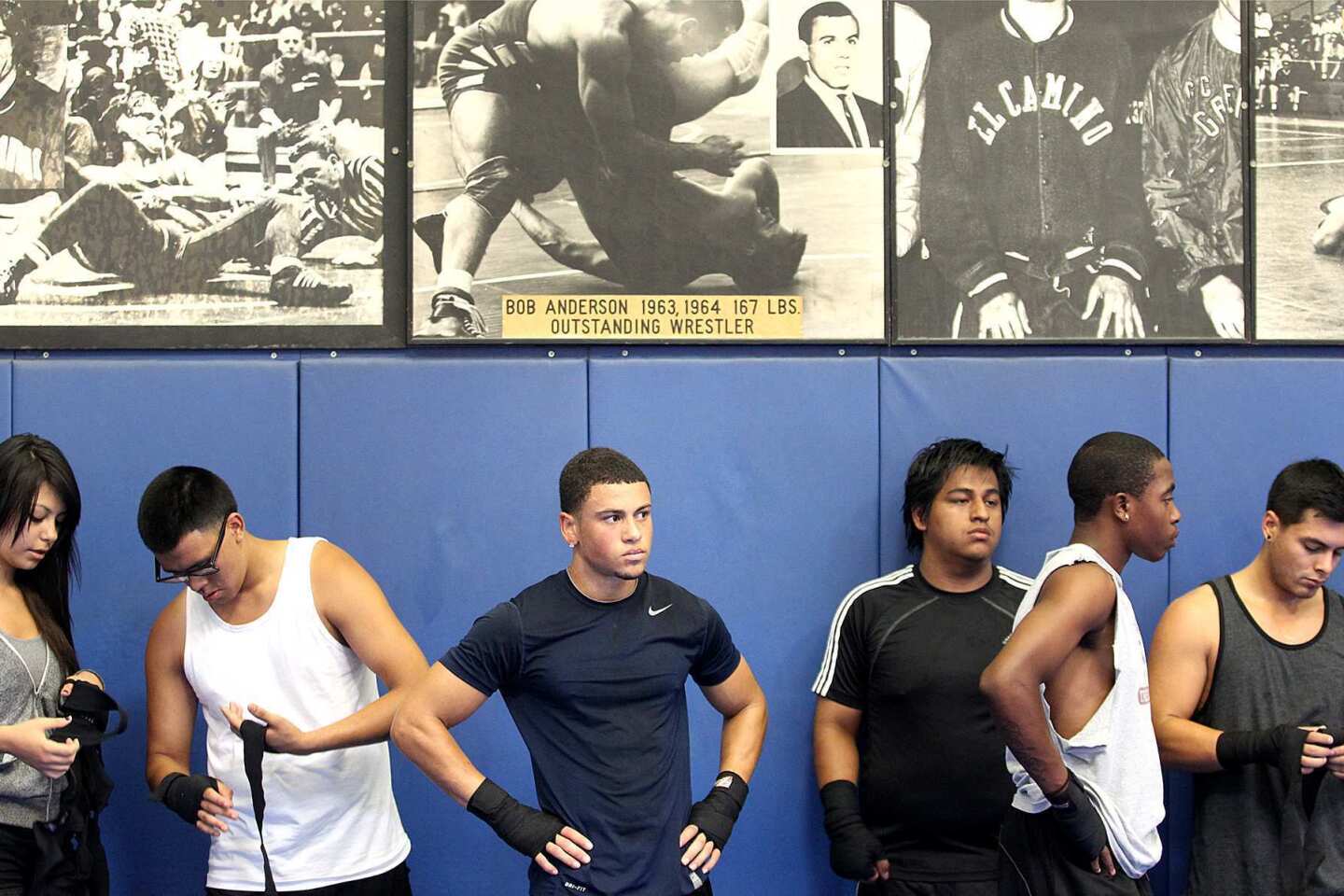

This fall, he managed to find a seat in only one academic class — philosophy. He later added a boxing class to fill some mornings.

“I was thinking I can just go to community college, do my two years and transfer,” said the 20-year-old Redondo Beach resident. “I had no idea I’d probably end up at El Camino for four years.”

MacGillivray has focused much of his attention on trying to play football and run track in community college in hopes of getting a scholarship to a four-year school.

But he has never been able to get enough classes — at least 12 units each semester — to qualify for a team. At El Camino this semester, 98% of class sections are filled to capacity.

“It’s really frustrating, having this goal of running track at a university and graduating with a degree,” he said. “Junior college is being a bigger obstacle than it should be.”

Next semester, MacGillivray may be changing schools again. He was offered a chance to join the Long Beach City College track team — with the possibility that the school could help him get the classes he needs.

For all the trouble, MacGillivray said there is a bright side to his academic wanderings. After two years, he’s figured out what he wants to major in — media arts.

And to his surprise, he has discovered that he actually enjoys philosophy.

On a recent afternoon, he listened intently as his professor lectured on ethical relativism — the belief that morality is linked to the social norms of one’s culture.

“She’s so deep,” MacGillivray said of his professor. “I only got one class, so it’s pretty cool it was that one.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.