Family hopes genome test will help cure girl’s mystery disease

A La Jolla teenager finally gets an explanation for her lifelong mysterious muscle weakness. But will it result in a cure?

- Share via

Honors student Lilly Grossman sat propped up daintily in an armchair in her family's sunny living room, talking about what it was like being homecoming princess of her junior class.

The night of the game — a come-from-behind victory for the La Jolla High School Vikings — she rode around the school's field in a Jeep. At her side was the homecoming prince, a handsome football player in uniform.

Lilly held court the next night in a royal blue dress, her hair twisted into an up-do. When the moment came to dance, she offered her hands to the prince. He looked at her sheepishly, unsure what to do.

"That was awkward," Lilly said with a smile and just the slightest bit of world-weary exasperation.

It isn't easy being 16, social, smart — and sitting in a wheelchair.

Lilly has never been completely "normal" (quotation marks her emphasis).

Afflicted with a mysterious form of muscle weakness since infancy, she has trouble walking, talking and eating. It's hard for her to hold her head up. At any moment, she might fall forward, slumped, until one of her parents lifts her back into position, wedging her into place with an ever-present pillow or two.

Because her speech can be difficult to understand, she depends on text messages and social media to gab with her friends. Sleep eludes her. Seizure-like fits rouse her at night, bringing her parents running to her bedside.

Perhaps worst of all, she spent most of her childhood not really knowing what was wrong with her.

Lilly and her parents wanted answers — even if the journey of discovery would bring both hope and heartbreak.

Lilly, wearing her La Jolla High school colors, zips along the beach at La Jolla Shores with her pet dog. More photos

When scientists first assembled a draft of the human genome in 2000, they hoped sequencing technology could revolutionize medicine by revealing the genetic underpinnings of all sorts of ailments.

Since then, the cost of reading the 3 billion DNA letter pairs that make up a person's genetic blueprint has plummeted from hundreds of millions of dollars to about $1,000. It used to take months; now, technicians can get a read in about a day.

As more people had their DNA analyzed, scientists hoped, it might be possible to find rare mutations that caused poorly understood illnesses. If doctors knew what genes were making people sick, perhaps they could treat illnesses in a more precisely targeted way — maximizing results and avoiding side effects.

Gay and Steve Grossman, sick of hearing doctors grasp at unconvincing explanations for their daughter's woes, thought Lilly would be a perfect candidate for sequencing.

When they heard in 2011 about a study at the nearby Scripps Translational Science Institute that was using sequencing to find genetic causes for mysterious illnesses, they leaped at the chance to take part.

Finding the gene is only the beginning.”— Dr. Jennifer Friedman, San Diego's Rady Children's Hospital

Lilly's neurologist at San Diego's Rady Children's Hospital, Dr. Jennifer Friedman, who has championed the girl's efforts to understand and battle what ails her, signed on to help with the research.

The physician understood the desire to get some answers but also worried about how the process would affect the family.

"I had no idea what we would find," she said. "I was concerned that because Lilly was so involved emotionally, she'd be devastated if we found nothing, or found something bad."

Once Lilly's DNA was sequenced, the researchers found two suspicious mutations, in genes called ADCY5 and DOCK3. Scientists didn't know much about either one.

Reading up in the scientific literature, Friedman saw that a small group of people with mutations in one of the same genes seemed to respond well to a drug called acetazolamide. After talking it over with the Grossmans, Friedman decided to prescribe it for Lilly.

The first night was terrible, but within a week the drug had dramatically improved Lilly's sleep. She no longer woke at night. With better rest, her strength and speech improved. She got more sassy, the Grossmans said.

"I started my new shaking medication a week ago and IT'S ACTUALLY WORKING!!!!!" she wrote on her blog, Lilly Grossman's Life.

She penned a novel, "The Girl They Thought They Never Knew," in which a fictional character named "Lilly" has her genome sequenced, takes a new pill and becomes normal overnight:

Lilly leans back for a few moments during study hall at the La Jolla High library. She has difficulty keeping her head upright for more than a few moments or speaking more than a few breathless words at a time. Her keyboard and smartphone have become her voice, enabling her to compose manuscripts and communicate with teachers and friends. More photos

When I wake up on Friday morning, I feel … different. I can't quite place what feels different. Until I stand up. Straight. Without feeling unstable. I tiptoe into my parents' room. Wait, tiptoe? I usually sound like an elephant running through the house.

In the book, "Lilly" returns to school incognito, starts exacting revenge on kids who've been mean to her, and gets a boyfriend.

But within weeks, the real-life Lilly began having trouble operating her phone, computer and motorized wheelchair — her lifelines to the world.

Friedman dialed back on the new drug, and Lilly's sleeplessness returned.

By last August, on the eve of a long-anticipated trip to visit colleges, Lilly was suffering seizure-like tremors all night. The episodes came every 10 minutes.

"Things aren't as simple as one might assume," Friedman said. "Finding the gene is only the beginning."

Lilly hasn't given up on her dream of being "normal."

Sitting in her living room in December, the only subject that excited her more than homecoming or talking about her book was remembering her trip to UC Berkeley.

Gay offered a few details: A tour guide who also uses a wheelchair squired Lilly around campus, showing her a marble rooftop swimming pool where she might continue her swimming and a specially equipped dorm where she might live with a suite mate.

The university offers unique services to help students like Lilly navigate college on their own and get jobs after graduation. Stores and restaurants in Berkeley are fully wheelchair-accessible — unlike her high school, where she has to rely on her aide to open the library door.

When asked if she might be able to be independent as a university student, Lilly grinned, laughed and pumped a fist in the air.

Everything was about moving on to college now. The previous night, she had stayed out past midnight with "college girls" — friends visiting home on winter break. (She wasn't sharing everything they had to say.)

Lilly enjoys the sunshine on her face at home in La Jolla. More photos

"You're going to have to work hard to get into Berkeley," Gay said.

"Well, I have written a book," Lilly snapped.

She was working on a new novel, in which "Lilly" exacts further revenge on insensitive foes. Soon, she would start writing her admission essays.

Gay, rolling her eyes, said she thought the topic might be "facing adversity."

To function in college, Lilly will have to find a way to sleep better. The family and Friedman are experimenting with her drugs again.

In some ways, it's like starting over.

"We're still trying to figure it out, and I think we will be for a while," Gay said.

The Grossmans have come to terms with the fact that discovering a genetic cause for Lilly's illnesses didn't reveal any obvious way to make her better.

"Sometimes our friends ask, 'What did you get out of this? Things aren't better for Lilly,'" Gay said.

But the Grossmans all say that sequencing Lilly's DNA has been a good experience. Just knowing her gene mutations — and that she doesn't have a condition that could kill her at any time, once a major fear — is "huge for us," Gay said.

And now when they have a sleepless night, the family knows there's someone else out there thinking about Lilly and how to make her better, she added.

"I am so happy that my genome didn't come back all normal and say nothing is wrong," Lilly wrote on her blog soon after getting the results.

This is a marathon — it's not a sprint”— Steve Grossman, Lilly's dad

During the December visit, she said she still felt that way and wanted to get the word out about the promise of genome sequencing. She had been writing about the subject for her school newspaper.

As the day wore on, Lilly's energy seemed to flag and she started to yawn. Steve and Gay helped her move from the armchair to a comfy flowered sofa, where she'd be less likely to slide out of position.

They started talking about the latest hopeful development in the family's genome journey.

As the cost of sequencing was coming down, two more families had learned that their daughters shared the same ADCY5 mutation as Lilly. The mother of one of the girls contacted Gay on Facebook and met with Steve when he traveled to her town on a business trip.

Scripps researchers said they would like to study the three girls as a group, which should improve their understanding of ADCY5 and could point to a treatment.

It could take months for the work to begin. This doesn't bother the Grossmans.

"This is a marathon — it's not a sprint," Steve said.

Listening from her perch on the flowered sofa, his sleepy daughter again lifted a fist, tired but defiant.

Follow Eryn Brown (@LATerynbrown) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

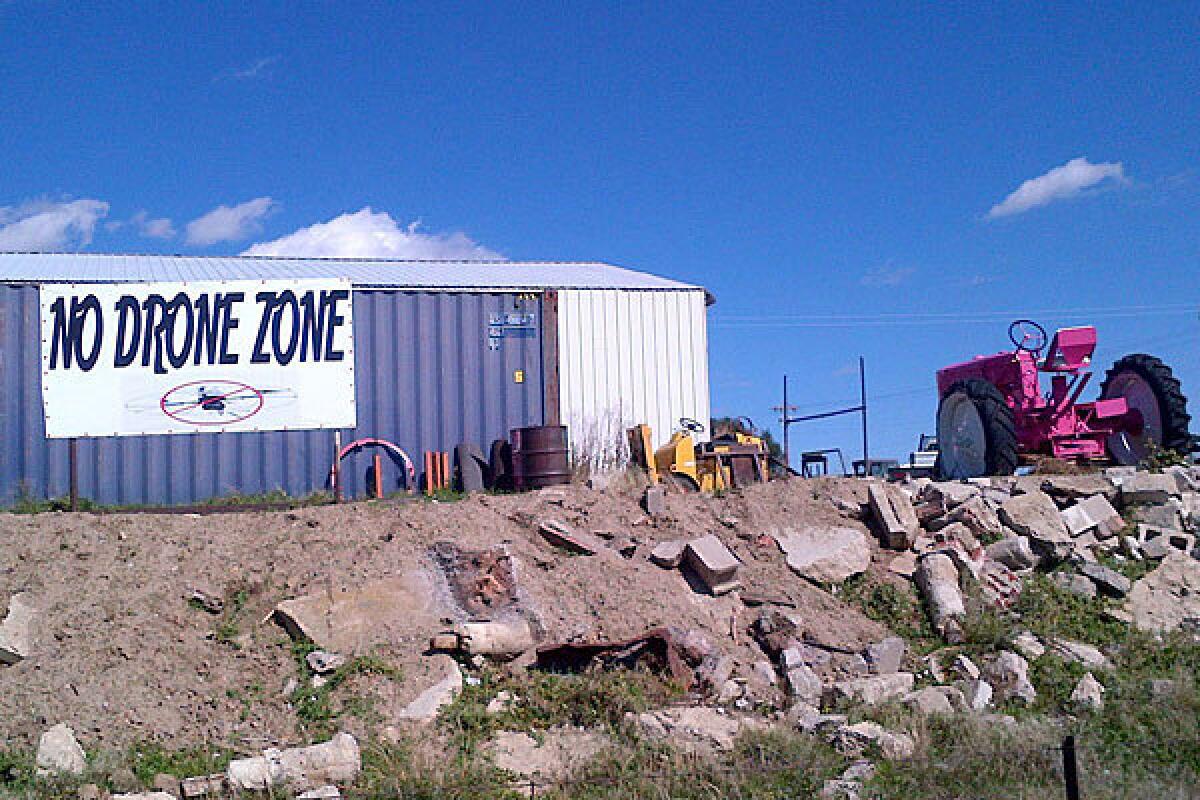

Colorado town declares open season on drones

Which drones are being flown by drug dealers? ... Burglars who want to case neighborhoods?”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.