Man who bombed Los Angeles Aqueduct reveals his story

Mark Berry was 17 in 1976 when he and a friend stole some dynamite and blew apart a gate that regulated the flow of water to the aqueduct.

- Share via

M

ention the name Mark Berry to old-timers at Jake's Saloon in Lone Pine and you get winks and knowing smiles.

His treacherous exploit has been whispered around the Owens Valley for nearly four decades, though Berry never talked much about it with anyone.

On a warm autumn afternoon recently, Berry settled into a lawn chair under a massive shade tree behind his home in the eastern Sierra. He took a deep breath and told a story few know the truth about.

"It wasn't a planned deal," said Berry, now 54. "I was an impressionable kid at the time, just 17."

Berry and his friend, Robert Howe, were caught up in the anger that then hung over the Owens Valley. The environmental damage caused by the Los Angeles Aqueduct, built in the early 1900s to divert much of the water from the region to the growing metropolis 200 miles away, was worsening and Owens Valley residents were exasperated.

"Things got out of hand," Berry recalled.

The friends stole two cases of dynamite and headed to the aqueduct.

The night of Sept. 14, 1976, Berry and Howe, 20, were waiting for their girlfriends to get off work at an ice cream parlor.

To kill time, they bought a six-pack and drove to a secluded spot along the Owens River. The two walked along a bone-dry river channel where water should have been flowing.

"Robert got real mad about that," Berry recalled. "He yelled, 'I can't believe this. They're not letting any water out. I'm going to fix this once and for all.' "

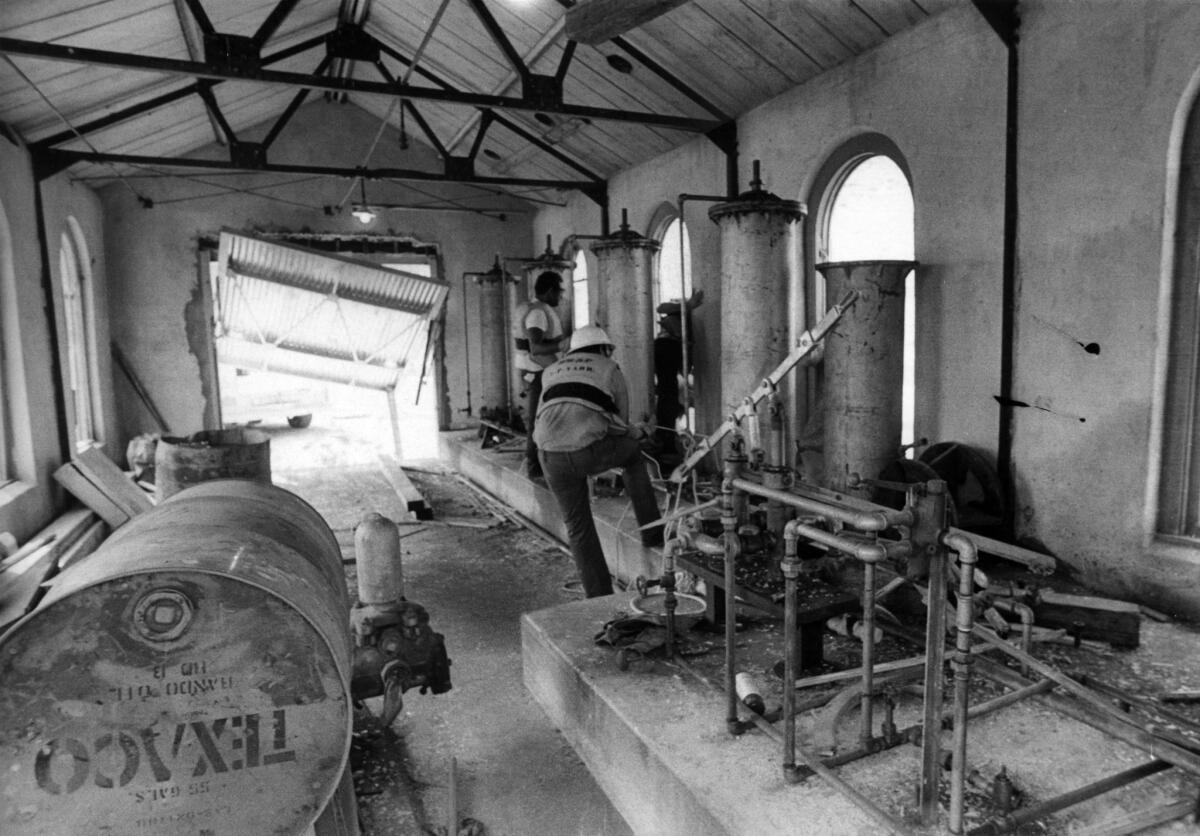

The interior of the Los Angeles Aqueduct's Alabama Hills gatehouse after an explosion buckled the floor and blew out the windows and door. This photo was published in the Los Angeles Times on Sept. 16, 1976. (Ben Olender) More photos

In Howe's root-beer-brown Ford Pinto, the friends drove to a hut on the western outskirts of town where Inyo County stored dynamite used to build trails and dislodge boulders and logs.

In recollections supported by court documents, Berry said Howe used a crowbar to break the hut's locks. They grabbed two cases of dynamite, blasting caps and about 20 feet of fuse.

Howe drove back to his house, where he stuffed the end of a 5-foot-long piece of fuse into a blasting cap and crimped it with a pair of pliers. Then he unraveled one end of a stick of dynamite, pressed the blasting cap into it and put it back in the wooden case. Berry gouged a hole in the lid and pulled the fuse through.

They drove back to the aqueduct and resumed drinking. Shortly after midnight, they lugged the rigged case of dynamite about 30 yards up a hill to the gatehouse. Howe shoved it up against the middle of five gates, lit the fuse and started running.

A few minutes later they parked by the side of the road, and listened. Nothing.

They drove closer to the gates and stopped. "Bang. We heard the explosion."

The blast ripped apart a 4-foot-wide steel gate that regulates the flow of water to the aqueduct. Windows were blown out of the gatehouse atop the spill gates and its concrete floor buckled.

We’d all thought about doing something like that—but they actually hauled off and did it."— An Owens Valley resident

About 100 million gallons of water meant for Los Angeles were instead flushed into Owens Lake, which had been dry since the Department of Water and Power opened the aqueduct in 1913.

On the way back to town, they dumped the second case of dynamite into shrubs. A minute later, a tire blew out. Berry changed it as Howe kept an eye out for law enforcement officers.

Word of the explosion spread instantly.

Inyo County Sheriff's Det. Jim Bilyeu arrived at the scene to find a crowd applauding the smoldering damage. The air was filled with the banana-like smell of nitroglycerin.

"Initially, we thought it was done by the Weather Underground terrorist group because we had intelligence indicating they were planning to attack transmission towers in our area," Bilyeu said. "But it didn't take long to figure out the culprits were amateurs."

Al Carrasco at Jake's Saloon in Lone Pine, Calif., recalled hearing the news of the Los Angeles Aqueduct bombing. "I rolled my eyes and joshed, 'It was probably one of my relatives up there,' " Carrasco said. "It turned out to be true. Mark Berry is my cousin." (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times) More photos

At Jake's Saloon recently, Al Carrasco recalled hearing the news.

He was working for the DWP in downtown Los Angeles at the time when a man ran into the vehicle shop, waving his arms and yelling that someone had bombed the aqueduct.

"I rolled my eyes and joshed, 'It was probably one of my relatives up there,' " Carrasco added.

"It turned out to be true. Mark Berry is my cousin."

In the weeks after the blast, Howe, the son of an Inyo County probation officer, and Berry, the son of a maintenance worker at a Lone Pine school, became underground celebrities.

"We'd all thought about doing something like that — but they actually hauled off and did it," recalled a woman gas station store clerk who asked not to be identified because she feared losing her job. "So we gave them rousing shoulder punches and clinked beer bottles in their honor."

Berry said his father, as yet unaware that his son was one of the culprits, boasted to a neighbor, "If I ever find out who bombed the gates I'll buy him a steak dinner."

The FBI, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and the Inyo County Sheriff's Department built a case against Berry and Howe based on physical evidence and information provided by confidential informants, including a friend of Howe's at the time who now owns a construction company nearby.

Howe and Berry were indicted in January 1977.

Howe was sentenced to 90 days in Inyo County jail and three years probation. After that, he left town and hasn't been heard from since.

Berry was sentenced to 30 days in juvenile detention. His records were sealed. The court ordered Berry to enroll in a nearby community college, where he studied rocket and aviation engineering.

"That sentence was the best thing that ever happened to me," Berry said. "I went on to work at airfields in states including Montana and Alaska."

Berry returned to Lone Pine in 2000. By then, 24 years had passed and his exploits had faded among the locals, so much so that Berry landed a good job in Owens Valley.

He works for the DWP.

His job? To make sure the aqueduct is safe and is properly diverting water to the metropolitan region to the south.

Berry says he regrets his actions of 37 years ago.

"There was a time when the DWP did whatever it wanted to around here," he says. "But times have changed, and so have I. The DWP has done heroic work on behalf of the Owens Valley."

He credited the DWP for preventing development that would have turned the wide open rugged land into a distant suburb of Los Angeles.

DWP officials in Los Angeles were unaware that one of their workers had bombed the aqueduct until told by The Times.

An aerial view of the Alabama Gates along the Los Angeles Aqueduct. A 1976 explosion ripped apart the steel gate, which regulates the flow of water to the aqueduct. About 100 million gallons of water meant for Los Angeles were instead flushed into Owens Lake. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times) More photos

After considering the situation for several days, Jim Yannotta, manager of the aqueduct, issued a statement, saying Berry's juvenile record has since been expunged and the city would have had no way of knowing about his involvement.

"It's clear that this was a wrongheaded act of vandalism … by a youth who had been drinking and that he and his accomplice were rightly held accountable by the law," Yannotta said.

The bombing was "a reflection of a period of much more tense relations between people in the Owens Valley and L.A.," he said. "We are grateful that relations have improved."

As Berry wrapped up his tale, the conversation turned to a loose end.

The day after the bombing, someone strapped a stick of dynamite to an arrow and shot it at a memorial fountain for William Mulholland, the aqueduct's chief engineer, in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles.

The dynamite didn't explode.

"I have no idea who fired it," Berry said with a smile. "It wasn't me."

The sun fell low. Berry left his lawn chair and headed to a cliff on the outskirts of town. As he gazed at a tableau of spring-fed streams, spiky lava fields and outcroppings and granite walls, he said: "This is the most beautiful place I know on Earth."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.