A glorious flock

- Share via

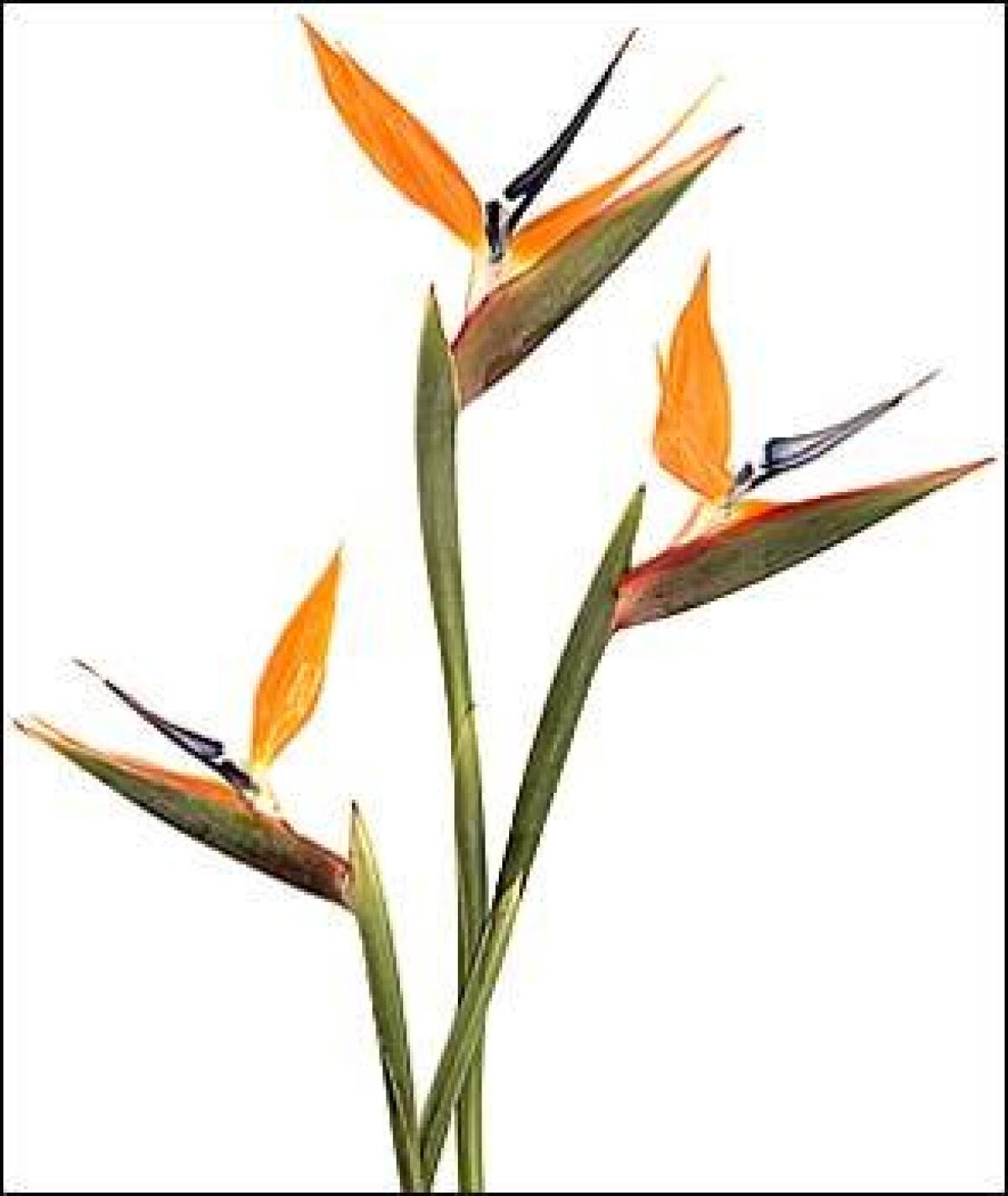

There is a kooky poignancy to the city flower of Los Angeles. No other plant comes quite so close as the bird of paradise to having the actual aspect of an animal. It’s like a bird, yes — a crane — yet what’s so moving is its quality of high-chinned hesitancy, as if it’s lost but is too shy to ask for directions.

It’s all the more touching to learn that the bird of paradise is lost. Stranded in traffic islands outside LAX, the convention center and every other courtyard apartment complex in Los Angeles, it is thousands upon thousands of miles from its home in KwaZulu-Natal. More than two centuries ago, it was bagged from its perches in the Eastern Cape and Natal province of South Africa and whisked off into the plant trade by an English explorer. From that moment onward, the plant known as ikhamanga in Xhosa and inkamanga in Zulu became captive to our imaginations. In the last two centuries, we have renamed it bird of paradise, idolized it and reviled it, made it the flower of royals, the emblem of star-crossed love, the Los Angeles city flower and finally, the floral retort to Florida’s plastic pink flamingos. The only thing we have failed to do is consider the plant on its own merits.

The first ones to arrive in Europe were recorded in 1773 at the Royal Gardens at Kew, near London, where they made such an impression that the species was named Strelitzia reginae (pronounced struh-leet-ZEE-uh), after the duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. This was no small honor. The duchess, Charlotte, was also the queen of England, wife of George III. A certain Col. Warren of Sacramento introduced them into California in 1853, and “Southern California Gardens: An Illustrated History” by Victoria Padilla finds Strelitzias wowing the good burghers of Santa Barbara in the Montecito nursery of Joseph Sexton in the 1870s.

In 1932, they went from status symbol to sex symbol. David O. Selznick bought the rights to a Broadway play, hired King Vidor to direct, Dolores Del Rio and Joel McCrea to star, and selected Waikiki as location. “I don’t care what you use,” Selznick told Vidor regarding the film, “so long as we call it ‘Bird of Paradise’ and Del Rio jumps into a volcano at the finish.”

By World War II, Japanese flower farmers in Southern California were cultivating them by the acre. Though much of the lucrative farming for the florist trade was seized during internment, Japanese affection for the bird of paradise held. It remains in the cutting repertoire of origami.

But such delicate regard was not L.A.’s style. In 1952, Manfred Meyberg, president of Germain’s Seed and Plant Co. and the civic booster behind the “Los Angeles Beautiful” campaign, succeeded in having it made the city flower. This time it was a religious association — only the bird of paradise seemed good enough for the City of Angels — but in the end it might have been kinder to throw it in a volcano: regal, sexy, tragic, imprisoned and now divine Strelitzia became standard-issue stuffing for civic beds.

Which brings us to the current state of affairs. The bird of paradise is no less spectacular today than it was 200 years ago: Queen Charlotte would recognize the specimen growing outside the Burbank IKEA as her namesake. However, as poor old Strelitzia gained in popularity, its snob appeal plummeted.

There are few crueler fates for an exotic plant than to lose curiosity value. The Huntington Botanical Gardens used to have lots of them, says Kathy Musial, curator of living collections. As they became about as chic as garden gnomes, the Huntington has slowly been taking out stands dating back to Henry Huntington’s time.

Speaking from his cellphone in the Department of Agriculture Plant Inspection Center at LAX, where he was checking a new haul of Thai euphorbias and aspidistras through customs, L.A. nurseryman Gary Hammer says that he no longer handles bird of paradise. It’s a “Home Depot plant,” he says.

The Huntington and Hammer are in the exotica business. The variety most likely to be spared at the Huntington is the rarer, sword-leaved juncea variety, Musial says. On the rare occasion that Hammer stocks Strelitzias, he will only have truck with juncea too, Hammer says. But before the rest of us start ripping out good old reginae, he warns, we should remember why it is so popular. The doughty grace of this African import has proved perfect for Los Angeles.

According to the textbooks, it shouldn’t be, Musial says. Strelitzias are from the Eastern Cape of South Africa, and our Mediterranean climate is more like that of the Western Cape, which receives no summer rainfall. It may be our clay and largely alkaline soil, she speculates. Whatever it is, Musial agrees with Hammer: Something about the Strelitzias equip them to cope with Southern California uniquely well.

It’s the fleshy roots, says Ernesto Sandoval, curator of the Botanical Conservatory at UC Davis. The Strelitzia genus is part of an order of plants that also takes in bananas, heliconias and traveler’s palms. They can live as long as trees, get as big as trees, but are in fact big herbs, with rhizomatous roots, like mint or milkweed, but fleshier. Once a plant is established, these roots, Sandoval says, can store surprising quantities of water, then mete it out slowly. This ability combined with water-efficient waxy foliage and the ability to suspend growth during drought has allowed the plant to adapt to Los Angeles as artfully as a native.

Hammer has only one warning about planting too close to the house: They get bigger. Give bird of paradise enough water, sun and fertilizer and the 10-inch tall plant in the one-gallon pot is capable of turning into a 6-foot-high plant. Mistake a S. reginae for the Strelitzia nicolai, a tree version, and it can be 30 feet. So don’t put it under a window unless you want to block the view.

Wherever you put it, be sure you like it. The roots establish themselves so firmly that they are a job to remove, but they aren’t foundation busters, Sandoval says. In fact, they are a good choice to plant near buildings or by concrete walkways because they don’t thicken like tree roots.

The most important thing when placing them is not to put them anywhere you wouldn’t put a hummingbird. Strelitzias won us over because of the way they look — their gracious architecture, the stunning blue petals and orange sepals — and that they flower nearly year-round. Too often gardeners and urban planners forget that flowers have pollinators. Strelitzias are veritable nectar fountains. Placing the plants in the line of traffic is the equivalent of putting an ice-cream truck in the middle of a freeway.

A single Strelitzia popping out from a hedge or run of aloe can be as charming and comical as coming upon a Miró sculpture. Yet there is that haunting quality, that quirky vulnerability. Plant them en masse and the effect changes. They somehow become awe-inspiring. We see the flower that is now a badge of pride in new South Africa, on the new coat of arms for KwaZulu-Natal, and the emblem of the country’s highest honor in sport and art, Order of the Ikhamanga. We see them as what they are: a glorious flock of birds from somewhere else. Somewhere special.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Choosing the right species for your space

If you want a commotion in the flock, bring up the subject of how many species there are of bird of paradise. In 1811, the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew claimed six. The number has been falling ever since, as botanists came to appreciate the variability possible in one species, Strelitzia reginae.

Strelitzias can be divided from root, creating armies of clones, but the plants take so long to recover that nurseries opt for seedlings. These can be unpredictable as any group of offspring, so S. reginae can have almost blade-like leaves or the paddle-shaped ones we know.

The flower colors can include orange, blue, gold and white. Heights can be as variable as a seventh-grade basketball team.

Of the truly different varieties, with dramatically different habits, you won’t find S. alba or S. caudata in the trade here. For white flowers, look for the tree, S. nicolai. Just keep in mind that sweet little “flower” on the seat next to you will turn into a 30-foot-tall tree.

*

Strelitzia reginae

The classic bird of paradise bush, a waxy-leafed “herb” from the Eastern Cape province and KwaZulu-Natal. Typical clumping habit, from 4 to 6 feet tall. It’s capable of withstanding a low 28 degrees. As long as the soil doesn’t freeze, frost-damaged foliage will return in spring.

Plant tags will always stipulate pampering: first-class drainage, full sun, monthly fertilizer, regular water. Once the seedling is established, it can grow in Southern California with predominant shade, no fertilizer and the occasional slow watering and light shower with the hose.

For want of the plant’s South African pollinator, the sun bird, which carries the pollen on its feet, seeds will not form without hand-pollination. When you buy seeds, note the little hairy tuft, what UC Davis botanical curator Ernesto Sandoval calls “a little toupee.” Sandoval thinks it is to attract ants to scarify the shell, eating it so that the seed can germinate. Propagators have to stand in for the ants. Martin Grantham, greenhouse manager at San Francisco State University, recommends soaking the seeds in an ethephon solution, a chemical used to ripen tree fruit.

Or you could buy a seedling at Home Depot. The one-gallon purchased there, at Armstrong or any leading nursery, will represent three years of tender loving care.

*

Strelitzia reginae, var. juncea

A bird of paradise that still impresses novelty junkies. The leaves are blade-like, and the plant is altogether longer, skinnier, grassier-looking than S. reginae. Sandoval recommends planting red yucca, agave and succulents for a southwestern hummingbird garden.

*

Strelitzia reginae, ‘Mandela’s Gold’

Same care as S. reginae, but with a gold flower bred at South Africa’s Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden.

*

Strelitzia nicolai

Nicknamed the “desert banana” in South Africa and white bird of paradise in garden centers, this is a tree with 4-foot-long, banana-like leaves and white flowers. Capable of growing to 30 feet tall. Treat as one would a banana tree: moderate sunshine, occasional deep water, plenty of room.

Emily Green can be reached at [email protected].

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.