Great Read: The 7-foot Chinese tourist boxing in Oscar de la Hoya’s world

Taishan Dong moves away from opponent Tommy Washington as referee Jack Reiss delivers a ten-count in a heavyweight bout at Fantasy Springs Resort in Indio.

- Share via

The new Chinese-language sign had been up for only a few weeks outside George Gallegos’ personal injury law office in Monterey Park when a 7-foot-tall tourist from Beijing walked through the door.

Taishan Dong was on his honeymoon, and he wanted information about green cards for him and his new wife. But Gallegos couldn’t help but be distracted.

Dong was fresh from a workout at the L.A. Fitness next door. With rippling muscles and a jaw that jutted like Dolph Lundgren’s, he looked, Gallegos recalled, “like a superhero.”

Gallegos dutifully answered Dong’s questions for a few minutes, but his mind churned with possibilities. The attorney had grown up on the fringes of East L.A.’s boxing world, and for years, he’d wanted to break into the business.

The conversation quickly turned to fighting. Dong mentioned he had kickboxed in Japan, and for the next two hours, they crouched behind Gallegos’ computer and watched Dong knock out a former NFL lineman on Chinese YouTube.

Gallegos looked up at Dong.

“Did you ever think about boxing?”

::

Many Monterey Park attorneys have Chinese signs and Mandarin-speaking staff. But Gallegos, 43, may be the only one who grew up boxing in a Boyle Heights gym. He had subscribed to KO Magazine as a kid and idolized fighters such as Julio Cesar Chavez and Paul Gonzales, but he knew he’d never be a boxer.

As a lawyer, Gallegos offered his services to boxers embroiled in contractual disputes and refereed amateur mixed martial arts fights in his spare time. He tried to break into the industry once in 2009, promoting a local MMA fight. He lost $30,000 when some of the fighters dropped out.

Then Dong walked into his office in December 2013.

“To me, this was bigger than the chance of a lifetime,” Gallegos said. “How often do you find a Chinese guy that’s 7 feet tall, cut like him and interested in boxing?”

Dong grew up in the Gansu province of China, and by the time he was 14, he was 6 feet tall and everyone in his rural community told him to play basketball.

He joined a team, but quit after six months. He wanted to make a living with his fists instead.

“I just like to fight,” said Dong, 27, who doesn’t talk much about his past, and ignores most personal questions, even posed in his native language, Mandarin.

He kickboxed and learned the combat sport Muay Thai. He gave himself a nickname and a compelling origin story. Born Dong Jian Jun, he named himself Taishan after climbing the mountain of the same name. He told reporters he wanted to be the Yao Ming of kickboxing.

But now he had discovered a more ordinary ambition: Like millions of Chinese immigrants before them, he and his wife decided that they wanted to move to Los Angeles to raise their baby daughter.

“Fighting can bring me and my family a better life,” he said.

And to get that, he needed Gallegos — at least, for the moment.

The lawyer had been burned before by the boxing world. But maybe this time, the stars were aligned.

::

Dong had never boxed, but he had the kind of physique that sparks dreams of multimillion-dollar fight cards and huge Chinese endorsement deals. Just days after Gallegos emailed Dong’s YouTube videos to Top Rank and Golden Boy, the nation’s two largest boxing promoters, the phone began to ring.

Golden Boy Matchmaker Robert Diaz remembers that he had just one question after he saw Dong’s videos. “I asked them, ‘How soon can he come over?’” he said.

Dong signed a five-year promotional contract with Golden Boy that ensured that all his fights would be televised — an unheard-of deal for a fighter without a single boxing match under his belt.

To me, this was bigger than the chance of a lifetime ... How often do you find a Chinese guy that’s 7 feet tall, cut like him and interested in boxing?

— George Gallegos

A few weeks later, Dong was in the gym with a new career, an apartment in Glendale and a brand-new athlete’s visa.

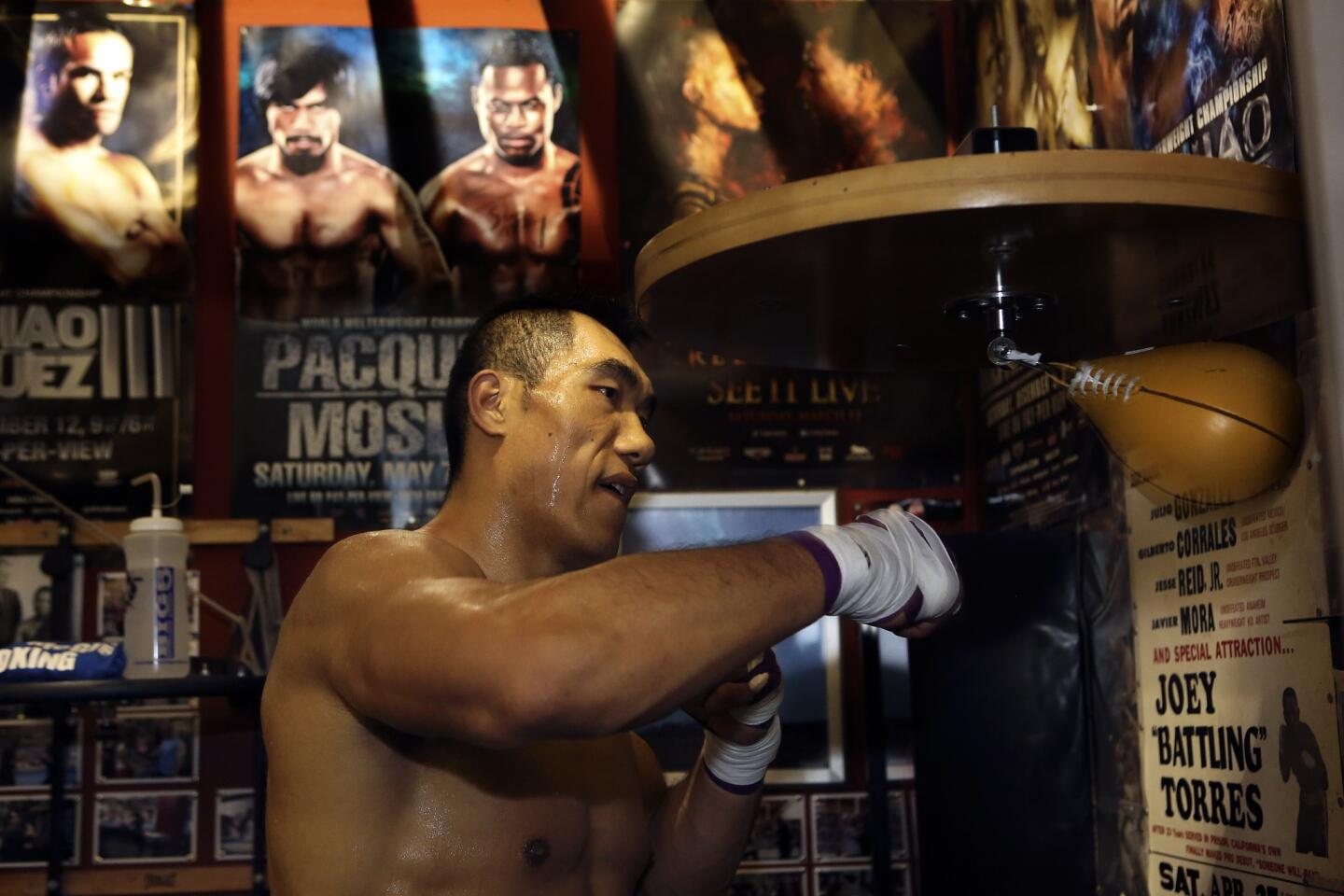

In the ring, his speed needed work, but his power was stunning. His training sessions sounded more like the operation of heavy machinery than boxing, thunderclap blows punctuated by breaths hissed through clenched teeth like pressurized steam.

“Let me tell you, that man can punch,” said John Bray, the trainer Gallegos hired to make Dong a boxer. “I was feeling it every day. My shoulders, my back, my neck. He hits harder than anyone I’ve ever trained.”

A crowd of boxers, trainers and gym rats always gathered ringside when Dong trained at the Burbank Fight Club, and Gallegos collected their compliments and admiring statements like a proud father. He loved to tell everyone that a trainer had told him Dong punched harder than Mike Tyson.

What began as a partnership between Gallegos and Dong became a friendship carried out in pantomime, mock punches on the arm and a mixture of broken Chinese and English.

Gallegos introduced Dong to Thanksgiving, setting up a spread of turkey, stuffing, mashed potatoes and rolls, eaten off paper plates in the rec room of Dong’s apartment complex. They went out for lobster in Alhambra on Chinese New Year and shopping for Abercrombie and Fitch clothing, Dong’s favorite. Dong loved hamburgers and ate six In-N-Out burgers at every sitting, until Gallegos taught him about double-doubles.

Gallegos downsized his practice and let go of an attorney, taking on her work to free up money to finance Dong’s career. He assumed a dizzying array of new responsibilities in boxing: chauffeur, interpreter, fight manager, concierge. He found Dong an apartment and helped pay for it, and gave him a bed, a desk and a table from his own house.

“I’m not really a dreamer,” Gallegos said. “But I started to think that this could actually work.”

The first few minutes of Dong’s professional boxing career, at San Francisco’s Longshoremen’s Hall, were promising. Footage from the fight showed him dropping his opponent with a piston-like blow to the head after two rounds.

Dong clambered atop the ropes and raised his fist, clumsy with elation. Next to him, Gallegos’ face was stoic beneath a salt and pepper pompadour, but he was standing somewhere he had wanted to be since he was a kid: inside the ring.

::

At the Fantasy Springs Special Events Center in Indio, a fight night soundtrack of mariachi and hip-hop gave way to the pop sounds of Andy Lau’s “Chinese People.”

Dong stepped out from behind a curtain and raised his gloves, swaggering toward the ring for his second match.

The announcer introduced him as an “undefeated heavyweight sensation” from Beijing, and at 1-0, it was technically true.

The fight ended with an unconvincing knockout, and the crowd roared.

Boxing, a sport hungry for spectacle, had discovered an intriguing new character. YouTube was flooded with grainy reproductions of Dong’s first fight and training sessions. Before the fight, Oscar De La Hoya had uploaded a photo of Dong to his personal Instagram account that was liked 1,800 times.

Dong began to see himself on the front page of local newspapers; plastered across a billboard, an intense glare leveled at the 60 Freeway; leading the home page of ESPN.com under the headline “Chinese Boxer Taishan Dong is 7 feet tall and here to conquer the world.”

The attention went to his head, Gallegos said. After his first fight, Dong asked Gallegos if he could fight Mike Tyson.

Dong’s compensation couldn’t keep pace with his viral stardom. He was a 2-0 boxer with a Wikipedia page, but most of his fights were in an Indio casino where his food came from meal coupons at the hotel buffet. The purses from his deal with Golden Boy began to feel small.

Pretty soon, all of Dong and Gallegos’ conversations were about money.

::

Before Dong’s third fight, in March, Dong’s new trainer, Buddy McGirt, took him through his paces in the dressing room. For the last few months, he had trained Dong using a three-word vocabulary: “Quick,” “boom” and “good.”

Dong’s fists smacking against McGirt’s pads were the loudest sounds in the room. Weeks before, Dong and his wife, Chelimuge, had complained that it was too noisy in the locker room before fights, so Gallegos stayed mostly silent.

As the announcer introduced the first fight, Gallegos presented Dong with a shimmering golden robe inlaid with ornate red trim. Dong held it up against his body in the mirror, laughed and put it on. He threw a playful punch in Gallegos’ direction.

But the robe was another source of tension. Gallegos had ordered the robe after showing it to Dong, but Chelimuge thought it was a waste of money. After she saw it, she asked Gallegos to stop speaking with Dong without her present.

SIGN UP for the free Great Reads newsletter >>

Barely a word was spoken until the start of Dong’s fight, which went three rounds and ended in a decision. Dong struggled to subdue Roy McCrary, a much older and shorter fighter. Boxing critics began to raise questions about Dong’s ability.

But Dong didn’t need to box well to get attention. Weeks after the fight, Gallegos’ phone rang with an offer to produce a documentary about Dong. The filmmaker wanted to meet, but Dong wasn’t happy with the terms and the project fizzled. Ever since he was a 6-foot-tall 14-year-old, people had been asking him to sign pieces of paper that would dictate his future, and he had grown suspicious of any kind of contract, Gallegos said.

Dong and Chelimuge, who declined interview requests in recent weeks, were especially unhappy with Gallegos’ manager contract. They held formal meetings with him in which they unspooled a long list of complaints: Gallegos didn’t bring in enough money. He didn’t smile at the dinner table after the fight, and failed to offer timely congratulations.

Gallegos tried to suggest that Dong’s wife, a tennis instructor, was playing too much of a role in Dong’s training. But Dong trusted Chelimuge more than anyone.

“My wife is the reason I’m here,” Dong replied.

::

By Dong’s fifth fight, in May, Gallegos couldn’t even get a ticket for the match. He reached out to Golden Boy to get seats, but he and his fiancee ended up closer to the ring than Chelimuge, and she was deeply offended.

In July, Gallegos got a letter from the California Athletic Commission informing him that Dong had requested an arbitration hearing, a precursor to terminating their relationship.

Dong’s letter in support of the arbitration claims there was mistrust and suspicion from the beginning. Gallegos made him sign contracts he didn’t want to, Dong alleges. The payments for each fight kept getting lower, and Gallegos wouldn’t meet with Golden Boy to address the issue. Gallegos wouldn’t provide him with Mandarin translations of documents before he signed them, Dong’s letter says.

“Gallegos wanted me to take his word for it, claiming I would be unable to comprehend what was written,” the letter says.

Gallegos disputes Dong’s claims, saying his office spent hours translating headlines, documents and forms.

At a restaurant a block from where he met Dong, he struggled to explain what happened to the relationship. He said he had yet to see any profit from Dong’s boxing career, despite what he called a nearly six-figure investment.

He took out his phone and scrolled through photos from the last year. Only his dog was pictured more than Dong.

“It was a dream, the way everything lined up at the beginning,” Gallegos said. “But it just didn’t turn out the right way.”

These days, Gallegos has found another fighter to represent, a 6-foot-7 boxer with several amateur fights under his belt named Paulius Ritter.

Ritter lost his first fight in August, but if he gets a few wins, Gallegos could find himself in the ring again, with a familiar face across the mat:

“He’ll probably be matched up against Taishan.”

MORE GREAT READS:

Jesse is a typical boy in probation-run foster care: unwanted

A failed bronco gets a shot at rodeo redemption

In India, a legend keeps a town nearly door-free

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.