Great Read: To survive in the U.S., Chinese bookstores evolve way beyond books

- Share via

At World Books on Atlantic Boulevard, Lily Li picks up the phone to transact one of her first sales of the day.

“Hello, this is World Books,” says Li, 60. “Can you add $60 to this phone card?”

She hands the card back to the man waiting at the counter, then picks up the phone again to make her next sale: a small commission fee for helping a customer buy an ad in a Chinese newspaper.

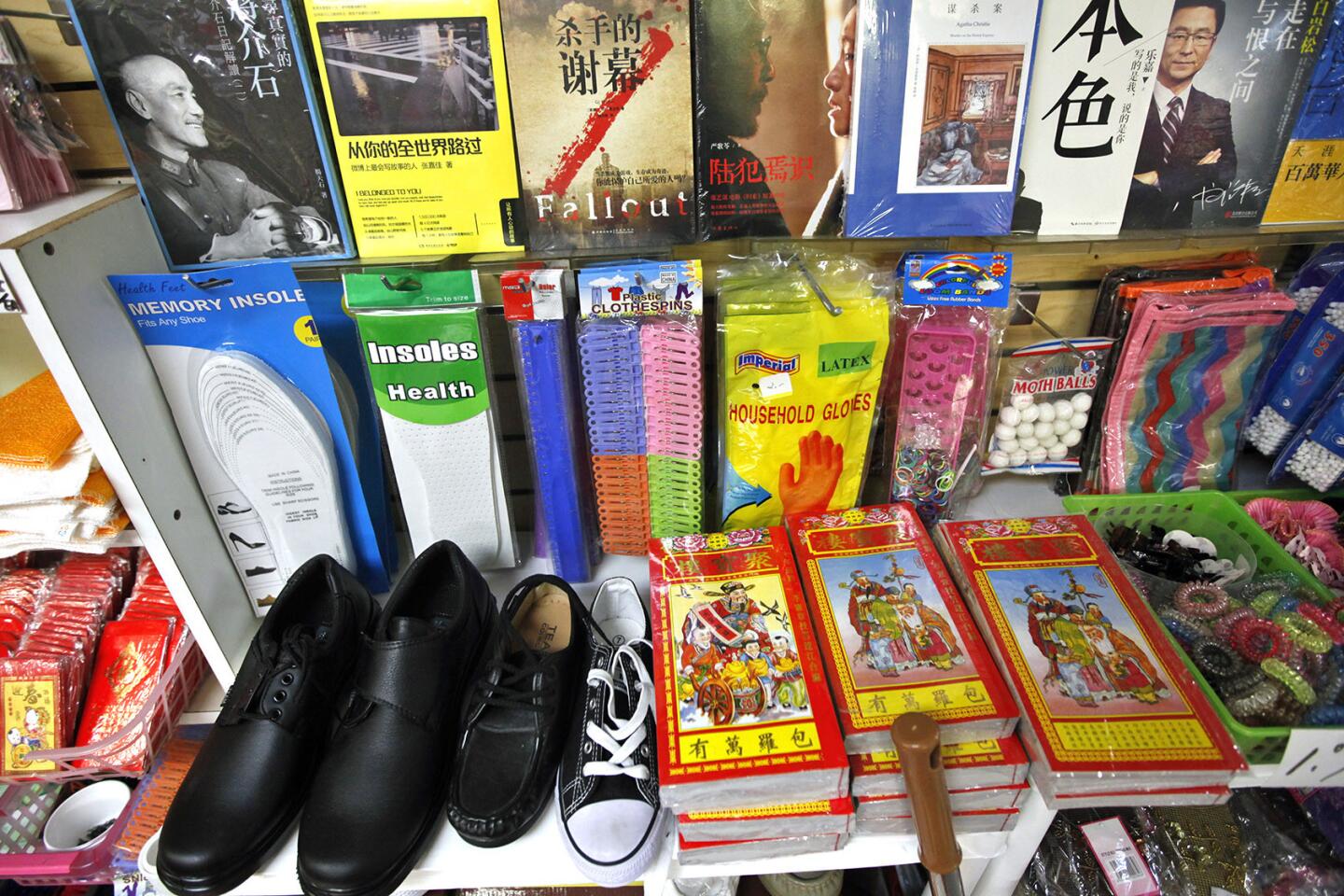

On her shelves, baby turtles swim in bright plastic tanks next to four cans of Sprite, two cans of Lipton Brisk iced tea and a pamphlet advertising Scientology. Walking sticks hang off a cart of adult DVDs. Shampoos and back scratchers tempt from a display by the door.

As for books, they mostly gather dust.

Internet competition has forced bookstores across the nation to close, but in the San Gabriel Valley, they’ve evolved. Chinese bookstores ship packages, repair laptops, supply lottery tickets. One bookstore became a classroom, another a convenience store.

Their owners came to America with the same dream, only to watch it fade. To keep it alive, they’ve cut corners from it, painted it a different color, repackaged it.

“A bookstore, you can do anything with it,” says Helen Duong, who teaches English and Chinese, hosts calligraphy and art lessons and offers free classes on how to pass the citizenship test in a classroom space she created in the back of her Alhambra bookstore.

“It doesn’t matter what it is,” she says, “as long as it’s something people need.”

::

Rebecca Zhang waves a smudged pink spiral notebook in disgust. It records sales at her shop, and today, it’s blank.

“If you want to sell books these days, you’re doomed,” says Zhang, who owns another World Books, this one on Garvey Avenue in Monterey Park.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Nov. 25, 12:47 a.m.: An earlier version of this article said that Rebecca Zhang owns a World Books store on Garvey Boulevard. The street is Garvey Avenue, in Monterey Park.

------------

So she sells whatever she can get her hands on — plaid sandals, luggage, phone cards, mops with specialized buckets to spin them dry. She just received a shipment of feng-shui calendars for next year, ordered early to beat the competition.

Her bookstore is one of several storefronts crammed inside the Hong Kong Supermarket, a pastel-pink grocery store that is starting to show its age.

When the supermarket’s automatic doors jerk open, a heavy odor rushes out, part baking bread and raw fish, part rotting vegetables and cleaning solution, like pungent breath poorly masked. All around the supermarket, there are cracked, water-damaged tiles and grime outlines left by floor displays come and gone. In each department, a photocopied sign repeats a typo a dozen times: “Simile! You’re on camera.”

Zhang’s bookstore is at the end of a row of small shops that line the front wall of the grocery store. She doesn’t notice the smell anymore, but other things are harder to ignore — like the seafood display about 20 feet from her counter.

“This place used to be so clean,” she says.

Zhang never wanted to sell books. In Beijing, she was a nurse, and when she first came to America, she helped care for the children of birth tourists — pregnant mothers who fly to America to give birth to children with U.S. citizenship. She bought the store about 10 years ago because a friend gave her a good price.

Back then, there was so much foot traffic that two cashiers ringing up sales simultaneously couldn’t keep lines from forming.

She shakes her head as she thinks about the last decade — book sales declining, her store space cut in half.

A few years ago she tried to sell the lease to someone else, but no one wanted it. She sold phone cards for a while, but then the Internet stole that business too. Today, she’s pushing mah-jongg. She overhears two shoppers mention the mah-jongg sets in the window and rushes out to invite them in.

“We’ve got that in here,” she says. “Do you want big ones or small ones?”

The shoppers finger some plastic sandals and ask about the price, which Zhang offers eagerly — $5. But they are only looking, and they leave after a few minutes.

::

At NHK Books in Alhambra, a man in a pinstripe shirt and a baseball cap and a cook in a smudged apron approach Cecilia Ng at the register.

The cook buys a soda and some chips and leaves. The man buys a lottery ticket — his fifth or sixth of the night. Neither customer notices the books on display at the back of the store — mostly comic books for kids.

“We used to sell books,” Ng says. “Now we’re more like 7-Eleven for Chinese people.”

The bookstore turned convenience store is part of a big chain of Chinese bookstores originating in Hong Kong that dates to 1954. The store even publishes a manga based on the bookstore’s founder, a minor celebrity in Hong Kong.

When customers stopped buying books, the store extended its hours and stocked up on goods from Hong Kong — Calbee chips, shrimp snacks, a selection of chilled teas and CDs of popular Chinese artists. When Chinese musical acts came to Los Angeles, it started to offer concert tickets.

The most recent moneymaker is lottery tickets. In the Alhambra store, a counter along the wall offers a hard surface to scrape out scratchers and contemplate the luckiest numbers to play.

“This has helped a lot,” Ng says, tapping the lottery ticket machine.

NHK’s Hong Kong locations are still traditional bookstores. In America, Ng says, everything’s gone downhill since people started buying their books online.

Still, she’s never mourned the bookstore’s lost identity. There have always been more important concerns, such as putting her daughter through medical school and paying her employees’ wages. Selling books or running lottery tickets — it’s the same struggle to her.

“There’s nothing else to do,” Ng says. “This is what we have to do. If you don’t change, you die.”

::

On a recent weekday, two children run screaming around Duong’s bookstore as the last lesson of the day concludes.

“I’ll see you Monday?” the children’s mother asks.

“Yes,” Duong says, and smiles.

She chases the children around the store, helps shoo them into the car and waves as the car pulls away, betraying no exhaustion, though she has been working since sunrise.

Then she closes the door and lets a sigh escape.

The sign over Helen Duong’s bookstore reads Soyodo, the name of a onetime chain bookstore with locations throughout California. Her business card reads “Beijing Books.” But books have little to do with Duong’s business model, and she hasn’t sold any in a while.

Three years ago, when Duong landed at LAX with her daughter, they didn’t know anyone in the city. They took a cab to a subleased room that Duong found in a Chinese newspaper that day. She rented the bookstore, and for a while, she sold books, and everything was just as she had imagined it would be.

Then Duong lost her savings on a fake business opportunity. Both of her employees left. Book sales dropped off.

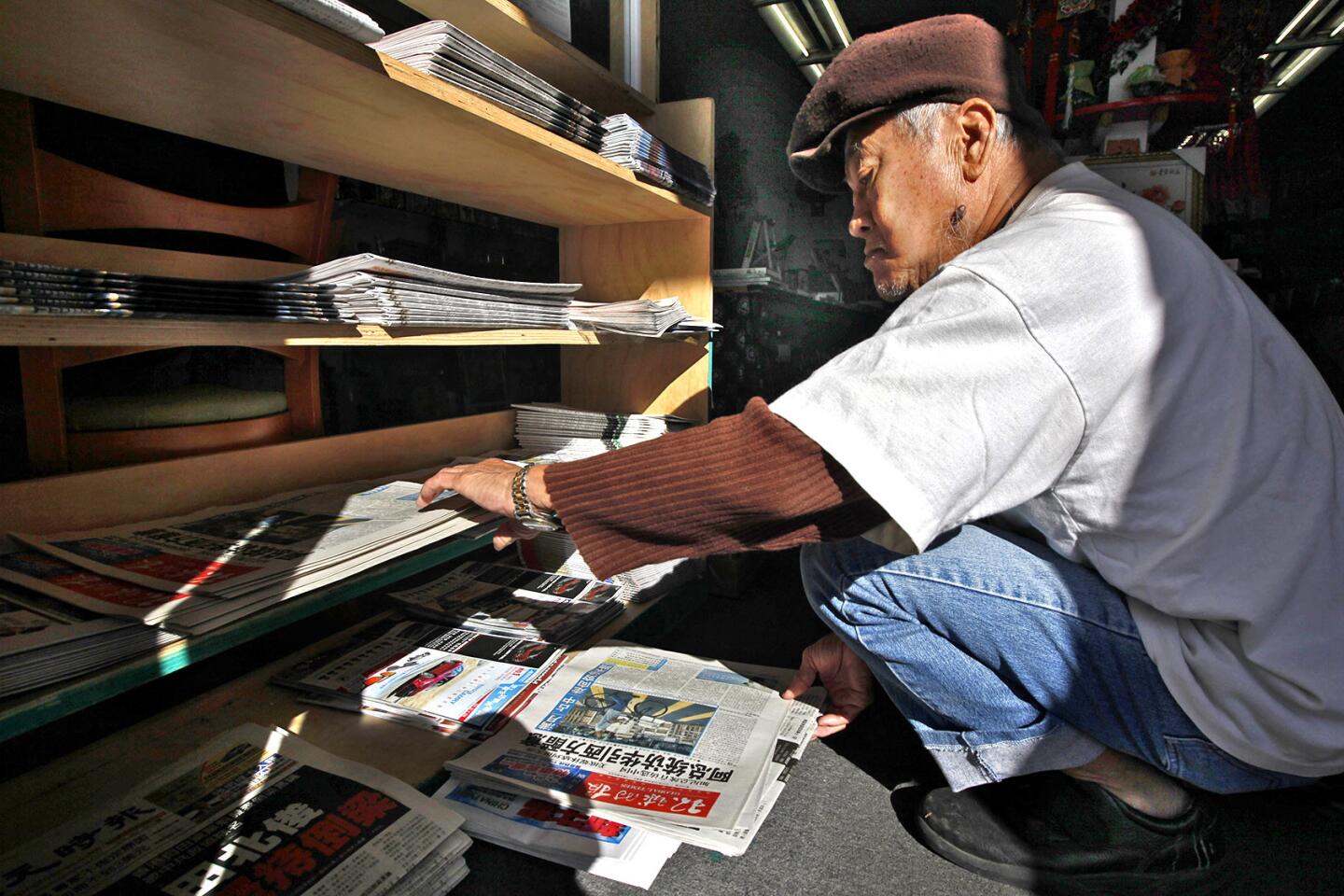

She started making friends, and slowly, her fortunes changed. She began to open the bookstore at 7 a.m. to sell newspapers and brewed tea for customers as they read at her table. Her regulars helped her run the shop in the mornings as she tidied up, and some offered her side jobs. She translated for new arrivals in America, tutored and helped match roommates to subleases. If gratitude came in the form of money, she accepted it — but only after protesting.

“People have been very good to me,” Duong says. “Kindness, that’s better than any kind of sales.”

She works 12-hour days, opening and closing the store by herself. She still sees America as a place where hard work pays off. She tries not to think about her lost savings. In the mornings when she opens the shop for business, you can hear her sing.

“When you come to America, you have to start over,” she says. “I’m not afraid to start over.”

Twitter: @frankshyong

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.