In quest to raise $6 billion, USC runs a massive fundraising machine

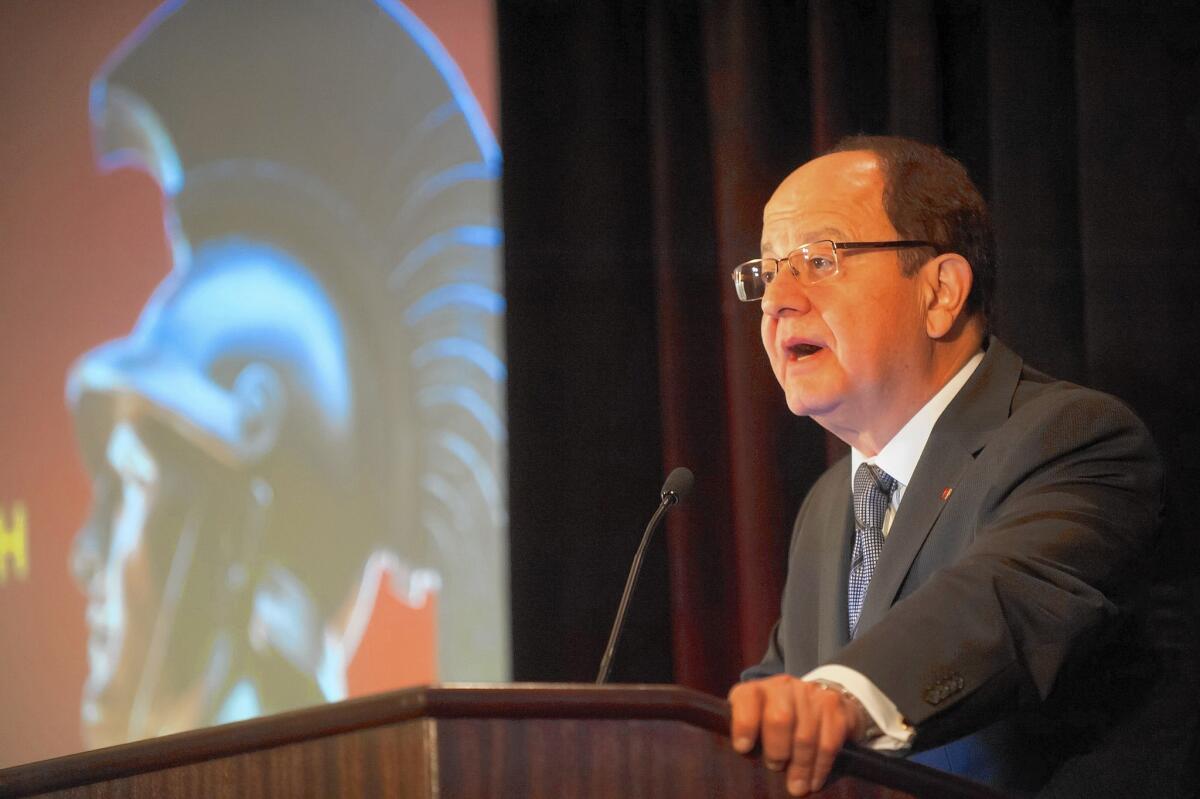

USC President C. L. Max Nikias addresses a crowd of alumni on a 2015 fundraising trip to Austin, Texas.

- Share via

Reporting from Austin, Texas — USC President C. L. Max Nikias was 1,400 miles from the Los Angeles campus, but he knew just how to appeal to his audience.

In a swanky hotel ballroom, he told the crowd of alumni and donors that Texas had become the largest feeder of students to USC after California, and that students from their state scored significantly higher on the SAT than the average of all applicants. Then he introduced Texas’ first lady, Cecilia Abbott, whose daughter will attend USC in the fall. That, he joked, could cause conflicts for the governor’s family during football games.

The three-day, three-city Trojan sprint through Texas was underway, one that could help USC raise the $1.8 billion it needs to reach its ambitious $6-billion campaign goal for scholarships, faculty hiring and building by the end of 2018.

“We love Texas,” Nikias told the crowd. It was part of a stump speech he delivered in Houston and Dallas. And beyond the Texan patriotism, it echoed many other talks he’s given around the country, and the world, about how the private university has become a respected research institution.

Under Nikias and his predecessor Steven Sample, USC has shed its derisive stereotype as the University of Spoiled Children and risen significantly in admissions selectivity and academic rankings. It has lured top faculty from such places as UCLA and Yale University, and attracts students from around the globe.

In two decades, it has climbed from 51st to 25th in U.S. News & World Report’s rankings of national universities.

Behind that success is an elaborate and powerful fundraising machine that extends from downtown Los Angeles to China, India and beyond.

An eye-popping 450 people work on the university’s fundraising team, double the staff from four years ago when the current campaign began.

They meet with philanthropists and the leaders of foundations and corporations that support higher education; some work like detectives, researching potential donors’ portfolios and ability to give, tracking property holdings, corporate disclosures of large stock purchases and career advancements. Others help arrange the wide-ranging travel of Nikias and the deans of USC’s individual schools — to places like Hong Kong, Mumbai, Sao Paulo, Washington and New York — to meet alumni and parents.

The efforts have paid off in a big way.

At $732 million, USC ranked third among U.S. colleges, behind Harvard and Stanford, in the actual cash donations it collected last year, according to the Council for Aid to Education. In the late 1990s, USC ranked as low as 16th. Increasingly, the university’s schools, departments, faculty chairs and buildings bear the names of donors — part of a carefully priced strategy that officials say encourages even more gifts.

Some skeptics, on and off campus, say that USC and many other large American universities have taken on a corporate flavor that emphasizes fundraising in unseemly ways. But others say there is no alternative to a massive money campaign if a university like USC is going to thrive. In fact, experts say, USC’s $4.5-billion endowment is considered small for its ambitions, dwarfed by Harvard’s $35 billion and Stanford’s $21 billion; competitors such as Northwestern University and the University of Notre Dame come in at $9.7 billion and $8 billion, respectively.

“A generation ago, USC was a very good regional university. Today it’s a world-class institution and, among other things, it took money to get there,” said Terry Hartle, senior vice president at the American Council on Education. Most academics around the country, he said, believe that USC “has come a long way in a very short period” and that only NYU has made a similar ascent in the same time.

In trying to raise money, even in this era of social media, it seems that nothing trumps old-fashioned face time with the university leader. So Nikias, his wife and an entourage of about a dozen flew to Houston in late April and then drove nearly 400 miles — from hotels to restaurants to private homes— to wave the Trojan flag in Longhorn country.

Albert Checcio, USC senior vice president for advancement, likened it to a tour by country rock musicians, complete with sound checks and show times. But instead of roadies, the show was staffed by conservatively dressed alumni office employees. And rather than a band, the star attraction was a former engineering professor with a Greek Cypriot accent.

Tours like this “keep people connected, and people who are connected are the people who are supportive,” Checcio said.

Going into the Texas events, USC leaders reviewed briefing books with details on how much some audience members have donated to the campus in the past, as well as their professional accomplishments. Nikias said that helps to spark conversation on the reception line and at smaller dinners. Although some showmanship is required, Nikias said, it is more important to know your audience and to be authentic.

“You cannot fake it,” he said.

In Houston, standing behind a bouquet of Trojan cardinal and gold roses, Nikias delivered a half-hour speech touting the campus — it admitted just 18% of applicants, and freshman SAT scores for the incoming class are in the top 10% nationally. The crowd cheered when he recounted how USC recruited top neuroscientists from rival UCLA, and audience members seemed impressed by a video showing plans for the $650-million University Village of dorms, classrooms and shops north of the main campus.

Of course, Nikias also spoke of money.

He recalled having to surmount skepticism when the $6-billion goal was announced. At the time, it was the largest campaign in American higher education; it has since been topped by Harvard’s. Nikias said that 240,000 of the 270,000 donations so far have been for $1,000 or less; 27, including one received after his Texas trip, were at least $25 million, and four of those were $100 million or more.

Nikias and his wife, Niki, hosted a private dinner at an Austin restaurant for 18 guests. With so many donations in hand, finding enough others in the next 3 1/2 years means “it’s not the time to relax … and I don’t want to celebrate in any way... We’ve got to be constantly expanding or renewing the donor pool,” Nikias said in an interview.

Since he became president five years ago, Nikias has traveled extensively across the U.S. and overseas, hoping to make new friends for USC and reconnecting with old ones. Those trips are aided by the university’s recruiting and alumni offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai, Taipei, Seoul, Mumbai, Mexico City, San Francisco, Washington and New York. The university may open another office in Texas. (USC declined to divulge how many donations have come from overseas or to provide a state-by-state breakdown.)

The university has a board of trustees with 53 voting members, including many of the city’s most successful developers, bankers and foundation heads. The list includes DreamWorks’ Steven Spielberg, Tutor Perini Corp.’s Ronald Tutor and Annenberg Foundation CEO Wallis Annenberg.

And its corporate-like approach to fundraising — plus its use of money to attract star tenured researchers — has brought criticism. Some part-time faculty, who teach many of the school’s undergraduate classes without the guarantee of long-term employment, say USC cares more about donors than about them. As a result, a campaign to unionize those professors is underway; it is resisted by the administration.

In the Austin hotel ballroom, the crowd of 150 skewed on the younger side, reflecting the area’s high-tech and entertainment economy. After sharing some of his thoughts about the school’s higher academic standards, Nikias told them: “I’m adding value to your degree, and that’s why you have to give back to the university.”

Brian Lederer, 29, an alumnus who now is studying for a master’s in business administration at the University of Texas, was pleasantly surprised that he was not pressed to write a check that night. He had given small amounts to USC in the past, and Nikias’ talk impressed him enough to cement plans to give more after he pays down his student loans. The speech, he said, made people “realize where your money is going when you do give back. And it showed the importance.”

Sylvester Martin Shelton, 86, a retired documentary film maker who earned a master’s at USC’s cinema school in the 1950s, said the reception was “first-class.” But “in terms of opening my pocketbook,” he thought that Nikias pushed too hard and too long.

“It didn’t engender empathy,” he said. Still, Shelton said he would continue making annual gifts to the School of Cinematic Arts, which would count toward the campaign. Some other alumni were upset that the event concentrated so heavily on the sciences and business programs.

National experts said such trips have become common for many university officials and that big schools regularly employ similarly large staffs to conduct deep donor research.

Though USC is feeling the pressure to meet its campaign goal and would likely need large gifts to do so, it and other schools also want small donations from young alumni who may turn into mega-donors decades later, said Amir Pasic, dean of Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy and a former fundraiser at Johns Hopkins.

Checcio said that USC spends about 11 cents to raise each gift dollar, a percentage several national experts said was considered relatively low.

But he declined to say how much USC spends annually on fundraising, or how much the Texas trip cost. While Nikias flew first class, Checcio and other staffers flew in coach; much work was done by volunteers. “Everyone’s concerned about the costs,” Checcio said.

In north Dallas, USC officials hosted a select, affluent group.

Tom Hicks, a leverage buyout businessman who owned the Texas Rangers and part of the Liverpool soccer club in Britain, offered his 25-acre, French chateau-style estate for a cocktail party. He and his wife, Cinda, have business degrees from USC.

After a security check to enter the gated property, the 80 or so guests were greeted by the Nikiases in a formal lobby. The deans of USC’s engineering and business schools, who had private meetings with Texas donors that week, spoke one-on-one to guests.

Nikias delivered remarks informally from the top of the small staircase leading to the sunken living room. He made many of the same points he had during other stops on the trip, but did not directly mention fundraising. Only when a guest asked about the campaign’s progress, causing the audience to laugh, did he discuss the $6-billion goal.

In an interview, Nikias was asked whether some people might resent USC for taking dollars that could go to such other causes as fighting homelessness or supporting the arts.

He noted that donors are free to make personal decisions — and that there was a lot of wealth in the U.S.

“Nobody would argue against all the needs that exist around the world, or even in the L.A. Basin. But at the end of the day, I am the president of this university and I pledged to look after the very best interest of this university. So for me, I live and breathe USC.”

Whether the Texas audiences were ready to make large pledges remains to be seen. USC officials said they did not expect to snare any specific gifts, although clearly some donors were being identified for follow-ups in the months ahead.

“This personal touch and good will always pay dividends,” Nikias said during a stop for coffee. “One thing you learn in fundraising is that you have to be patient. You can never rush it. No doubt, there will be gifts from Texas.”

Twitter: @larrygordonlat

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.