Retiree benefits become a flashpoint in the battle between charters and traditional schools

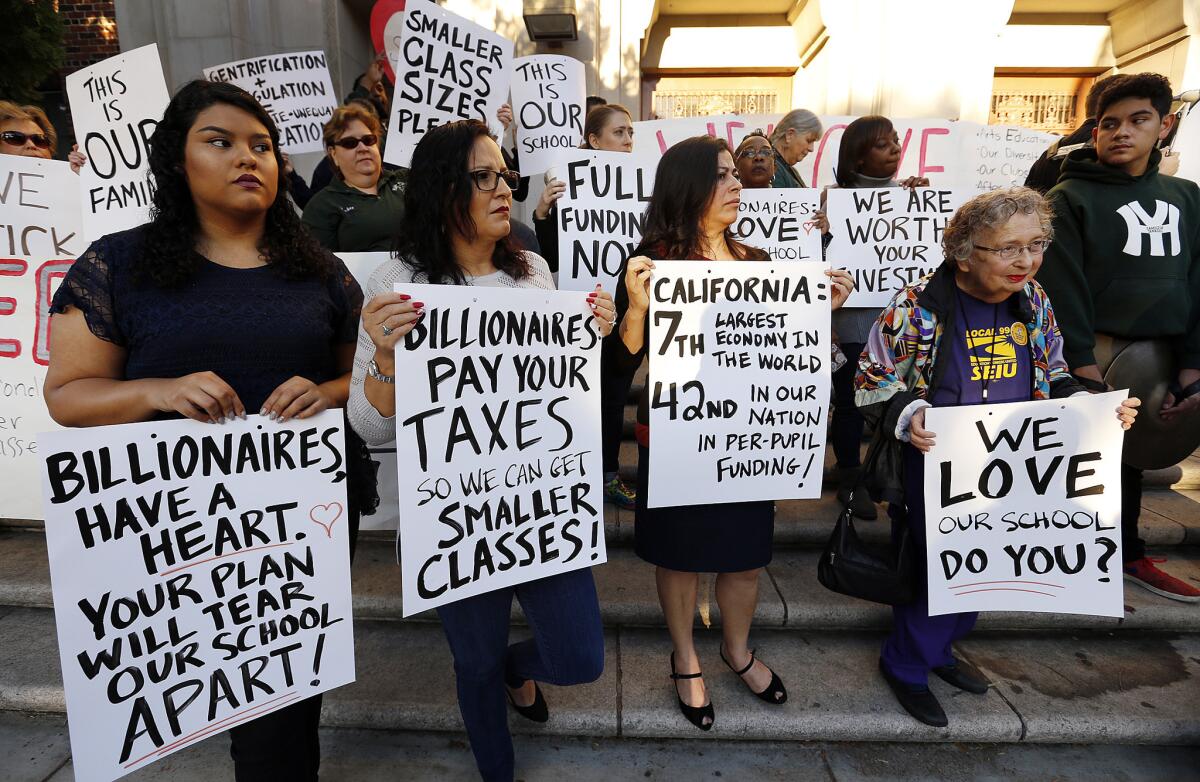

Students, parents and teachers take part in a February protest at Hamilton High organized by the Alliance to Reclaim Our Schools to oppose charter expansion.

- Share via

A Woodland Hills charter school recently made an unusual offer to its veteran teachers: We’ll give you $30,000 if you return to the Los Angeles Unified School District before you retire.

It wasn’t the teachers that El Camino Real Charter High School wanted to get rid of. It was the cost of their retirement benefits.

The school’s cost-shifting strategy is one of many flashpoints between traditional public schools and the independent charters they compete with for students and money.

In this case, it’s a battle over who should pay for an employee’s health benefits after retirement — the charter school or the larger school district.

Financial challenges are all-but-universal in the education world, and retiree benefits are particularly costly. L.A. Unified’s unfunded liability for employee benefits has escalated to $13.6 billion.

The El Camino plan would add from $2.5 million to $4.2 million to that deficit, based on district estimates. The idea is that teachers would spend their careers in the charter school, but later transfer to LAUSD to qualify for the huge institution’s retirement benefits.

Except the district has decided not to play ball.

Teachers who return to the district, simply to retire, are not entitled to district retirement benefits, general counsel David Holmquist said.

“This would be an obligation that in my view would be the charter’s responsibility,” Holmquist said.

Officials reached that determination Friday, and, if that decision holds, then the recent retirees would have to turn to El Camino for retirement benefits after all.

The dispute is notable in part because of an effort by advocates to sharply increase the number of charter schools in Los Angeles.

Under that proposal, at least 260 additional charters would open over the next eight years, resulting in about half of L.A. Unified School District students being enrolled in these independently managed public schools. These backers argue that more charters will give parents more choices and improve education in the city.

But opponents say a huge increase in the number of charters could push the district to the brink of insolvency by draining resources and leaving behind students who are the most difficult and expensive to educate.

Charters are independently operated public schools and exempt from some rules that govern traditional, district-run campuses. Most charters are nonunion, and are not bound to match district benefits.

But El Camino did not want its teachers to feel as though they were giving up something when the campus left district control five years ago. So teachers retained their union representation.

L.A. Unified and the teachers union also agreed to give El Camino teachers up to five years to return to the district.

“This is a charter school that did at least try to do right by teachers,” said Monique Morrissey, an economist at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, which is based in Washington. “It did put a premium from the get-go on retaining unionized, professional teachers rather than taking the low road — using low-paid, unprofessional, nonunionized teachers and churning through them.”

As the teacher’s five-year window to return to the district drew near, El Camino administrators concluded that it was now or never to lighten its retirement burden.

Teachers with 17 or more years of experience could get $30,000 if they left and retired through L.A. Unified rather than El Camino. Teachers with fewer years of service qualified for reduced amounts.

According to L.A. Unified, 10 individuals with teaching credentials have submitted paperwork to return to L.A. Unified. Eight of those also indicated that they plan to retire.

Other employees also were eligible for smaller buyouts. Two administrators and two nonteaching staff members took advantage, according to El Camino.

Whatever happens, El Camino remains on the hook for most of its workers, a potential liability of more than $40 million, said Chief Business Officer Marshall Mayotte.

For health and life sciences teacher Evalyn Kallman, the timing of the buyout was right. She started teaching in her 20s and has worked well over 30 years.

“Even if I work another few years,” she said, “it won’t make a significant difference in the amount of retirement I get.”

The district already is paying $1 billion a year— from a $7.1-billion budget for benefits to both current and retired employees. This number is expected to rise sharply with an older, longer-living workforce. And money to pay for these costs has been limited by shrinking enrollment — in large measure because of the growth of charters.

“I do think it’s unfair — the idea that we are saddled with this obligation when another employer is benefiting from the services,” Holmquist said of El Camino’s plan. Which is not to say the strategy’s wisdom is lost on him. “I think it’s a smart business decision on their part,” he said.

Twitter: @howardblume

Editor’s note: Education Matters receives funding from a number of foundations, including one or more mentioned in this article. The California Community Foundation and United Way of Greater Los Angeles administer grants from the Baxter Family Foundation, the Broad Foundation, the California Endowment and the Wasserman Foundation. Under terms of the grants, The Times retains complete control over editorial content.

ALSO

Sport Chalet will close all stores and stop online sales

U.S. agents find 140-foot tunnel under U.S.-Mexico border in Calexico

Non-Muslim woman caned in Indonesia chose the punishment over jail time

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.