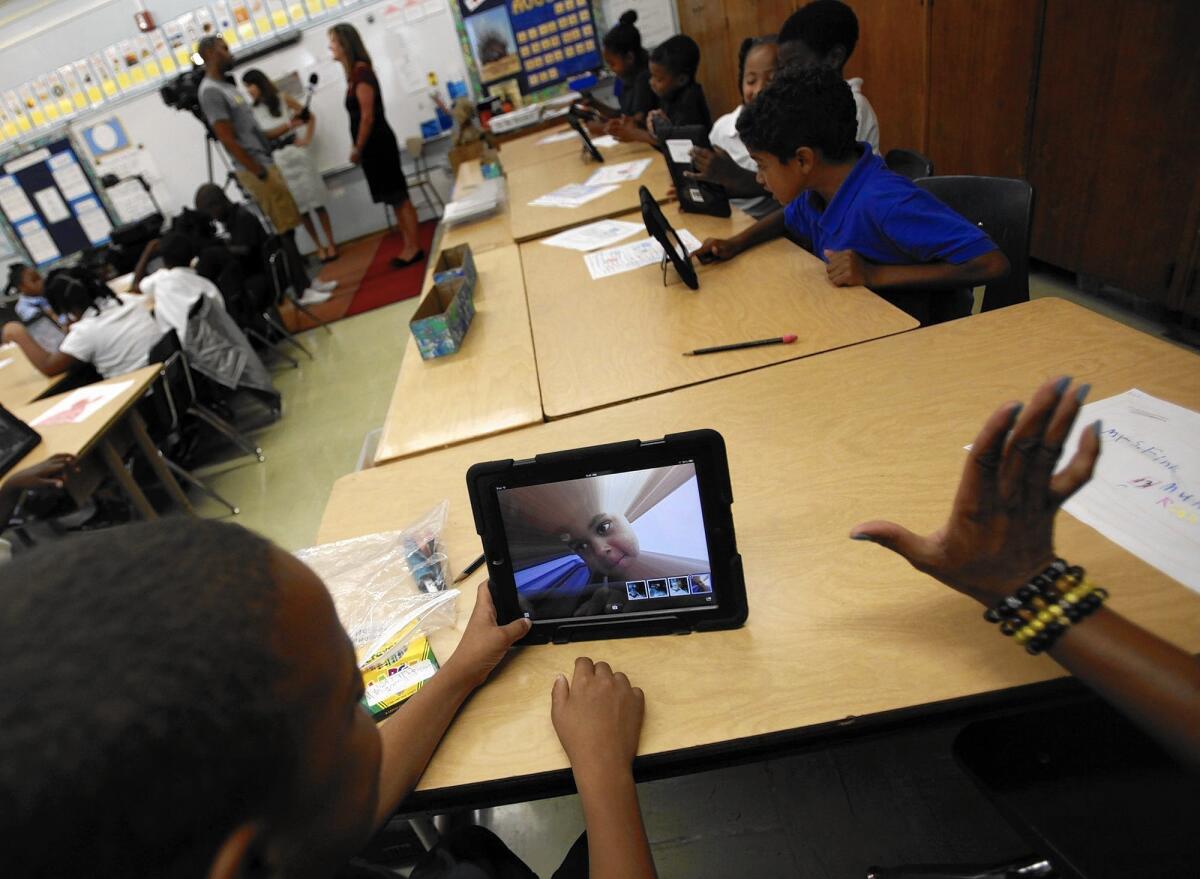

L.A. Unified’s iPad program plagued by problems early, review says

- Share via

A $1.3-billion iPads-for-all program in Los Angeles schools was plagued by lack of resources and inadequate planning for how the devices would be used in classrooms and, later, how they would be evaluated, according to a federal review.

The U.S. Education Department study found similar problems with a faulty student records system that launched at the beginning of the school year.

The troubled technology projects were a factor in the departure of L.A. schools Supt. John Deasy, who resigned under pressure in October. And they were largely responsible for the resignation, under threat of dismissal, of Ronald Chandler, former head of technology for the L.A. Unified School District.

The review was provided by the Education Department at the request of current Supt. Ramon C. Cortines. It offered a rare independent interpretation of events that have provoked controversy for more than a year.

The report found that L.A. Unified was too heavily focused on the iPad instead of being open to less-expensive alternatives. In addition, it concluded that teachers weren’t provided enough training and that senior managers were unable or unwilling to communicate concerns and address issues before they became serious problems.

“Among the most significant gaps we identified was the absence of district-wide instructional technology leadership,” the report stated. That conclusion referred both to the absence of a replacement for Chandler as well as past management of the effort.

The technology project was a signature initiative of Deasy: In a speech to administrators in fall 2012, he announced plans to provide a tablet to every student. L.A. Unified had only several months to put together the program, which went out to bid early in 2013.

Deasy was motivated to move fast. He had concluded that the mastery of technology — and devices like the iPad — was the future of education. He did not want L.A.’s low-income and minority students to be left behind. Additionally, California was switching to computer-based standardized tests and he wanted L.A. Unified to be ready.

But the massive bureaucracy was not well-organized for a quick turnaround. Facilities chief Mark Hovatter, for example, was not included in the early planning despite the fact that school networks would need massive technology upgrades.

Critics also questioned the use of school construction bond funds to pay for both the iPads and the expensive curriculum on them.

The rollout at 47 schools in fall 2013 had problems from the start. Teachers were ill-trained, schools had spotty Internet connections and students quickly bypassed security filters. Under mounting pressure, Deasy agreed to slow down the effort. The district has since moved away from Apple, maker of the iPad, as the exclusive provider.

Even now, according to the federal report, “some schools receiving devices ... have not developed plans for how the devices will be used to support learning.... As a result, there is no common vision for how devices should be shifting learning and teaching within schools, making measuring impact difficult, if even possible.”

Beyond the lack of instructional planning, there was no framework for determining whether the project was successful, making it “difficult to show the impact of the investment or know which pilot practices should be scaled across the district more widely.”

In addition, schools weren’t receiving enough ongoing help in conducting lessons with the devices, the report said.

The evaluation also found the district too “heavily dependent on a single commercial product for providing digital learning resources, which has plagued the project since the initial rollout.”

As a result, L.A. Unified had overlooked lower-cost and even free resources that could have saved money. And officials did too little to assist teachers in developing and sharing their own digital lesson plans.

“The Department of Education had a number of common-sense suggestions ... such as better planning, better testing and evaluation of technology, and better training,” said school board member Monica Ratliff, who chaired a panel that reviewed the technology project last year. She produced a report that raised issues similar to those of the Education Department, but it was discounted by some Deasy allies as unfair to the superintendent. (The federal agency is headed by Arne Duncan, a longtime admirer of both Deasy and Cortines.)

In her report, Ratliff also asserted that there was an appearance that Apple and Pearson, which provided the curriculum, were destined to win the contract from the start. This impression was reinforced, in the view of critics, by a series of emails that subsequently came to light. They suggested that Deasy and a senior deputy had developed an especially close working relationship with executives from Apple and Pearson before the bidding for the computer contract.

The iPad program remains under review. The FBI has subpoenaed documents as part of a criminal investigation. And L.A. Unified’s inspector general is completing an assessment of the bidding process at the request of the Board of Education.

Deasy, meanwhile, has defenders who insist that his critics undermined a vision for technology that could have succeeded had officials stayed the course. Deasy was not available for comment Monday. He has accepted a consulting position at the Broad Academy, which offers training for school district leaders.

Chandler also has supporters, who view him as a scapegoat for factors beyond his control. Chandler could not be reached Monday.

The federal review, overseen by Richard Culatta, director of the Office of Educational Technology, was given to board members last month. It was publicly released on 4LAKids, a blog written by Scott Folsom, who serves on a committee overseeing school bond spending.

Twitter: @howardblume

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.