He’s getting into college without the help of wealth and privilege — and it’s hard work

- Share via

On the mantel in a South Los Angeles home, the lovingly arranged keepsakes reflect a family’s pride.

Damion Lester Jr. smiles broadly in his senior class portrait, decked out in the blue cap and gown of nearby George Washington Preparatory High School. His certificate of high honors for his A grades is nestled near his football awards and homecoming king crown.

The achievements have impressed colleges, and the first offers of admission have come in: UC Davis and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas so far, with word from other schools still to come. He was not admitted to UCLA, a top choice.

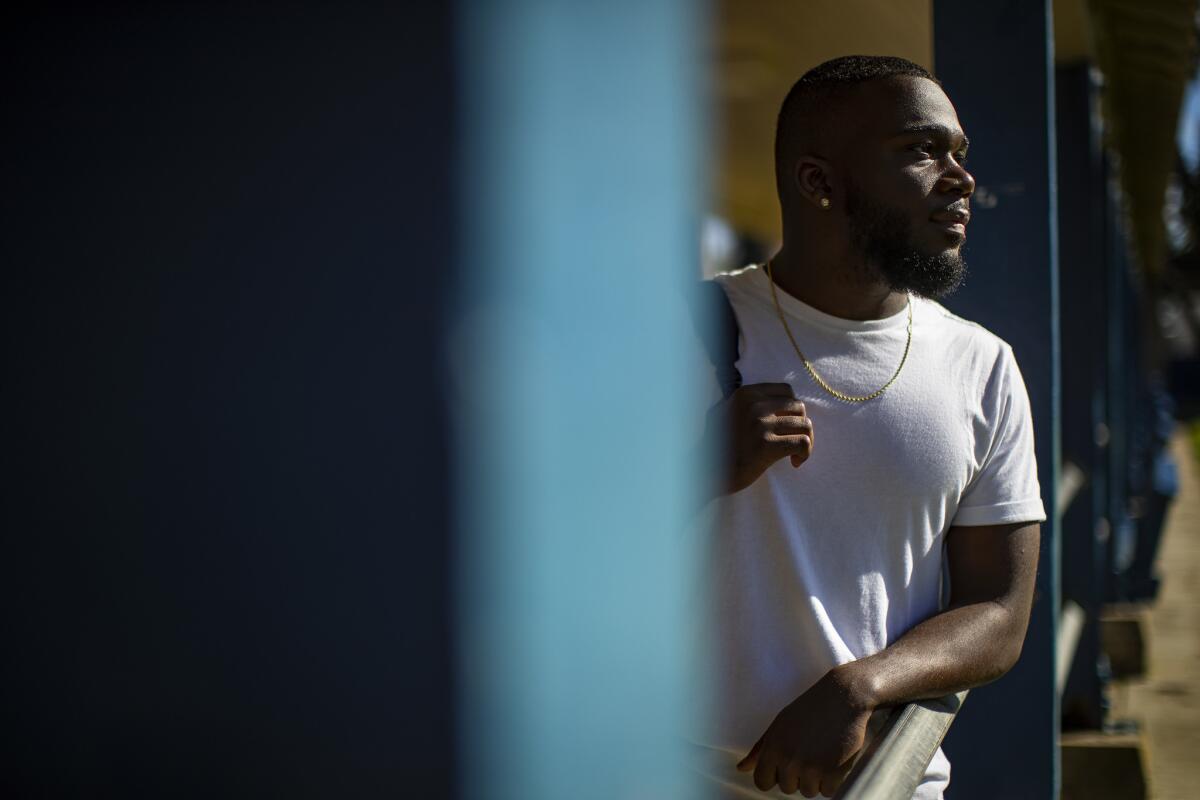

Lester, 18, is getting into college without the advantages of privilege or wealth.

His daily reality is worlds away from those described in the college admissions scandal, in which wealthy parents allegedly paid to fake and bribe their children’s way into top universities.

Lester lives with his grandparents near Watts in Vermont Vista, which ranks third in violent crime among more than 200 L.A. neighborhoods mapped by The Times. The median household income in the predominantly black and Latino neighborhood is $31,000. Only 6% of adults have four-year college degrees.

The high school student aims to beat those odds. He will graduate as class valedictorian in June. And if he can scrape together enough financial aid, he will be the first in his family to attend college.

Lester’s grandfather joined the military after high school and now works as a janitor. His grandmother got pregnant as a teen and dropped out of school. His father got tangled up with gangs and spent six years in prison, Lester said, while his mother also had troubles with the law. They lost custody of their son when he was 3 years old.

Under his grandmother’s watchful eye, Lester managed to avoid the gangs, dodge the street shootings and steer clear of drugs. For him, college is not about parties and game days, as one rich USC student caught in the scandal said in a video. It’s a way out of neighborhood poverty and crime.

“I know my job is to do well in school so I can have better options for myself,” Lester said. “Not being on government assistance … being able to move up.”

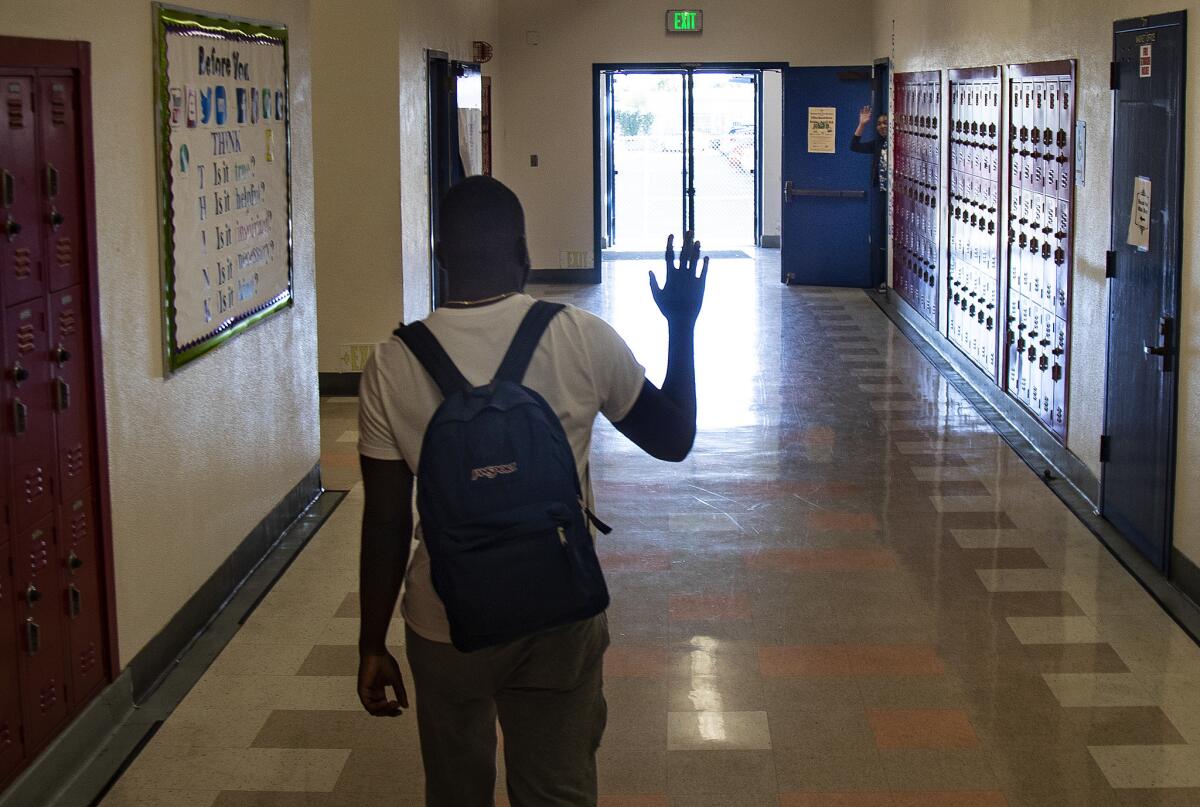

On a recent day, Lester arrived at school just before 8 a.m. to make the morning announcements as student body president, walking past lockers and halls painted in Washington Prep’s patriotic red, white and blue. He gave fist bumps and hugs to his classmates, who voted him class president four years in a row.

Alexina Coleman, a senior, said Lester was one of the first to befriend her when she transferred to the school last year.

“No one has a bad thing to say about Damion,” she said.

On this day, Lester had his usual full academic schedule — creative writing, AP government and AP English literature — and seemed not to waste a minute. He spent some time on the yearbook, where he is designing pages. One photo shows the school’s top 10 scholars. Lester, who cut his dreadlocks and pierced his ears a few months ago to change things up, is the only African American among them.

“Just because of my race doesn’t mean I can’t achieve,” he said, sizing photos and tweaking colors and fonts.

For his leadership class, he strode through campus to pin down logistics for an upcoming celebration of school athletes and collect money for a fundraising campaign for cancer research.

In one classroom, he shook a donation box and flashed his charismatic smile. “Anybody? Ah, there we go,” he said, as students pulled out coins.

Principal Dechele Byrd and her staff have worked hard to build a college-going culture. But it’s hard, she said, to keep up with the more affluent.

At private Harvard-Westlake School, for instance, nine deans work with about 900 students from sophomore through senior year to help them with academic and college counseling. Three-quarters of the 210 full-time faculty have master’s or doctoral degrees, according to the current school profile.

The Studio City school offers 28 AP courses and spring college tours for juniors. Last year, students won admission to Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, Brown, University of Pennsylvania, University of Chicago, UC Berkeley, USC.

At Washington Prep, Byrd finally was able to hire her first full-time college counselor for her 800 students last fall using a three-year grant from the Los Angeles Unified School District; she’ll have to scramble again for money when it runs out. She’s also managed to find funding for four full-time academic counselors. Just over half of her 41 full-time faculty have graduate degrees. The school offers 12 AP courses.

Byrd’s students rely on free tutoring from sources such as the online Khan Academy, as well as academic support from nonprofit organizations, USC, UCLA and L.A. Southwest College. L.A. Unified also has purchased online college prep software for all schools and, for the first time this year, covered SAT test fees for all juniors.

“It’s disheartening to see people with so many financial resources using their privilege in negative ways to give their children an edge,” Byrd said of the parents involved in the admissions scandal. “We have to rely on free resources. But our students are extremely resilient in pushing forward despite their circumstances.”

Few more so than Lester, school staff say. After his last class, he bounded into the college counseling office to check on scholarship opportunities. Marcy Zaldana, the counselor, told him about a new one and offered tips on how to apply.

“Good luck, Damion, you got this,” she said. “I believe in you.”

Zaldana has high hopes for Lester’s college future, despite his dismal SAT test results, which ranked below the 10th percentile. (He has no money for pricey test prep books or courses — and no one is taking his tests for him, as people are alleged to have done for rich students in the college admissions scandal.) She says his 4.1 grade-point average shows ambition, diligence and extraordinary perseverance under challenging life circumstances.

“With his grades, you can see everything is possible,” she said. “He’s an overachiever. He goes after opportunities. He knocks on doors and they open.”

Lester’s drive took root slowly. He flunked first grade and had to overcome a strong stutter that made him terrified to read aloud in class.

A fifth-grade teacher saw Lester’s potential and urged his grandmother, Linda Reedy, to send him to a magnet program at a middle school outside the neighborhood. There, he says, competing with high-performing students — and initially failing to best them — fired his competitive spirit. Meanwhile, his father had been released from prison, started a new life in Las Vegas and told his son that gangbanging didn’t pay off.

“All I can really say is that I had an epiphany. I said, ‘Damion, you gotta kick into action.’”

In high school, he started to ace classes and grew fascinated with history, compiling a personal library of nearly 40 books — on ancient Mesopotamia, Marco Polo, Genghis Khan, Sir Francis Drake.

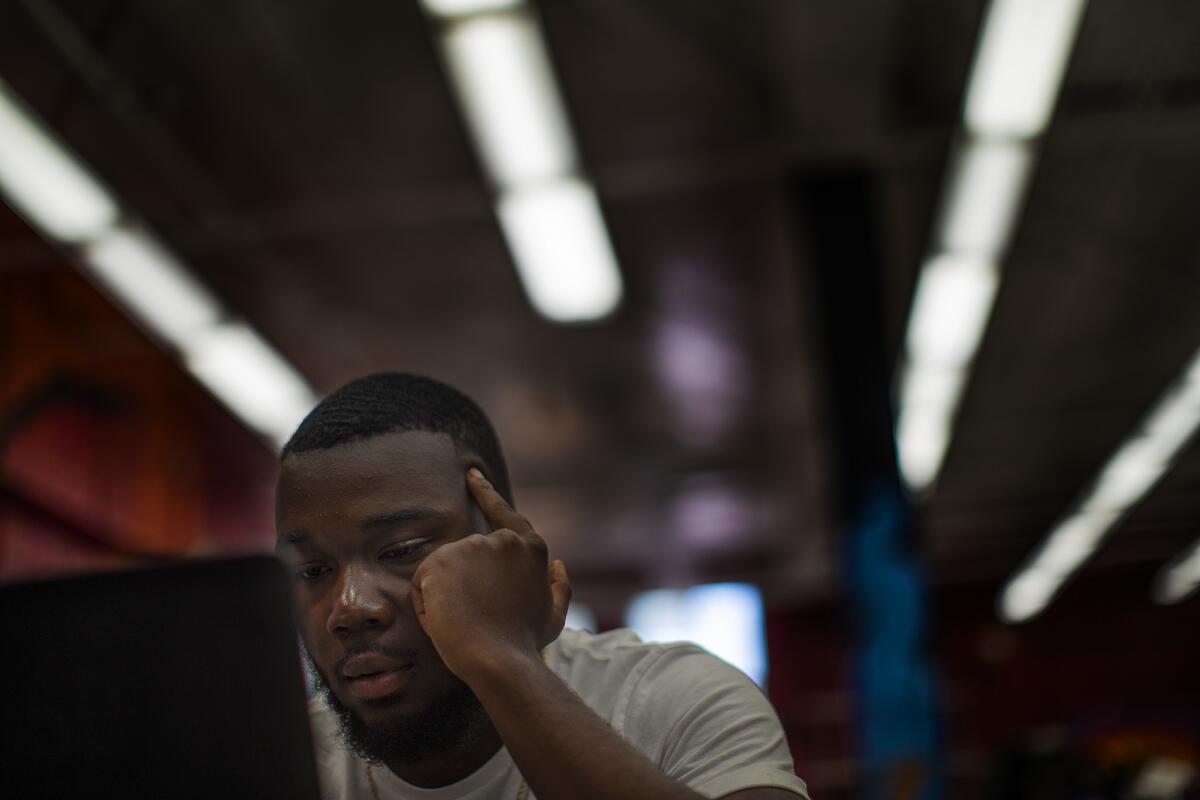

Now he’s turned to new interests both to express his creativity and make money for himself and his family. He creates beats for rap artists he networks with on social media, livestreams and voices video games — at the moment, a SWAT officer and a zombie survivor.

“It’s making money the right way,” he said.

He recently demonstrated his voices on the computer he assembled a few years ago. He can do a Jamaican lilt and a Southern outlaw. He starts his monster growl, scowling and pushing in his face with his fists, but burst out laughing midway through.

He records in his closet, which he padded with foam and closed off with a heavy blanket.

He livestreams on Twitch, chatting about pop culture, college and dispensing life advice. The other day, while he was live, a follower wrote that he was going for his first job interview.

“Wear a long sleeve, man. Be as respectful as possible. Knock it out of the park,” Lester said, giving him a virtual fist bump.

Donations from his 4,714 followers have helped him raise about $7,000 in the last three years, he says, covering family health bills, his microphone, double monitors, computer parts, a keyboard and a set of weights.

But he and his family don’t have the kind of money needed for college — because even with financial aid, he’ll still need thousands for housing, food and other expenses.

Family conflicts, financial stress, the crush of his studies and others’ expectations all came to a head last fall. He told Byrd he wasn’t going to college. She and other staff told him he was.

In November, he had a meltdown, punched his bedroom wall — and broke his right hand. A resulting bone and blood infection put him in the hospital for more than a week.

He says the enforced rest gave him time to regroup. “Things had to get worse before they got better. I realized I have to stay strong.”

As he awaits word from colleges, he is philosophical about the scandal in the news. Karma will bite hard on those who do wrong, he says with a shrug. He’s focused on his dreams: meeting a wife in college, raising a family with two or three kids, landing a good job with decent pay in a safe neighborhood.

“Love, family, friends,” Lester said. “Those things make me feel good.”

Twitter: @TeresaWatanabe

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.