Thrust Faults Pose Brutal Danger to Basin

- Share via

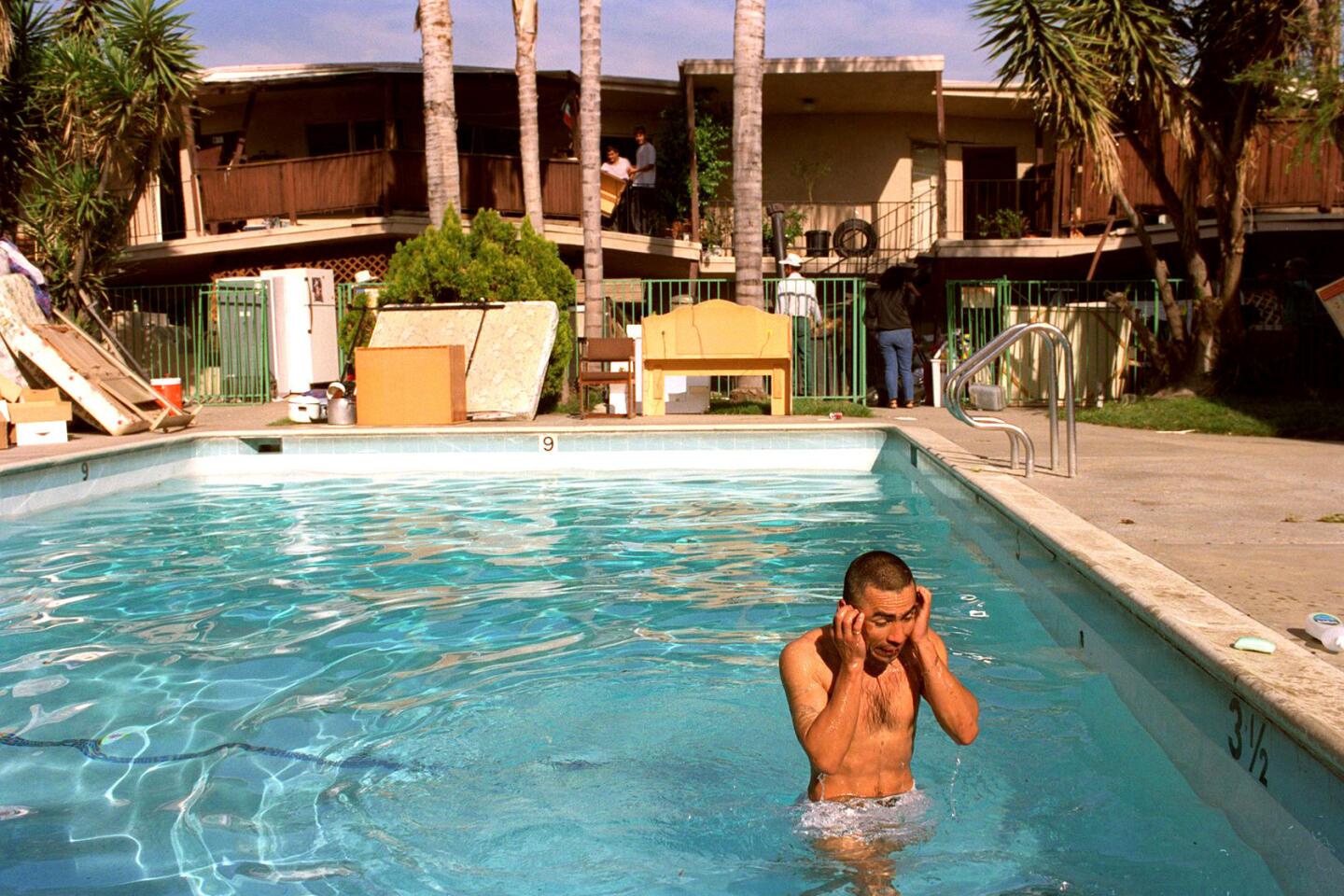

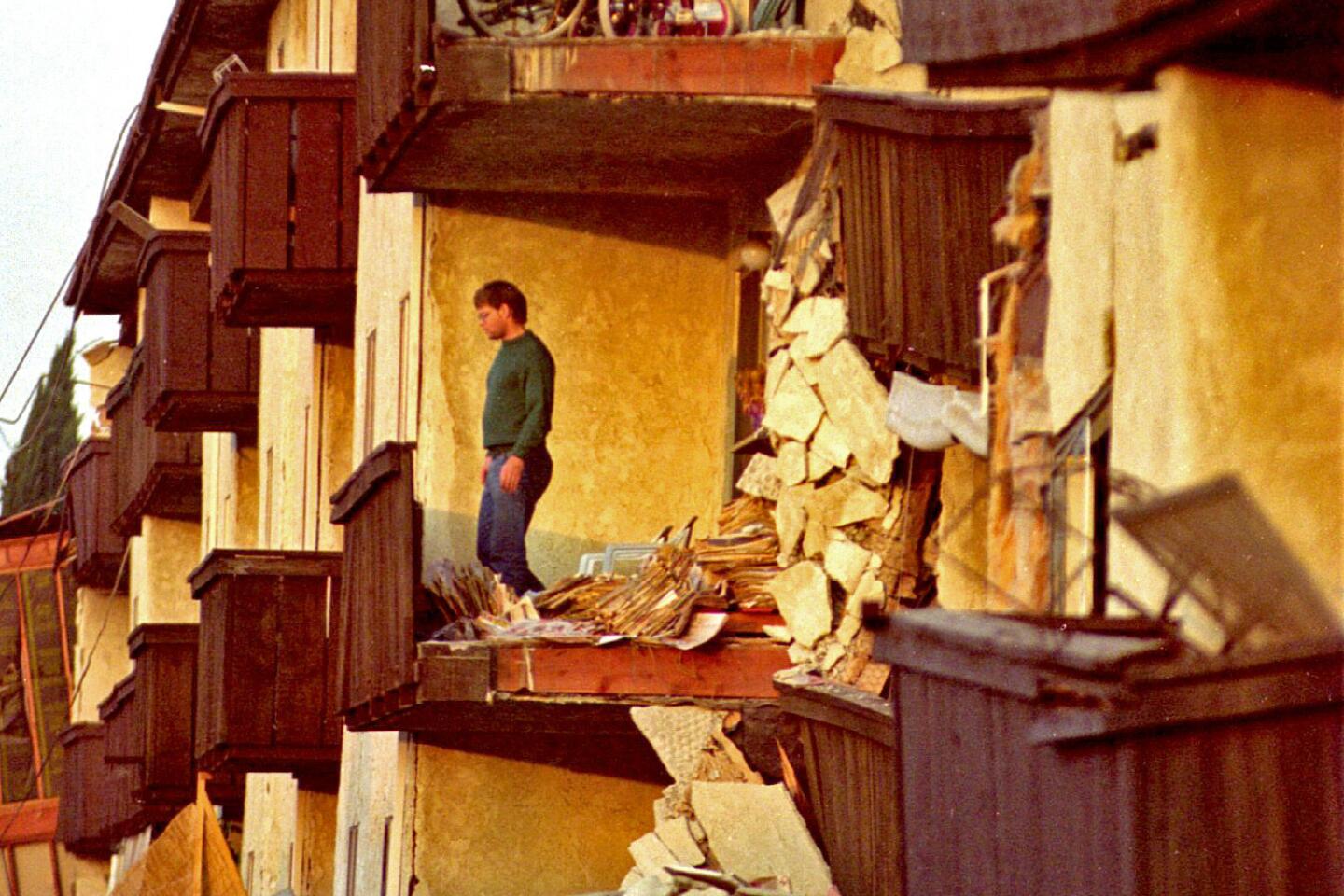

The earthquake that convulsed the San Fernando Valley early Monday demonstrated as brutally as possible the danger posed by a complex web of deeply buried thrust faults underlying the Los Angeles Basin.

Seismologists said Monday that dozens of such faults underlay the basin, many unmapped and unknown until they abruptly announce their presence with a powerful shudder. Although they may lack the capacity to generate the devastating force of the Big One, these faults can cause severe injury and widespread property damage.

“There are so many (faults) that can produce stress of this magnitude,” said Hiroo Kanamori, director of the Caltech Seismological Laboratory. “We have to be prepared for this sort of thing.”

Monday’s 6.6 quake, the strongest in the basin’s modern history, was powerful enough to raise parts of Northridge, the Northridge hills and the Santa Susana Mountains “a foot or two,” while areas of the northeast Valley south of the city of San Fernando slumped an equal amount, said Lucille M. Jones, a seismologist at the Pasadena field office of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Movement on the fault may have been as much as two yards on each side, several seismologists said.

Any of the other short, thrust faults hidden under the basin could produce the same kind of strong, jarring upward motion. A thrust fault, unlike the more common horizontal strike-slip fault, moves vertically.

Within hours of the frightening, early morning jolt, scientists from around the state headed for Southern California to study the Northridge earthquake, and portable seismographs were installed through the quake area.

As they carefully evaluated their seismic charts and the results of preliminary aerial surveys, scientists started to construct a rational frame of facts and measurements around Monday morning’s long seconds of tumult.

By late afternoon, scientists had yet to determine which fault was responsible for the damage. They hoped that the pattern of aftershocks would help them locate it more precisely and give a clearer insight into the stresses that underpin the region.

Monday’s quake lasted no more than 10 seconds at its source, with up to an additional 20 seconds of reverberations elsewhere. That was followed by more than 86 noticeable aftershocks, including three of at least 5.0 in magnitude by Monday night. The strongest was a 5.3 jolt.

Aftershocks are expected to continue with some decreasing frequency through the coming months, scientists said. The chance of an aftershock of more than 5.5 in magnitude in the weeks ahead is 1-in-4; and for an aftershock of 6.0 or more in the coming year is 1-in-10, they said.

“The fault is still uncertain,” said Pat Jorgenson, spokeswoman for the Geological Survey office in Menlo Park. “Anybody who’s going on a limb and identifying a fault is not being cautious.”

The quake occurred on what Jones, Kate Hutton of Caltech and other scientists initially said was an unnamed, virtually unknown fault on a plane shallowly dipping toward the Santa Monica Mountains.

They believe that the fault probably intersects with the Elysian Park Fault belt, which extends about 50 miles from Whittier all the way to the ocean near Point Dume. That fault generated the powerful Whittier Narrows thrust quake of Oct. 1, 1987.

But one of Caltech’s most prominent seismologists, Kerry Sieh, said late Monday afternoon that there is at least a chance that the quake occurred on the Elysian Park Fault itself. The fault intersects with two others near Reseda and Roscoe boulevards, about a mile south of Cal State Northridge, which was severely damaged Monday. Those two faults, called the Devonshire and the Frew, had been mapped years ago by oil company geologists.

The quake could have begun on any of the three, Sieh said. Not until the aftershock pattern is further studied will scientists know which.

Jones and Hutton noted that almost all of the aftershocks occurred well north of the Elysian Park Fault (sometimes also known as the Santa Monica Mountain Thrust Fault). The two scientists continued to favor one of the lateral faults, probably the Frew.

Jim Mori, director of the Pasadena field office of the USGS, said the quake was on “an east-west trending thrust fault with the aftershocks to the north.” Based on this, he said the Elysian Park Fault was not directly involved. A helicopter flight by Sieh and another Caltech seismologist, James Dolan, Monday morning showed no indication of a ground rupture from the quake. This was also the case with the magnitude 5.9 Whittier Narrows temblor and is the trademark of a deeply buried fault.

After Whittier Narrows, some scientists said the quake danger in the Los Angeles Basin had been underestimated. There may have been some past quakes that were unknown, they explained, because they did not break the surface.

Seismologists at Caltech and the USGS said they were certain that the Northridge quake was not a foreshock of a great quake on the San Andreas Fault, at least 25 miles away. The quake was believed to have done nothing to relieve pressure on the San Andreas, but did nothing to add to it either, earthquake experts said.

Tom Henyey, director of the Southern California Earthquake Center at USC, met with USGS scientists in Pasadena to develop a request for federal funds to study the temblor, a USC spokesman said.

Destruction From Below

The earthquake that snapped Southland homes and highways like plastic toys is thought to have been triggered by one of three faults some nine miles beneath the surface.

The Facts

Time: 4:31 a.m.

Magnitude: 6.6, with aftershocks above 4.5

Duration: approximately 30 seconds

Epicenter: San Fernando Valley, one mile south of Cal State Northridge

Moving mountains: Monday’s quake pushed the Santa Monica and San Gabriel mountain ranges higher and closer together, making the San Fernando Valley slightly narrower. Geologists will determine the extent of the movement within the next few days.

Impact on San Andreas: The quake is said to have done nothing to relieve pressure or trigger activity along the nearby San Andreas Fault.

Ranking the Big Ones

Here’s how the Northridge quake compares to other major quakes in California and Mexico: 1906 San Francisco: 8.3 1985 Mexico City: 8.1 1992 Landers: 7.6 1989 Loma Prieta (San Francisco): 7.1 1992 Big Bear: 6.7 1971 Sylmar: 6.4

Quake’s Starting Point

Believed to have occurred along one of three faults that run, like spokes of a wheel, from the epicenter.

The Elysian Park fold and thrust belt is believed to be part of a network of deep-seated faults. The Elysian Park system produced the 5.9 Whittier Narrows quake in 1987.

Sources: Cal Tech, Associated Press

Researched by Janice L. Jones/Los Angeles Times

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.