Many poorer areas of L.A. get less trash service, analysis shows

Residents in Northeast, Central and South Los Angeles received worse service for illegal dumping pickup than other parts of the city, a Times analysis found.

- Share via

On an overcast May morning, city workers picked up abandoned tires, charred furniture and soiled clothes from an alley in South Los Angeles.

Neighbors said it was the first time they had seen a city sanitation crew visit the alley off East 108th Street in more than a year. One resident said nails punctured all four tires on her sedan after she drove through. Another paid a contractor to clear the entrance of a blocked driveway.

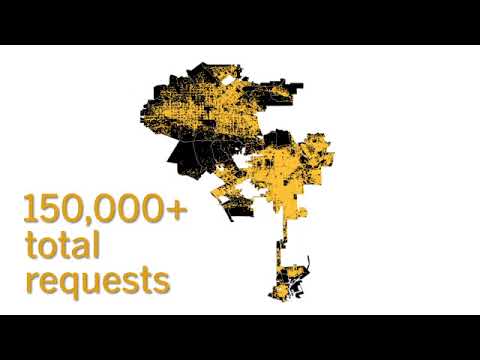

Their complaints point to a broader problem with what many consider to be a basic government service. Since 2010, sanitation crews failed to respond to more than 20% of Los Angeles residents’ requests to remove illegal refuse from sidewalks and alleyways, a Times analysis has found.

The data show that residents receive dramatically different levels of street-cleaning service depending on where they live: More than one-third of pleas to remove refuse from dozens of neighborhoods in Central, Northeast and South L.A. were ignored even as sanitation workers responded to 99% of requests in other parts of the city.

While some wealthy areas suffered from poor service, the majority of neighborhoods with unmet requests were low-income.

For example, Venice generated a similar number of trash-pickup requests as Pico-Union, but less than 60% were completed in the central city neighborhood, compared with nearly all requests in the affluent Westside hot spot.

Before the sanitation crew visited the East 108th Street alley in May, the alley had provoked 20 cleanup requests since early 2014, with just two completed during that time, city records show.

“I’m just accustomed to the disparity of service,” said Ron Smith, a longtime resident of the surrounding Green Meadows neighborhood. “It goes beyond service. People understand that certain lives are more valuable than others. The Westside gets more attention and other sides don’t. But I refuse to accept that.”

In response to The Times’ findings, Mayor Eric Garcetti said in a statement Friday that he would launch an internal investigation into all outstanding service requests related to illegal dumping.

“I am disappointed to learn that, despite our efforts to directly address inequities, service response times are unacceptable in parts of the city where the demand for service is highest,” Garcetti said. “Whether it is a breakdown in technology or a backlog from years of neglect, we must do better.”

Garcetti said he would direct technology staff in his office to “clear the backlog and reduce service response times immediately.” The mayor noted that his “Clean Streets Initiative,” a program launched this spring to prioritize cleanup efforts, is intended specifically “to ensure that our highest level of service is directed towards our highest need neighborhoods.”

Since taking office in July 2013, Garcetti has touted a “back to basics” agenda, and gave top priority to core services that directly affect the quality of life and cleanliness of the city. Sanitation crews in November began deploying Clean Streets trucks to pick up abandoned waste after the City Council budgeted $5 million to tidy L.A.’s dirtiest streets.

Since then, sanitation officials said workers have picked up more than 5,700 tons of garbage from trash-strewn alleys and sidewalks. They have also sought to better allocate workers based on neighborhoods’ need.

With ramped-up funding and reorganization, the city’s performance appears to have improved. Since Garcetti took office, 15% of requests went unfulfilled compared with 27% in the previous 2 1/2 years.

But city services still follow the same uneven pattern. Take Van Nuys and Boyle Heights, which had a similar number of requests. Since Garcetti was elected, 30% of requests in the east side area were pending compared with 1% in the Valley neighborhood.

Public Works Board President Kevin James acknowledged the inequities but asserted they result from greater demand for sanitation workers in some areas.

“Ideally you want to spread service out at the same level, but we don’t live in that world — we live in a world where some areas have more significant need than others,” James said.

City officials find it difficult to judge how well workers are cleaning Los Angeles streets. Citing technological glitches that have dogged the sanitation bureau since the rollout last year of new computer software for tracking service requests, officials cautioned that they could not vouch for the accuracy of data collected since last fall.

After The Times alerted the sanitation agency to the large number of pending requests for trash pickup, the bureau paid 20 temporary workers more than $13,000 to randomly visit several thousand sites with requests dating back more than five years. Those visits, conducted in June, found that many locations had been cleaned, but officials say they don’t know whether it was done by their own employees or others — such as nonprofit workers or neighborhood volunteers.

The data-tracking problems come at a crucial juncture for the city agency.

The mayor has ordered the sanitation bureau to build a citywide catalog of street cleanliness conditions by the end of the year. That will require a team of inspectors to survey every street and alley across the city and assign a rating that will be used to prioritize cleanup efforts.

Leo Martinez, who oversees solid resource collection for the sanitation bureau, said he has talked to residents who have complained that their alleyways haven’t been cleaned in years.

The new initiative should help eliminate the massive backlog of dumping requests, he said.

“This mayor wants a clean city,” Martinez said. “What is it going to take to get the city to where everybody feels that we’re living in a good neighborhood, that the services are being spread equally across the board? Because I’m in South L.A. I don’t get these services, but you live in Palisades and you get that.”

The problem of illegally dumped refuse has been aggravated over the years by bureaucratic shuffles and shifting funding priorities.

The Bureau of Street Services was once in charge of cleaning up dumped refuse, but funding for the work was cut off in the summer of 2012. The Bureau of Sanitation has since been responsible for picking up abandoned trash when residents call to alert the city. After alley cleaning lost its regular funding, junk began to pile high across the city.

“In those two or three years, a whole lot was up in the air and no service was being provided for the most part,” said bureau head Enrique Zaldivar.

Even today, with renewed promises to curb illegal dumping, sanitation officials say they still don’t have enough money to do the job. James said earlier this year that it would take at least $25 million annually to keep Los Angeles clean. Garcetti and the City Council gave the bureau a $9-million budget for illegal dumping this year.

Eighteen workers are assigned to respond to the more than 2,000 illegal-dumping complaints that come in every month.

Weary of government inaction, many public and private groups not officially responsible for cleaning the city’s streets — including City Council offices, neighborhood councils, business improvement districts and volunteers — have taken on the problem.

On a June morning, one such group — the East Hollywood Neighborhood Council — turned out to pick up trash on North Kingsley Drive, parallel to the 101 Freeway. The block had racked up a half-dozen requests since last summer — and none had gotten a response from the sanitation bureau, records show.

The piles of dumped trash included bottles of anti-freeze, hubcaps, foam mattresses, bags of potatoes and a discarded sex toy. Ute Lee, 78, who resides at a nearby retirement home, made a face and exclaimed as she smelled feces and urine wafting from a pile of rubbish.

“I’ve lived here for four years,” Lee said. “And it’s always bad like this.”

Hoy: Léa esta historia en español

ALSO IN THE NEWS

Good intention or public nuisance? Cities brace for a resurgence of clothing donation bins

Lead contamination found at up to 10,000 southeast L.A. County homes

How to prepare for a destructive El Niño winter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.