U.S. Army Corps of Engineers says Whittier Narrows Dam is unsafe and could trigger catastrophic flooding

- Share via

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has determined that the 60-year-old Whittier Narrows Dam is structurally unsafe and poses a potentially catastrophic risk to the working-class communities along the San Gabriel River floodplain.

According to an agency report based on research conducted last year, unusually heavy rains could trigger a premature opening of the dam’s massive spillway.

“Under certain conditions, the spillway on the San Gabriel River can release more than 20 times what the downstream channel can safely contain within its levees,” the report said. “Depending on the size of the discharge, flooding could extend from Pico Rivera, immediately downstream of the dam, to Long Beach.”

In addition, engineers have found that the milelong earthen structure could fail if water were to flow over its crest or if seepage eroded the sandy soil underneath.

On Thursday, the agency said it was developing measures to address problems at the dam, which the corps recently reclassified as one of its highest priority safety projects in the nation.

The San Gabriel River plunges 9,900 feet, from boulder-strewn forks in the mountains down to Irwindale. It then meanders in a gravelly channel to lush Whittier Narrows, a natural gap in the hills that form the southern boundary of the San Gabriel Valley. From there, its flows are tamed in a concrete-covered channel for most of its final journey to the Pacific Ocean.

The river and its aquifers serve more than 3 million people in the San Gabriel Valley and southeast Los Angeles County. An estimated 1 million people people live and work along the floodplain.

Los Angeles County and municipal officials are working with the federal government to develop emergency plans that can be implemented if necessary before repairs to the dam are completed.

Greg Fuderer, a spokesman for the corps’ Los Angeles district, said the retrofit operation likely will begin in 2021.

That work is expected to include replacing the existing spillway with a system less likely to malfunction, as well as shoring up the dam’s foundation to reduce erosion and prevent subsidence that could result in floodwaters spilling over the top, officials said.

“In the meantime,” Fuderer said, “we cannot approve any sort of construction projects in the floodplain under our jurisdiction.”

That includes a controversial proposal to build a 14,000-square-foot discovery center in a wildlife sanctuary behind the dam.

“The Army Corps’ position is another nail in the coffin for us,” said Sam Pedroza, an environmental planner for the Sanitation Districts of Los Angeles County and a key member of the center’s stakeholders committee. “After all the years we’ve put into it, we now must decide whether to move forward with a modified project, perhaps someplace else, or nothing at all.”

Advocates see the center as a gateway to an “emerald necklace” of parks and greenways connecting 10 cities along the Rio Hondo and the San Gabriel River. It would be filled, they say, with state-of-the-art interactive exhibits designed to teach visitors about the work of regional water districts, which donated more than $250,000 to the project.

“If it turns out that the discovery center is not going to be built at Whittier Narrows,” Kevin Hunt, general manager of the Central Basin Municipal Water District, said in a statement, “we will ask for our money back.”

Opponents — led by the grass-roots Friends of Whittier Narrows — have decried the size of the proposed center, which would replace a small facility that currently is filled with terrariums and stuffed animals. The new construction would necessitate the removal of dozens of century-old sycamores and eliminate foraging and nesting grounds for raptors and federally endangered birds including California gnatcatchers.

The Gabrielino Band of Mission Indians had denounced plans to build the center on grounds they regard as ancestral lands.

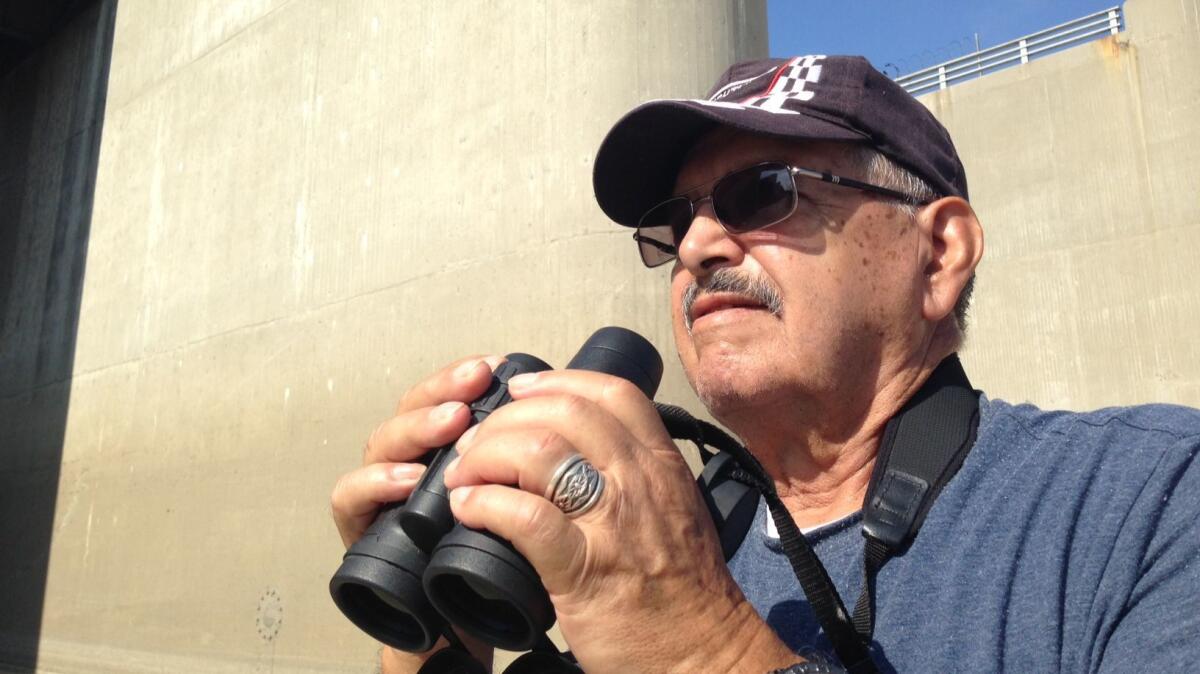

“The discovery center was a giant fiasco from the start, so good riddance,” Eddie Barajas, 80, said on a recent weekday morning as he ambled along a trail edging the base of the dam’s spillway.

As a boy, Barajas said, he hunted doves and rabbits in the area with a beat-up, single-shot .22-caliber rifle. Now an avid bird watcher and neighborhood activist, he has made a priority of protecting habitat in the 1,492-acre sanctuary hemmed in by freeways, warehouses, a high school and fast-food outlets.

Giving the landscape dominated by willows, sycamores and the massive dam an approving nod, he said: “This place looks just like it did in 1952, and we plan to keep it that way.”

Twitter: @LouisSahagun

UPDATES:

5 p.m.: This article was updated throughout, with addition details on the report and the proposed discovery center.

This article originally published at 10:20 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.