It could cost $3 billion to prevent disastrous earthquake damage along San Francisco’s Embarcadero

- Share via

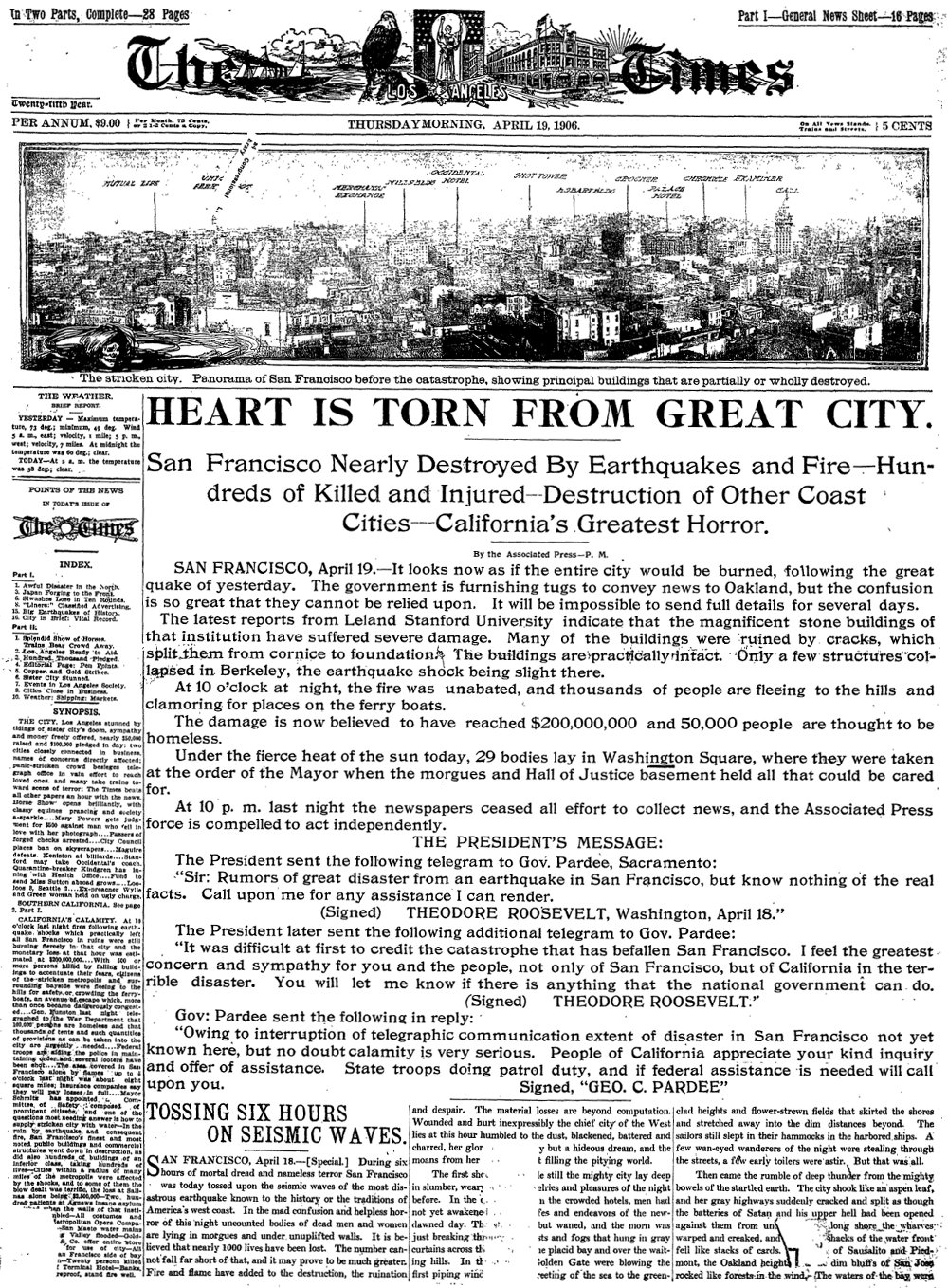

Rising at the tip of Market Street, the Ferry Building here has long been a symbol of survival.

The building withstood the great 1906 earthquake and fire that destroyed much of the city 110 years ago today. It was a gathering point for survivors back then, and again for commuters after the 1989 earthquake brought down a section of the Bay Bridge.

But city officials and engineers now say the popular Embarcadero area surrounding the Ferry Building faces a different kind of seismic threat.

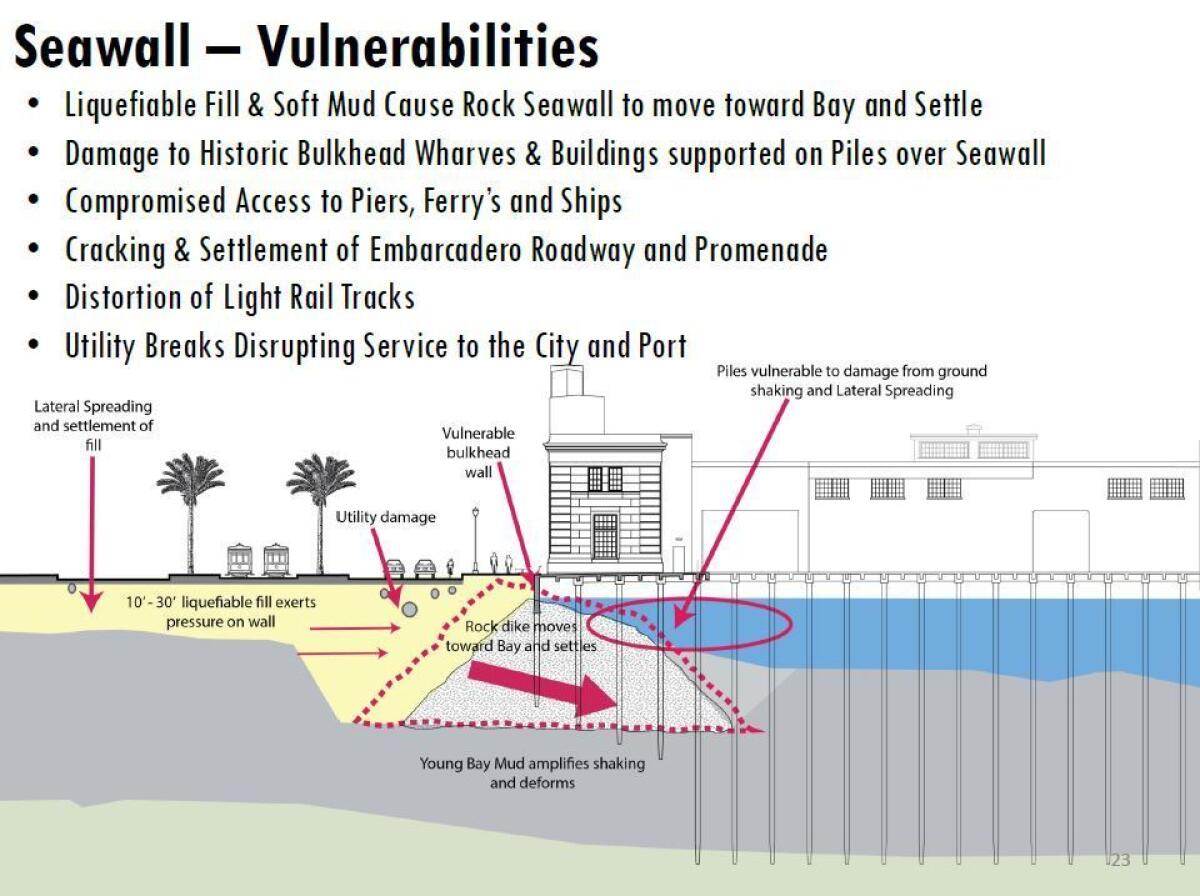

New studies have found that a massive sea wall along the Embarcadero could be shoved toward the bay by more than several feet in a massive earthquake, taking with it some of San Francisco's most famous and expensive real estate.

Look back | 110th anniversary of devastating San Francisco earthquake

Engineers say a picturesque three-mile stretch of the Embarcadero between Fisherman's Wharf and AT&T Park is at risk. This is one of the city's most bustling areas, where historic streetcars glide down the street, sharing the waterside boulevard with tourists, joggers and foodies sampling the various eateries.

A report by the Port of San Francisco released last week outlined a grim scenario if the sea wall gives way: severed access to the ferries; damaged piers, wharves and the buildings on top of them; distorted streetcar tracks; big cracks in the Embarcadero roadway and promenade; and disrupted utilities. A damaged sea wall could also be further eroded by waves and tides.

The cost for securing the wall was placed at roughly $2 billion to $3 billion.

"This is one of the most critical pieces of infrastructure in the city, and most people don't even know it even exists," said Patrick Otellini, San Francisco's chief resilience officer. "We can't be afraid to have the conversation. We have to talk about the risk."

The sea wall vulnerability is particularly frustrating because officials have worked over the years to improve the seismic safety of individual buildings along the Embarcadero.

The Exploratorium, a science museum at Pier 15, was seismically retrofitted in 2013, based on recommendations by structural and geotechnical engineers, said spokeswoman Shannon Eliot.

The Ferry Building was retrofitted in 2003. Officials are optimistic about its survival even if the sea wall lurches because the building sits on a forest of timber piles in deep bay mud that floats, keeping it from shaking too much, said Steven Reel, a professional engineer with the Port of San Francisco. AT&T Park was built around 2000 to modern seismic standards and sits on a new foundation, Reel said.

A big problem is that most of the buildings and piers in San Francisco's northern waterfront were built after the 1906 earthquake and have not been tested in a major temblor, the port report said. The 1989 Loma Prieta quake, which was centered about 60 miles to the south in the Santa Cruz Mountains, was considered only a minor test.

The sea wall was built to expand San Francisco's ancient coastline that once went as far inland as the Transamerica Pyramid near Chinatown, two-fifths of a mile from today's waterfront.

By reclaiming the tidal marsh as land, San Francisco was able to build out over deeper bay waters, constructing port facilities for large ships. To this day, the sea wall provides protection against floods.

The wall was formed by carving a trench in the mud and filling it with a pyramid-shaped dike of rocks that was topped with a wall. Land was created behind the wall using fill, which acts like a liquid when shaken.

The liquefied fill could increase pressure on the sea wall during a major earthquake. Making matters worse, below the wall is a weak mud. That means the sea wall — while not expected to completely fail — could suddenly move toward the bay during an earthquake, damaging the wharves, piers, buildings and roadway above it.

"If there wasn't anything built there, that wouldn't be a problem," Reel said. "But we've got utilities through that zone. We have a beautiful and important promenade that's built in that zone. The Embarcadero corridor is important."

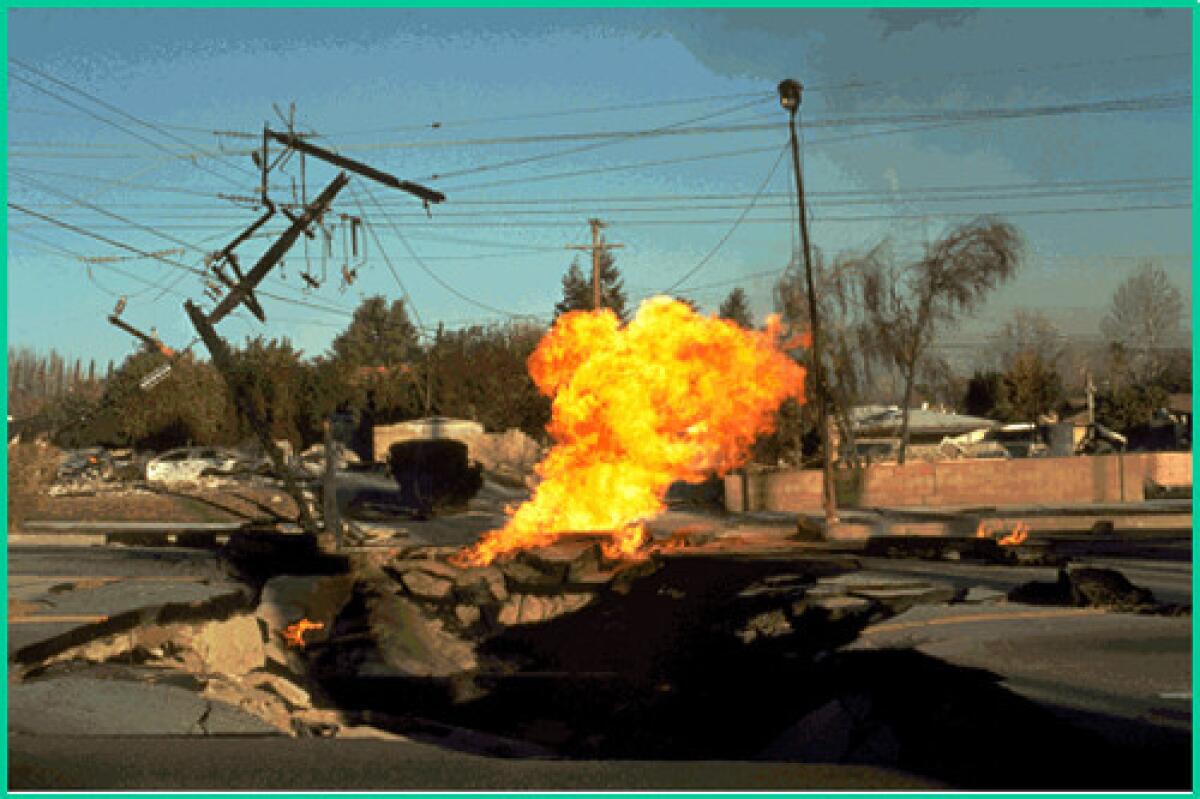

Ground sliding can cause huge problems in an earthquake and make roads impassable; in the 1994 Northridge earthquake, gas mains ruptured and caught fire.

Another problem: Some of the historic wharves — decks that extend the shoreline beyond the sea wall — are supported by brittle concrete columns that could collapse during shaking. That poses a risk to the buildings on top of the wharves and the finger-like piers attached to them.

It was only recently that officials began to be aware of the sea wall's vulnerability.

The first clue came when the port rebuilt a wharf near the Franciscan Crab Restaurant, and geotechnical engineers discovered that there was liquefiable sand underneath the rock wall. A similar problem was found when the port rebuilt a wharf at Brannan Street — a thin layer of bay mud was found under the rock wall there.

"The overall risk: It's greater than we previously thought," Reel said.

At risk is $1.6 billion in property along the Port of San Francisco and disruption of $2.1 billion a year in rent, revenue and wages. The waterfront is a major draw for millions of tourists, who annually bring in about $11 billion.

Scientists and historians say the sea wall is what made today's City by the Bay possible. The city started pushing into the bay in the 1850s — a gradual process that took 70 to 80 years to complete, said historian Joseph Amster.

"It was essential for maritime navigation and created a lot of land in a city that's pretty hilly," said Robin Grossinger, a senior scientist at the San Francisco Estuary Institute. "The bad news is ... we moved the city out toward the bay and we put the city in a more challenging place to protect.

"We made these decisions a hundred years ago, and now we have this unexpectedly expensive result," Grossinger said.

It would be decades later — when a magnitude 7.5 earthquake hit Japan in 1964 — that scientists realized that how land had been reclaimed from bays posed a liquefaction problem, said Keith Knudsen of the U.S. Geological Survey's Earthquake Science Center. "If we were doing that today, it would be done a lot more differently," he said.

Solutions are still being formulated. One idea is to stiffen the mud supporting the rock wall by injecting it with cement — kind of like forcing down bits of fruit into a dish of Jell-O. "You put enough fruit down there, and you've firmed it enough … and you really stabilize the rock," Reel said.

Officials are also suggesting retrofitting or replacing brittle concrete supports that hold up the wharves and wall.

Even if they come up with a plan, officials will still have to find a way to pay for it. San Francisco has embarked on a major campaign to retrofit about 5,000 apartment buildings that are at risk of collapse during a big temblor. That effort took more than a decade of planning and delicate negotiations with property owners and tenants.

On the horizon is another looming problem: rising sea waters prompted by climate change. Dealing with that could cost an additional $2 billion.

"If you were to do nothing, somewhere in between 2070, 2100, the old shoreline is going to be back," Reel said. "And now with sea-level rise, the sea is trying to take that land back."

Twitter: @ronlin

FROM THE ARCHIVES

For San Francisco, a dress becomes a reminder of survival

Ruth Newman dies at 113; oldest San Francisco earthquake survivor

William Del Monte dies at 109; last survivor of San Francisco quake and fire of 1906

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.