Men tell of sexual abuse by scoutmaster decades ago

- Share via

NEWPORT, Pa. — Even after 36 years, Carl Maxwell Jr.’s thoughts leap to the rustic house at the edge of the golf course, and what happened there.

“It is so old, but it is so fresh,” Maxwell said, recalling the many nights that members of Troop 222 spent at the home of their scoutmaster, Rodger L. Beatty.

He remembers the mattresses that covered the floor in the front room, the queasy anticipation that would set in among the five boys after Beatty said good night and went to his room.

DATABASE: Search for names, locations

“I remember the first time for me,” he said. “The lights were turned off and the moon was out, and I could see it shining through a crack in the blinds. Then all of a sudden it got dark and then it got light again, and you could tell someone passed through the light.”

It was Beatty, he said.

“He started at one end of the room and worked his way right down,” Maxwell said.

Mike Kunkel also remembers being sexually abused at Beatty’s place, and had long kept it to himself.

“I have been married for 20-something years and never said a word about this to my wife until tonight,” he said, an hour after a reporter called and asked to stop by to talk about Beatty. “It was a big bomb to drop on her.”

All five boys, ages 13 and 14, came forward in July 1976 to accuse Beatty in detailed written statements to local Scout officials. He was expelled from Scouting, but no one called the police. Beatty abruptly left town.

“It’s like he ceased to exist after that day,” Kunkel said. “Now I’m wondering: Where the hell is he? Is he in jail? Is he dead?”

Beatty, 66, is neither dead nor in jail.

The longtime University of Pittsburgh social worker, educator and AIDS researcher has been in a hospital intensive care unit since Sept. 28, when he suffered a massive stroke. His family asked David Korman, a Pitt colleague and friend of 20 years, to answer questions on his behalf.

“I’m just shocked by this,” Korman said. “His reputation on the campus is truly outstanding.... I think everyone here will be stunned.”

Korman said Beatty is unable to communicate.

“The only person able to answer the allegations is unable to answer,” he said.

Boy Scout files

The accusations that bind the Pennsylvania men’s lives are detailed in the Boy Scouts of America’s confidential files, a blacklist the organization has used for nearly a century to keep suspected molesters out of its ranks.

Beatty’s is among nearly 1,900 such files the Los Angeles Times has reviewed in recent months. Hundred of suspected molesters, many of them respected members of their communities, were never reported to authorities, the records show.

Much of their long-buried history was cast into public view Thursday, when 1,247 of the files, including Beatty’s, were unsealed by order of the Oregon Supreme Court, two years after a jury considered them as evidence in a landmark sex-abuse lawsuit against the Scouts.

The Times first attempted to contact Beatty in early September, more than two weeks before he fell ill. He did not respond to repeated email and phone messages.

The newspaper also sought out the former Scouts he was alleged to have abused. Of the five, two have since died and one could not be reached.

Like many other incidents of alleged abuse described in the files, those involving Beatty played out in a small town, where Scouting was a big part of boys’ lives.

Maxwell, now 50, said Newport was a great place to “swim in the cricks” and fish in the Juniata River, a few blocks down the hill from the small duplex where he and his sister grew up and where he still lives much of the year. It is about 25 miles from the capital, Harrisburg, and many of its 1,500 residents are state employees. His late father, Carl Sr., worked for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation.

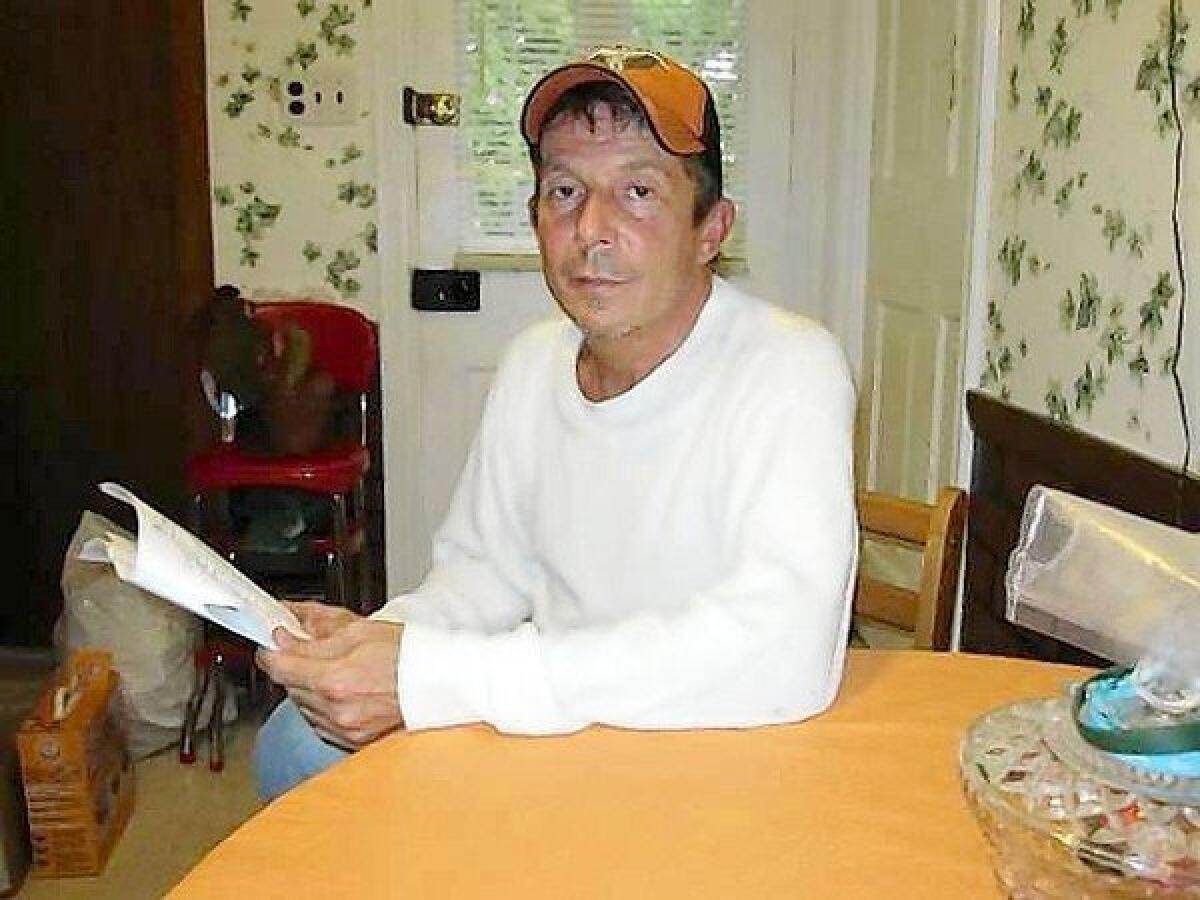

“I wouldn’t have wanted to grow up any other place,” Maxwell said, sitting at the kitchen table. “You know how you hear people say you can leave the doors unlocked? Well, this was that kind of neighborhood.”

Sponsored by a local church, Troop 222 was led for three years in the mid-1970s by Beatty, then a county drug-and-alcohol counselor in his late 20s. He met some of the boys, including Mike Kunkel and his stepbrother, J.P. Culhane, while helping their parents with alcohol abuse or other problems.

“My mom and dad were having problems, and they started seeking therapy through the county,” Kunkel said.

Kunkel said he and Culhane were “loose cannons” at that age and Beatty suggested that they’d benefit from Scouting’s structured environment. So they joined his troop.

Beatty took a special interest in some of the boys, Kunkel said. He’d take them on camping trips and to events such as the Klondike Derby, where Scouts test their skills. They always had plenty to eat and lots of fun.

“He taught us how to drive a car,” Kunkel said. “He drove a stick ... so we drove a stick.”

Beatty eventually began inviting Kunkel, his stepbrother and three other boys, including Maxwell, to group sleepovers at his house “out in the middle of nowhere,” near a quarry.

“That’s where we would stay on a Friday night, say, if we were going to a Klondike Derby or something the next day,” said Kunkel, now 50.

Much of the alleged abuse occurred at the house, but it happened on camp-outs too.

“I woke up and found Rodger in the tent,” one of the boys wrote in his statement. “He already had my pants unbuckled, so I tried to get away and he got my pants down and he had sexual intercourse again.”

In retrospect, Maxwell and Kunkel said, it’s hard to explain why the abuse went on for so long. It probably had to do with being 13 and naive, they said, and with Beatty’s position as their trusted leader.

“I look back at it and say, ‘You’re a victim,’ but back then it was like, hey, he was my scoutmaster,” Kunkel said.

Maxwell said the repeated abuse took its toll. His good grades fell. He spent more and more time alone in his room.

“I started to close down,” he said. “My parents didn’t know what was going on. In fact, there toward the end they were ready to send me to a shrink.... I thought, ‘I need to come clean with my mom and dad here.’ ”

Maxwell said that the boys seldom spoke among themselves about the abuse, but that he and his best friend, now deceased, decided they could not put up with it any longer. All five then decided to come forward, he said, and he told his parents.

“My father wanted to kill him,” Maxwell said.

Local Scout officials sat the boys down, one by one, to write out what happened. Their accounts, which left little to the imagination, were given to the top local Scout official and the Boy Scouts’ national office.

Beatty resigned immediately, citing increasing job demands in a July 1, 1976, letter to Scouting officials. Aware that the five boys had accused Beatty of molesting them repeatedly, Arthur Lesh, the church’s troop representative, wrote back.

“Thank you for the time and effort you have expended for us as Scoutmaster,” he said, noting he accepted the resignation with “extreme regret.”

In his 70s and living in the same town, Lesh said in a recent interview that “a lot of what happened and who it happened to” eludes his memory. But he did recall Beatty and the allegations against him. And he said he believed the boys who made them, in part because “there were so many of them.”

He and others affiliated with the troop were shocked and embarrassed by what happened, Lesh said, and no one considered calling the police.

“Nobody wanted to discuss it publicly,” he said. “Nobody was too proud that it even happened, or was allowed to happen.”

Lesh never heard from Beatty again.

Building a career

Beatty went on to earn a graduate degree in community psychology from Pennsylvania State University and a doctorate in social work from the University of Pittsburgh, according to a 2011 resume and his Pitt biography.

He has worked for more than three decades in public health programs, some geared to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community. He had several jobs with the Pennsylvania Department of Health and since 1998 has been an assistant professor at Pitt, in the Graduate School of Public Health’s Department of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology.

“Dr. Beatty’s research focuses on HIV prevention, particularly as it relates to substance abuse and sexual minorities,” his Pitt bio states.

Beatty’s friends and colleagues say they can’t reconcile the man they know with the serial molester portrayed in the Boy Scouts’ file.

“I have done lots of work with Rodger,” said Michael Shankle, a friend and research associate who has known him for 15 years. “I have never seen anything that would lead me to believe anything that would even come close to that. I am so flabbergasted.”

Shankle described Beatty as “a well loved community activist and leader.” Beatty’s resume lists more than half a dozen honors beginning with the National Jaycees’ “Outstanding Young Man of the Year” in 1981 and ending with the 2009 “Red Ribbon Award” from an AIDS-prevention organization.

Beatty has been on a ventilator, according to recorded updates by his family, and he has opened his eyes and moved his arms, legs, fingers and toes. Since his stroke, scores of people have wished him well on Facebook.

“Rodger, you mean so much to me and to many other people whose lives you have touched,” one wrote. “I am praying for you and thinking a lot of you every day.”

Kunkel, one of the five boys Beatty allegedly abused, has been thinking of him, too.

“My first thought is ... I hope he dies and rots in hell,” Kunkel said.

‘It was vile’

After high school, Kunkel spent eight years in the Marines and then 19 in the Army National Guard, including a tour in Iraq. He married a hometown girl, Shawn, had two daughters now in their late teens and works as a produce merchandiser for an independent grocer.

After he and the others reported Beatty to the Scouts, he never again talked about it with his stepbrother J.P., who died in a traffic accident years later.

“I wasn’t proud of it. In fact, I was embarrassed about it,” Kunkel said. “It was something that happened. It was vile, it was foul, but it was something you don’t talk about. You move on.”

He decided to talk to a reporter, he said, because it might help someone else.

Kunkel said he does not think the experience has had “debilitating effects” on him.

“But in the back of my mind it’s always there that people like that are out there,” he said.

He recalled his reaction when a man thought to be a child molester kept riding past on a bicycle to “eyeball” his young daughters years ago.

“I told him, ‘If you stop in front of my house one more time and look at my kids, I will take you out, ‘“ he said.

In a recent interview, Maxwell’s retelling of an abuse incident was nearly identical to the statement he’d written 36 years ago — and hadn’t seen since. He also had a vivid recollection of Beatty.

“I can still see his face like it was yesterday,” he said.

Like Kunkel, Maxwell rarely talked about what happened once Beatty was gone.

“I wasn’t going to let something like that hold me down,” he said.

After high school he attended photography school in Philadelphia, then moved to New York City and worked as a bartender until about 10 years ago. He is retired now, with a heart condition, and spends part of the year in a camper on the Delaware shore.

He had coped well with his memories, Maxwell said, until the child sex abuse scandal involving a former assistant football coach at Penn State broke last year.

“With this Jerry Sandusky thing, all of it just came flooding back — terribly, actually,” he said.

His own childhood experience affected his ability to trust people, and for that he blames his scoutmaster. Looking back, Beatty “should have been led out in handcuffs,” he said.

“All of us boys — two of them’s dead now — but all of us were scarred, and scarred for life by that. I’m sorry, but that’s not something a 13-year-old boy puts out of his mind,” he said. “And he got away with that.”

DATABASE: Search for names, locations

FULL COVERAGE: Inside the ‘perversion files

Times researchers Maloy Moore and Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.