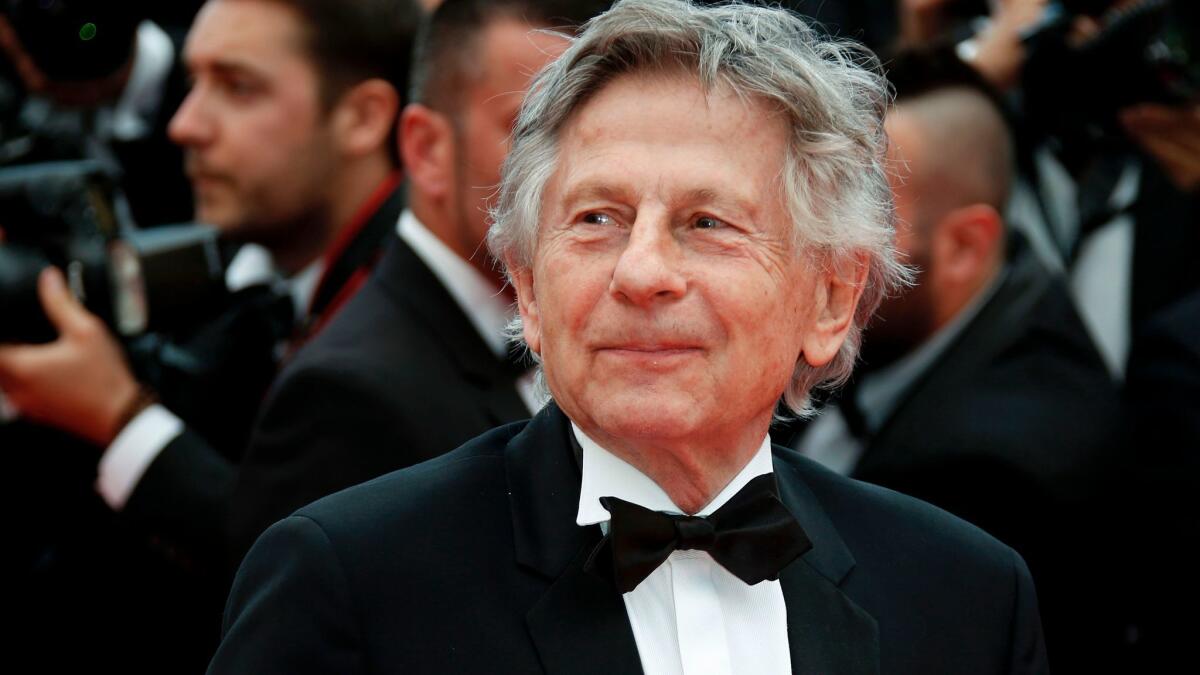

Column: 40 years later, Roman Polanski still doesn’t deserve special treatment

- Share via

In Los Angeles, some old crimes never fade away.

The Black Dahlia slaying.

The Manson murders.

O.J. Simpson.

And Roman Polanski.

“I’m Mr. Polanski’s attorney,” began an email that arrived Monday morning from L.A. super lawyer Harland Braun.

He was writing about an Oct. 29 column I wrote.

In it, I reminded readers that Harvey Weinstein — who made headlines for sexual harassment allegations against him — had been one of the Hollywood cheerleaders who led the brigade in defense of Polanski back in 2009.

Polanski, the Oscar-winning director who fled the United States in 1977 before being sentenced for sexual intercourse with a minor, had just been arrested in Europe and faced possible extradition to the U.S.

So I walked across the street to the L.A. County halls of justice and looked through the Polanski file, and the details were a shock. Polanski had plied his young victim with alcohol and drugs and moved on her physically despite her objections, and when she feared getting pregnant, he had anal sex with her.

She was 13 years old.

“I have never tried to justify or excuse his conduct,” Braun said of Polanski in his first email to me this week. “My purpose has always been to undo what I believe to be judicial dishonesty extending over four decades.”

Forty years after the crime that sent one of Hollywood’s top directors into exile, Braun contends Polanski has already paid the price for his crimes, case closed.

In several emails and conversations, Braun, a big-name attorney who has handled a gaggle of high-profile cases, made several arguments, some of which have been playing out in the courts for years.

First and foremost, he said that in 1977, Judge Laurence Rittenband reneged on a plea deal and sentencing agreement, and that’s why Polanski fled.

Polanski plead guilty to the lesser of the charges against him, statutory rape, because the victim’s family did not want to subject her to the trauma of testifying in a high-profile case. They wanted to get it over with. The moviemaker understood that under an agreement between the judge, prosecutor and defense attorney, he would be sent to prison for a brief diagnostic study and then return to court and be set free.

Polanski was released after 43 days, then heard that the judge was under pressure to deliver a stiffer sentence than what had been agreed to. So he fled the country before his scheduled sentencing date.

Braun argues that the deal worked out by the judge and attorneys was both a promise and a binding agreement.

“The judicial promise is not irrelevant,” Braun argued. “It is the reason he fled and involves the honor and honesty of our system.”

I’m no attorney, but I respectfully disagree.

The deal Braun refers to was not made in open court or on the record. It was cooked up in a private conversation in the judge’s chambers.

That’s the way it was often done back then, Braun argued. Maybe so, but how can the public have any faith in a judicial process that plays out beyond our view?

“Not only is it not binding,” former prosecutor Brentford Ferreira argues, “but a judge can’t make a deal. A deal is between a prosecutor and defense lawyer…. A judge has to ratify a deal, but the judge can always, for good reason, change his mind at sentencing.”

Braun says Polanski has not been prosecuted for unlawful flight “because his flight was lawful,” since Polanski had fulfilled his end of the bargain.

That’s not how I see it. I see a man who committed a heinous crime and skipped town.

“He fled rather than be sentenced,” said Ferreira, adding that a diagnostic study is not a way to serve time, but rather a pre-sentencing tool.

The penalty for statutory rape was shockingly light at the time, Braun said, but that wasn’t Polanski’s fault.

No, it wasn’t. But how much have we really evolved?

The culture of powerful men doing whatever they could get away with has endured for decades, as recent headlines make painfully clear.

Braun said when you add Polanski’s several weeks in diagnostic study with his nine months of house arrest in Switzerland, he has already served what would have been close to maximum time in the 1970s. And he says he has “secret emails” in which court officials acknowledge this.

“Polanski through me has asked the D.A. and the court how much time he owes,” Braun said. “They both refuse to even say. Why not?”

Why should they have to? Polanski created this mess himself when he caught a plane. If anything, he got a great deal while he was here, thanks in part to his celebrity, which discouraged his victim from testifying at a circus trial.

And get this:

Polanski asked for, and was granted, a three-month reprieve before being sent to his diagnostic study, so he could finish working on a movie.

Try to imagine, if you will, an average Joe asking a judge if he can have a three-month grace period before reporting to prison for raping a 13-year-old.

I know the victim has said she wants the case to be dismissed so all this will finally go away, but the best way for that to happen would be for Polanski to stand before a judge and settle the matter, as the L.A. County district attorney’s office insists he do.

Polanski has endured a great deal of tragedy in his life. He survived the Holocaust as a boy but lost his mother, then lost his pregnant wife, who was murdered by the Manson gang. It may well be true that he turned his horror and suffering into art that can be considered a gift to the world.

But what he did to a child was repugnant, and when he thought the price would be an inconvenience if not a career impediment, he ran.

It wouldn’t work as a movie, given the unsatisfying ending and a character I can’t bring myself to root for.

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.