- Share via

aja monet calls herself a surrealist blues poet. When I ask her for a definition, she replies, “A musician of the subversive imagination … a truth-telling magician.” Try as I might, I cannot come up with a more apt description of who she is, what she does and what she means. And if this seems too esoteric, just listen to her debut album, “when the poems do what they do,” and you’ll know exactly what she means.

A word musician of Caribbean descent and American dissent, monet understands poems as life force, expressed and animated through breath, body, memory, experience, imagination, spirits and ancestors. Her poems are powerful and dangerous, like violets pushing through concrete to kiss the sun, or unarmed people, arms locked, chanting and singing, forcing armies to retreat. She is that unstoppable violet beckoned by sun. A warrior who wields words like a bouquet of hand grenades that sprout water lilies upon detonation.

Robin D.G. Kelley and Vinson Cunningham on L.A. solidarity and the Black Radical Tradition.

Wisdom belies her mere 36 years on this earth. She came on the scene at 19, becoming the youngest poet to win the Nuyorican Grand Slam competition. She then tossed aside her laurels and leaped headlong into the raging river of struggle. When we first met in 2016, at a movement retreat in Fruitland, Fla., I knew her as a lead organizer with the Dream Defenders. No one had to tell me she was a poet. Her words, voice, cadence and fiery imagination, blazing like the Florida sun, gave her away. She wasn’t just a movement poet. She brought poetry to movement — to the Community Justice Project, to Say Her Name, to the arts collective she co-founded, Smoke Signals Studio in Miami. And she brought movement to poetry, through live performances and books, including “The Black Unicorn Sings” (2010), “Inner-City Chants and Cyborg Cyphers” (2015), her landmark collection “My Mother Was a Freedom Fighter” (2017) and the much-anticipated “Florida Water: Poems” (2023).

Read, listen and study everything aja monet does. Below is a very brief distillation of a two-hour conversation. We barely scratched the surface. And she’s not done.

Robin D.G. Kelley: Your spectacular collection of poems, “My Mother Was a Freedom Fighter” — the title itself is a kind of universal declaration and yet so personal and intimate. Talk about your mother. Who’s your mother?

aja monet: My mother is probably one of the most fascinating, important people in my life that has shaped so much of how I see the world. After all, she birthed me. She named me.

When I was younger, I didn’t understand all that she was doing. The book, for me, was that expression of: Imagine what the world could have been like for you, what kind of mother you could have been had the world been a little easier on you, had you had the resources and support to be a full human to raise a child and feel supported. I was just thinking about how we take for granted the actual role of mothering as a real struggle.

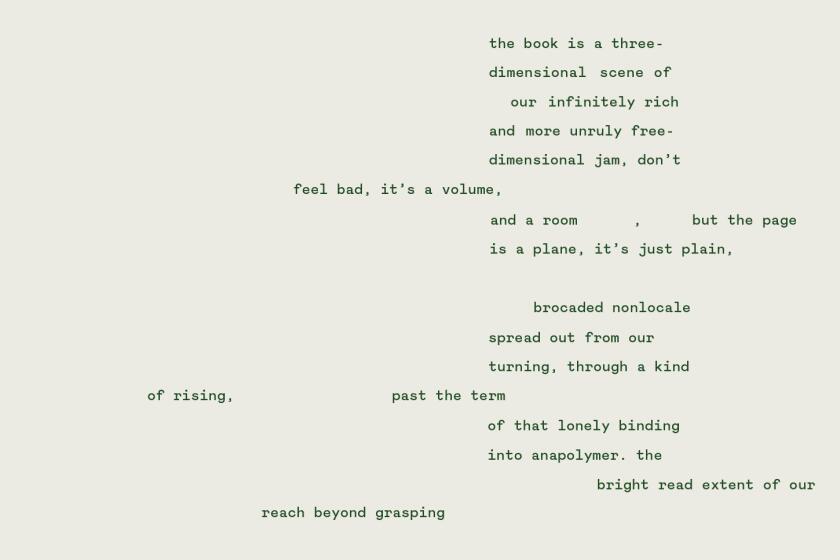

In an excerpt of the poem ‘the red sheaves’ from his forthcoming collection, ‘perennial fashion presence falling,’ the multihyphenate artist gives a sneak peek of an infinitely rich and more unruly freedom jam.

RDGK: Your definition of “freedom fighter” is expansive. In your family’s life, fighting for freedom isn’t the cliché of militants standing up to police dogs and state power. Can you talk about the book’s title and how you imagine what it means to be a freedom fighter as a working-class Black woman in late 20th century Brooklyn?

AM: Everywhere I moved in the world, I saw mothers struggling — to live, to love and to care for the people that they love. We all have to have a mother; somebody created us. Why is it that we have not found a way in our society to, at the very least, create reverence for that in every way, shape or form? It would just seem like a no-brainer.

I think there comes a point in one’s life when you see patterns. You start to ask questions. My grandmother was a big figure in my life. And she was a santera; my grandmother’s Cuban. I grew up with people coming to her to problem solve, to help resolve some sort of conflict or ailment or trouble in their life, including other members of the family. In the summer she would love to sit on the front porch, and she always forced me to sit outside with her — I used to hate it, because I was like, “What am I going to do just sitting here?” And what I realized is that she was teaching me something. We used to sit there, and people would come up and talk to her and I’d overhear all types of conversations, questions and ideas. I learned to read people sitting on the front porch with her. I think that helped me observe mannerisms and patterns and ways of being.

RDGK: So you grew up with the Orishas? When you were coming up as a child, and you saw your grandmother engage in this practice, did you know what was going on?

AM: It’s always been in the periphery of my upbringing, because it was just there. I didn’t have any choice in the matter. Now, it’s become popular and it’s a thing. I grew up in a time [when] you didn’t bring that stuff out in public. You never talked about alternative religious practices outside of Christian, Jewish, Muslim religions. It was real taboo to even bring it up. It never was something that I was necessarily proud of or curious about.

RDGK: Today many contemporary artists draw on ancestor divination for its aesthetics without any deep understanding of the practice or its power. You bring a depth that is really unusual.

AM: It shows up in my work, but it’s just because it naturally does that. It’s not because I’ve been like, “I need to talk about this, and everybody needs to know.” Because, for better or worse, I learned that the power of magic is in its invisibility, it’s silent.

RDGK: You grew up in East New York, in Brooklyn, in the ’90s. Describe that landscape, what it meant for you.

AM: One of the things that I always have to preface with when talking about Brooklyn is that my mother was a single mother who was often trying to find housing and support her kids. So we would live in other places. We lived in Queens a lot of the time that I was growing up. But Brooklyn was the place we often returned to, where I would spend a lot of summers or when my mom couldn’t be with us. I know that people think of east New York as this dangerous, horrible place, but we loved going to Grandma’s house because we got to be outside. We would be on the front porch. We would go out to the park. It was when we didn’t have so many hands over us. We got to be kids, we got to be free. It was the place where I felt like we did have somewhat of a childhood [and] that felt so New York.

RDGK: I read somewhere that you were typing and writing poetry at 8 years old. Walk me through that. How did you come to the form of poetry? What were you reading? What were you trying to express in words?

AM: That typewriter was the first thing I can remember enthusiastically asking my mother for Christmas. It wasn’t for poetry. I just wanted to feel the energy and gesture of being at a typewriter. Because I really loved telling stories. When I was with my cousins, we would make up all these stories; we would pretend.

It was like a musician with their instrument. It’s our official instrument, because the pen and paper are not so fun. Typewriters? You got to put the ink, there’s paper — it’s like a whole dance, a choreography, being with the typewriter. I think the act of that made [me feel] like I’m a real writer — and that was what I was aspiring to. I didn’t really think about poetry until high school.

You cannot beg a god for forgiveness, but you can be ready when he hints at offering it after a long standoff.

RDGK: But you wrote stories.

AM: Poetry in elementary school did come up through Langston Hughes. I remember we went to the Schomburg [Center for Research in Black Culture]. I remember seeing Langston Hughes on the floor, the words on the floor. I remember the simplicity of his poetry.

The only books that I remember having a visceral, really deep impact was “The Diary of Anne Frank” and “Go Ask Alice,” as young-adult books that I was reading. Later on, we started getting the ’hood books with “Coldest Winter Ever” by Sister Souljah, all that.

My introduction to literature and reading was poetry and diaries. There was something about the honesty and being in somebody’s emotions that made me want to have my own diary. That was the first time I was like, “I really, really want to write. I want to have my own little diary.”

RDGK: You emerge not just as a brilliant poet but a brilliant poet in New York — a city that’s full of brilliant poets. I read that you knew Saul Williams way back. When did you meet him?

AM: The first time I met Saul Williams was in the Bay Area after I had competed to join the Brave New Voices youth poetry slam team again, because I didn’t make it in 2004. In 2005 I competed again, and I made it onto the poetry team for New York City. It was the first time I ever traveled by myself somewhere for poetry. I knew I was doing something great — look at us, we’re traveling the world with our poems. My friends make fun of me now, but I was very committed to poetry and the power of poetry and what poetry was going to do to change the world. Saul was the pinnacle of what you could be as a poet at that time, because there weren’t many examples for us.

We went off and won nationals that year, as a team. I say it to this day that if you could have been in those poetry bouts — the things the kids were writing were just so ahead and politically astute. We were talking about Bush, climate and housing — all the issues that now are so popular. At that time, nobody was talking about those things. We take for granted that pop culture had everybody in a coma. No one was really addressing the undercurrent of what was happening politically in the country. It was youth poets and their mentors. We had nothing holding us back. We had nothing to lose. We had no jobs that were going to get taken from us. What could our parents do? It was our little moment to say what we felt about the world that we couldn’t control.

RDGK: That was a real renaissance for poetry, I remember.

AM: I think that there’s a direct correlation to that era of young people, in those communities, to the political organizing moments that we have now. Even the way that hip-hop curriculums were being developed and being used as political education in schools and grassroots community organizations, etc. A lot of those poets who were rappers, who were singers, who were artists, were teaching artists — that’s how they survived. They would take their work into schools and be training up the next generation with the politics of our time through the art and literature that they were sharing. I think that that’s what equips so many young people to have the sort of leftist politics that they do now.

Poet Christopher Soto unpacks how the history of policing has shaped and scarred the urban fabric of Los Angeles.

RDGK: You might be considered, interestingly enough, part of the Trayvon generation — it’s not my term. That is to say, the generation of activists who confronted this wave of spectacular incidents of premature death. And you end up doing so as a grown person under a Black president. Can you tell the story about how you got there, your work with the Dream Defenders, and what it means to be a poet organizer?

AM: For me, I would say we’re from the Sean Bell generation — in terms of one of the moments where a public, outrageous, horrendous tragedy mobilized a lot of young people, or at least awakened me. I’ll never forget the image of the car with the bullet holes in it. Sean Bell was with his wife; it was on their wedding night. He was a young Black brother. The police shot up his car an insane number of times.

There’s been a tense history [with the police] from the time I was a kid, because of my uncles, and what I saw them go through, and my brother, which I have a poem about. Just the way the police addressed us, the way they moved in our community — it’s never been great. If I were to fast-forward to having that be a part of my upbringing, the sort of environment that we exist in, surely it would impact who I would become and the issues or values I would be concerned about. Moving from an emotional place, a truthful place, you feel like something’s not fair. You feel the gravity of injustice, and you want to do something. I think that impacted me, in every way, shape and form. Poetry was the one place where I saw other people who wanted to change something. I don’t think we always felt, at least at that time, that we had organizations to go to.

Fast-forward, my relationship to Florida began because of my relationship to Phil [Phillip Agnew, the co-founder of Dream Defenders], which began because of my relationship to Palestine, which began because of my relationship to poetry ....

RDGK: So you go to Palestine…

AM: January 2015, I go to Palestine, and I fell in love. I fell in love with Phil, but I also fell in love with the movement. I wanted to be a part of people who weren’t just saying they wanted to do something but people who were trying to do the thing. Palestine politicized me in a way that there was no going back the same. I wasn’t going to just go back to trying to be a poet and publish some books.

RDGK: Your forthcoming book, “Florida Water” — are those poems you wrote while you were there? Are they about Florida, about Palestine?

AM: They are a little bit of all of that — they’re notes, journal entries from the time I was organizing. It’s also heartbreak, love, nature — the role that nature played for me in Florida. There are metaphors to Florida water. It all comes back to the childhood of growing up with the Orishas in the background and the ethos of that, because Florida water is one of the main spiritual cleansing waters that we use — the cologne that they get from the store, they use for the spiritual cleanses that my grandmother used to make.

RDGK: Africa is also very important to you, politically, ancestrally, culturally. You spent some time in Ghana recently. Can you talk about that?

AM: I’ve always wanted to go to Africa and never had the ability to go on my own before. [My friend] Vic Mensa, who’s a young poet, MC, artist — [his] dad was from Ghana [and] he ended up going during COVID, building all these relationships, made some music.

During COVID, I had moved to L.A., and I got brought in to do this work with V-Day. I knew that we were trying to build relationships with Black women in the States, but there was still so much for us to mend and so many deeper connections that needed to be made among African women of the diaspora and in the States and African women on the continent. It was an exciting project for me to be brought in to create this new play that would center Black women’s stories but to use that artistic venture to also organize. This organization does work with African women, but it was COVID, so there wasn’t a guarantee that I was going to be able to go. Vic was going and it was just opening back up, so he was my liaison into being able to show me Ghana, because of his family. When I went, I made it a point to connect with women poets and writers and artists. At the time, we were doing this thing called a listening tour — we were trying to just listen to women. The play is called “Voices,” but the most important thing about having a voice and using your voice is also knowing how to listen, and when to use your voice.

RDGK: So the play is a compilation of a wide variety of Black women’s experiences?

Elaine Kahn lives in L.A. and teaches at Poetry Field School. Her poem ‘A WORLD THAT IS NOT REALLY A WORLD’ is part of Image issue 8, “Deserted.”

AM: When they brought me on to do the play, I didn’t want to be the person writing for Black women or speaking for Black women. I wanted it to be an experience where Black women told their stories for themselves, and that it would be a listening experience, that it would be an audio play. I didn’t want it to be a situation where people are trying to act out Black women or overperform. What does it mean for people to really have to listen, to embody the voices rather than for Black women to be further objectified on a stage? I wanted to turn theater on its head because the performative aspect of being Black has so many dimensions. What does it mean to make people close their eyes and listen?

RDGK: This is an audio play comprised of Black women’s stories from around the world, in their own voices. Are you saying that audiences gather to hear the play without any visuals?

AM: No visuals. They have their eyes closed the entire time.

RDGK: Wow.

Let’s talk about the album, “when the poems do what they do.” How did you conceive of this work and what do you want the poems to do?

AM: I have yet to see or witness what the poems are capable of. Because I think that they will always be doing. If they are effective, they will always be doing — and hopefully, necessary. I think about when Amiri [Baraka] talks about a poem being urgent — as urgent as eating bread, or a sweater in the winter. My hope is that the poems will remain necessary and urgent. In terms of this album, I feel so grateful, because as a poet — you see, on [my] wall, all these records that poets have made — I just wanted to be able to continue to live in that tradition and for it to be supported and fully invested in, financially, strategically, production-wise. All of the things that went into making this album took a lot of other people believing that this album was worth making. And it took organizing — it’s probably the culmination of one of the most important organizing projects of my life. Everything led to this moment. So the poems did do — they’ve done and they will continue to do.

I think the poems led me to be taken seriously, as an organizer and as an artist. There was a point in my life when I think the two were at odds with each other or made to feel like they had to be at odds with each other. This album is the first real integration in my creative life, that reflects who I aspire to be, who I hope to be.

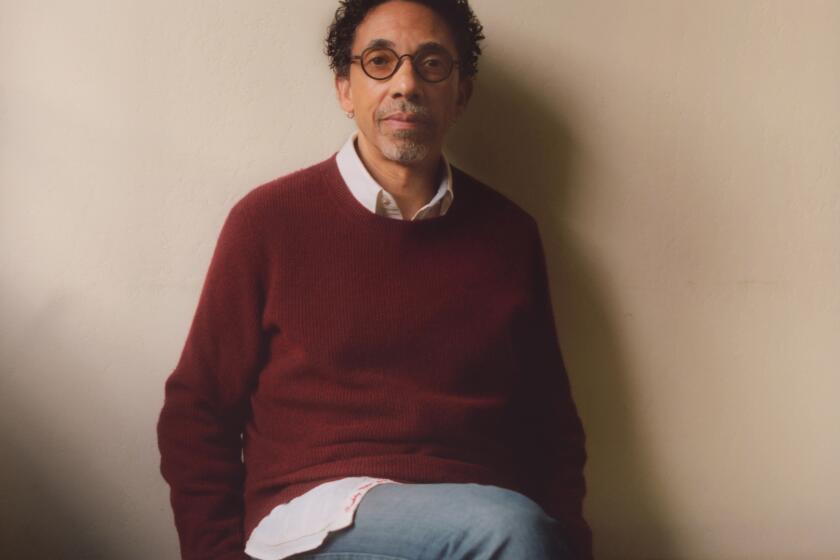

Robin D.G. Kelley is the Gary B. Nash Endowed Chair in U.S. History at UCLA and author of many books, including “Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination.” The new edition includes a foreword by aja monet.