- Share via

This story is part of “Discourse,” a fresh look at the dire state of the bicoastal conversation — free from corniness and cliches. Check out the whole issue — the “New York” issue, if you’re reading between the lines — here.

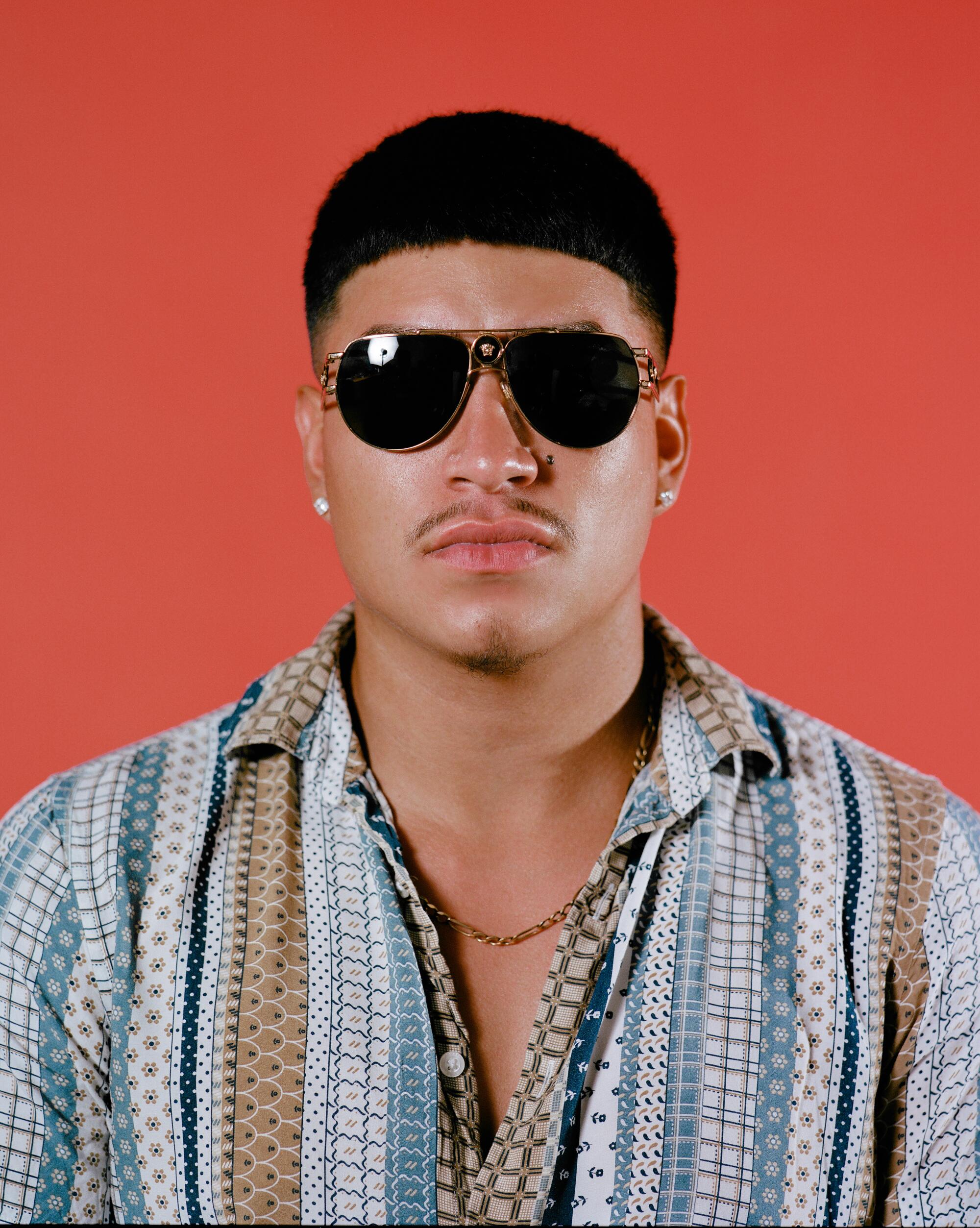

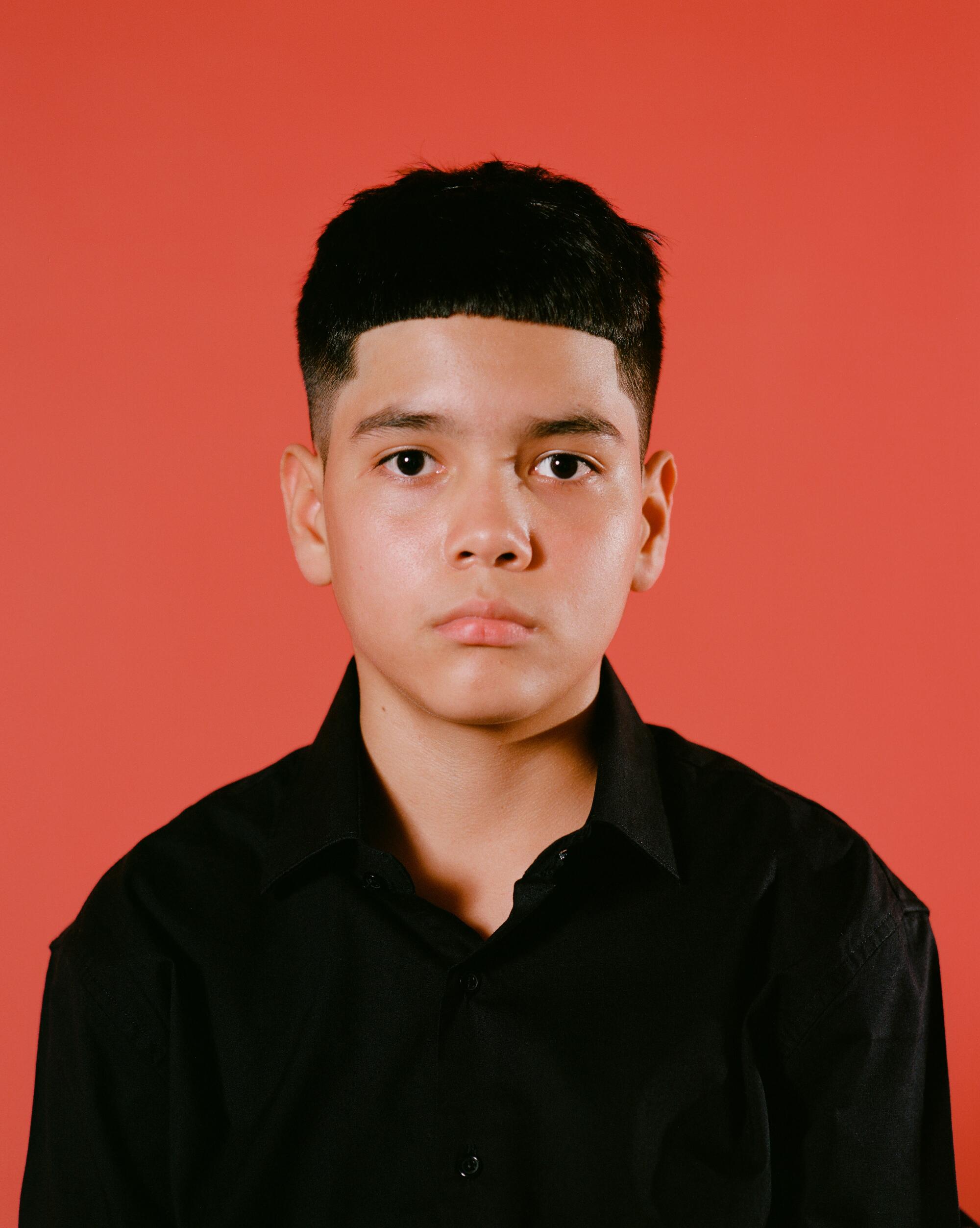

When I text friends to tell them that I’m writing about the Edgar, most reply, “LMFAO.” This doesn’t surprise me. To the unsympathetic eye, the Edgar is a peculiar haircut, so childlike and unflattering as to be offensive. Also known as the takuache, and the cuh, the Edgar can make those who embrace it look like fools or misfits. Moe Howard, the leader of the Three Stooges, wore one. So did Lloyd Christmas, scatterbrained limo driver of “Dumb and Dumber.” The Edgar traveled to outer space with Spock, Captain Kirk’s half-Vulcan confidant, and it sprouts naturally from the head of the Gloster canary, an English songbird. All of this is to say that while the Edgar haircut is far from new, it’s been revitalized in the last couple of years. It’s a massively popular style worn by Latine youth, and one friend, a high school teacher in Long Beach, confirms that at work, she’s swarmed by Edgars. For her, this hair trend is an inescapable part of daily life.

Variations abound but, at its most unadorned, the Edgar is a bowl-shaped cut with a blunt fringe that hangs like a forehead mustache. The hair remains longest on top, and a fade, undercut, or harsh disconnect enhances the style’s potential for voluptuousness. Several Los Angeles barbers that I spoke with explained that the Edgar’s apparent simplicity is an illusion, that pruning a tight and even Edgar requires patience, precision and an obsession with symmetry. These hair professionals validate what those who wear the Edgar, me included, have come to learn. For us, the Edgar is a work of rasquache art, a human topiary requiring habitual maintenance.

Rasquachismo, an aesthetic category that Chicanes began developing nearly a century ago, draws its inspiration from the cheap, the spontaneous, the sentimental, the irreverent, the tasteless and the hardscrabble — all characteristics that apply to the Edgar. Rasquachismo encourages dumpster-diving, reveling in trash, and all things DIY. Scholar Tomás Ybarra-Frausto has theorized this art movement as “a form of resistance” that incorporates “strategies of appropriation, reversal, and inversion.” As a rasquache provocation, the Edgar thumbs its nose at respectability politics. It’s an anti-assimilationist aesthetic choice that reverses and inverts a situation many Latines experienced during childhood.

When I was a kid, my mom, a woman who had never been to beauty school, appointed herself our family barber. She had the power to decide whether my brother, sister and I needed haircuts, and on certain Saturdays she would order us to take turns sitting in the kitchen on a plastic chair. After draping us with homemade newspaper bibs, she told us to stay still. By afternoon, her scissors and clippers had transformed us. The three of us became funny-looking clones, Edgars before there were Edgars. Untold frugal moms helped to craft this hairstyle; they are its authors, and those of us who wear the Edgar today appropriate our own bittersweet memories. As a little girl, I loathed having the Edgar forced on me but never complained about it. Back then, my mom was in charge of my head, not me. These days, the crude, free hairdo that I was made to wear is back, this time because I choose it.

How a cut once deemed déclassé is now at the forefront of chicness.

I first Edgar-ed myself during one of the scariest parts of the COVID-19 pandemic, when salons and barbershops closed their doors and millions of people spiraled into a hair panic. I was working from home and instead of lamenting my inability to have a professional maintain my hair, I realized that I’d been given an opportunity. I could go on an aesthetic adventure and no one was going to stop me. Exercising my mother’s resourcefulness, I sharpened my scissors, oiled my clippers, and crowned myself with an Edgar complemented by a mullet. Barbering myself was therapeutic and I felt triumph. As a child, I’d been punished for cutting my Barbie’s hair and my own. My parents had said that my handiwork made me look like a weirdo. I’d also lusted after a campy toy that they and Santa Claus had denied me: a hairdresser styling kit with a mannequin doll head. Now, I was my own mannequin doll head, free to experiment on myself, and by wearing an Edgar to a family get-together, I proved to my family that little weirdos grow up to be big weirdos.

Texas naysayers who found the Edgar troubling tried outlawing it. At an El Paso high school in 2021, these activists circulated a petition calling for the prohibition of “Edgar Cuts,” alleging that the hairstyle has “detrimental effects” on education, “provokes distraction,” “antagonizes the general student population” and is “a general nuisance.” While it attracts stares everywhere it goes, steps to ban the haircut have yet to be taken in Los Angeles. Here, the Edgar can be seen chasing butterflies through Griffith Park, building sandcastles on Zuma Beach and falling asleep during Mass at Our Lady Queen of Angels. Here, the Edgar continues living its best Mexican American life, and if you listen carefully, you can hear it cheering, “Go, Dodgers!”

Not all of my friends mock the subject of this essay. A blessed few are willing to take the haircut seriously. “There’s an Edgar or two in my neighborhood,” says Luna Lovebad, a Chicana singer who was born and raised in Compton. “I’d see foos wearing it at school and never really paid it any mind until the rise of social media.” Lovebad is alluding to the popular social media account Foos Gone Wild, which has 2.4 million followers on Instagram. According to the website Urban Dictionary, foo is “a slang word commonly used by the Hispanic population to identify a friend or homie,” and there are now so many foos wearing Edgars that FGW developed a theme song for them, its goofy tune the perfect music to accompany stooges having fun. This song came to mind while I was peeking at the FGW IG account shortly before the Fourth of July. On July 2, someone posted a foo-ified portrait of President Biden wearing an Edgar. One follower commented, “AmeriCUH.”

Los Angeles is terrible at housing people. It’s better at warehousing cars. The concrete nautiluses where we temporarily abandon our Kias and Porsches and mopeds produce, reproduce and shelter dualities.

The Edgar belongs to a history of anti-assimilationist hair provocations sported by Mexican American youth. Racists have pointed to these provocations as outward signs of Chicane criminality. For instance, during the 1980s, I recall teachers going to war against one of the slickest homeboys I attended school with, a good-looking kid named José who came to class wearing a fitted white T-shirt, khaki chino pants and corduroy house slippers. Because his look was topped off by a hairnet, teachers acted as if José couldn’t be trusted to sharpen a pencil. Surely, the boy would use it as a shiv. Surely, the hairnet signaled that this cute, little vato was bound for San Quentin. The white gaze has responded to Latina hair similarly. In “Eve’s Hollywood,” essayist Eve Babitz describes a pachuca’s crowning glory, explaining that CC, her Mexican classmate, looks “tough” because of how she stacks her hair. Babitz wonders “if the rumors were true that in the tangle of curls on top, [pachucas] hid wrapped razors for their boyfriends to kill other guys after school.”

It would be unwise to hide weapons in an Edgar though the haircut does conceal a few mysteries. For one, there is no definitive answer as to why the cut is called the Edgar. One theory is that it’s named after Puerto Rican baseball player Edgar Martínez, a legendary hitter who was voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2019. Others say that the Edgar is much older, having originated with the Jumano Nation, an Indigenous civilization whose ancestral homelands included what would become the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Historian Jack Douglas Forbes, a Red Power activist, documented a look that was common throughout the Jumano region during the 1620s, members of various Indigenous communities trimming their hair so that it looked “as if they were wearing caps on their heads.” The Jumano nation vanished from the historical record, seemingly absorbed by the Apache, but the rise of the Edgar does suggest a re-indigenization, a rasquache return to a pre-colonial past.

‘She could count on the strip mall for highly effective magic. She parked in the lot’s only vacant spot, and before walking into the mall’s most brightly lit business, Silly’s Smoke Shop, she got a funny feeling and stopped’

Féi Hernandez, a writer and visual artist born in Chihuahua, Mexico, but currently repping Inglewood, has worn their Edgar proudly. “I like it,” they say. “I feel like it connects me with my inner child because this is the cut I had as a kid.” Friends have clowned on Hernandez because of the cut, blowing up their phone with Edgar memes, some of them unkind, some of them hilarious, and some of them interesting. “I saw that people were coming for it, associating the haircut with chunti-ness,” they muse — “chunti-ness” a reference to all things poor and Mexican. Many of the memes Hernandez received mocked young men into takuachismo, a Latine cowboy subculture characterized by cowboy boots, big trucks and Edgars. Hernandez was especially struck by a meme that juxtaposed a takuache profile with a stereotypically Indigenous one, both male figures wearing the same haircut. Like me, Hernandez also finds the Edgar mysterious. They wonder whether it’s a random trend, like botas picudas, or a sincere attempt at re-indigenization. “The haircut represents Mexicanidad through the rodeo scene. That’s nationalism, not indigeneity, but I don’t think most people are ready to have that conversation.”

Hernandez’s sentimental reasons for adopting the Edgar haircut bring us to camp, that sensibility which Susan Sontag defined as “a tender feeling.” Both Hernandez and I have embraced the Edgar because it returns us to a simpler time, a time when our parents controlled what we looked like. Both of us queer the Edgar, unhitching it from Mexican masculinity and its misogynist impulses, appropriating it so that it takes on a fresher and sassier meaning. On us, the Edgar becomes a queer manifesto, the Edgaria, which states we’re here, we’re queer, and we’re a strange and silly blessing, una bendición silvestre y femenina.

Models: Justin Anaya, Shaid Anaya, Manuel Castano, Anthony Davila, Axel Hernández, Esteban Hipólito, Byron Pulgarin

Myriam Gurba is the author of “Mean,” a ghostly memoir about survivorship that was selected as a New York Times Editors’ Choice. Her next book, “Creep: Accusation and Confessions,” will be released by Avid Reader Press in September.