- Share via

This story is part of Image issue 17, “Offering,” a special gift from L.A.’s creative community to a city that seemingly has it all. Read the whole issue here.

It’s not often — even while working in the arts, which constantly pose difficult questions to viewers, oftentimes questions that have no answers — that we are confronted with the most existential and, in some ways, the most basic questions of them all: questions around fear, death, mortality and love.

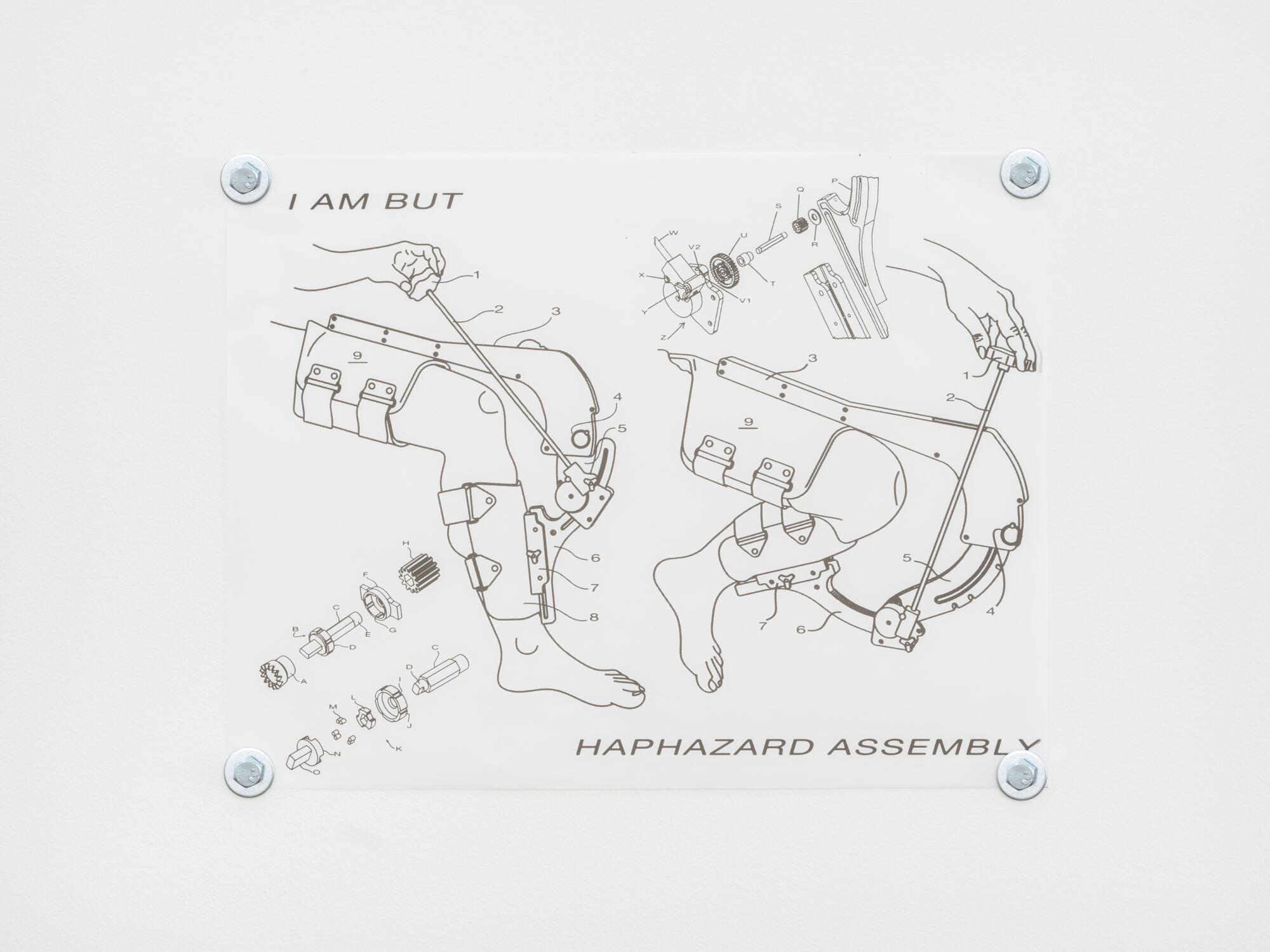

Panteha Abareshi, an artist whose work is rooted in their experience with sickle cell zero beta thalassemia, a genetic blood disorder that causes increasing, debilitating pain and bodily deterioration, is perhaps better equipped than most to guide this discussion. Confronting their own mortality has meant that they have had to deal with both the existential and physical implications of being. What does it mean when our very bodies are strangers to us, estranged from us? Abareshi’s practice abstracts the body, pointing to the failure of representation when embodiment itself fails us. Their refusal to be defined by figuration speaks to the contradiction that our bodies are the only things that we have, yet they are not us.

Our conversation lasted well over three hours, touching on everything from the challenges of representation with identity politics so often at the forefront of an artist’s framing, to unpacking how horror movies (body horror, in particular) embody our societal fears and what they say about the underlying angst and anxiety around our own fragility. But, as the artist reminds us, life’s finitude is precisely what makes it meaningful — making it a little bit easier to acknowledge, and even accept, the precariousness in all of our lives.

Caroline Ellen Liou: What does “offering,” the theme of this issue, mean to you?

Panteha Abareshi: The first time I came across the term “offering” was in a church context, passing the offering plate around. In an offering, even if you acknowledge that there might be a depletion from the person that’s giving, it should always be effortless on the part of the person that’s taking. But we never think about offering as a two-way labor where it’s both difficult to give and difficult to take.

With the artist, there’s an expectation that it’s like a well that never runs dry. It’s like, because you chose this vocation, you chose this practice, you are now obligated to offer and offer and offer. Especially with work that predicates itself on the vulnerability on the artist’s part, on exposing one’s personal experience, there is an inherent expectation from the viewer, from the institution, from all of these consumers that you are constantly going to be generative. You are constantly going to be generous. You are constantly going to be giving an offering. [We need to readjust] how we think about consumption where it’s not easy to give and it’s not easy to take.

I see [this] a lot with work about the Black and brown experience or the immigrant experience, where people want to look at the artwork and still feel good. They want to be engaging with representation but still feel OK being a privileged body. They want to feel like they’ve done the good work by looking at the artwork but still walk away from it and be able to enjoy their day.

We are taught as consumers of art and as consumers in general — just living in the West and being capitalists — that consumption always begets pleasure. That you should always be seeking pleasure as you consume. That it should be comfortable. And that art should be a beautiful, pleasurable thing. The idea of going to look at art is never synonymous with being in distress or being uncomfortable at all. There is sort of an unspoken expectation on the part of the viewer that when you go up to an art piece, that piece should give you everything that you need to have a satisfying exchange with it. That’s why people get so frustrated when something is not just confusing but is refusing to give them what they want, to meet their gaze, to be beheld.

CEL: It seems like an important part of your practice to counter the viewer and push back — there is this element of refusal that is very deliberate.

PA: I’m making work that reminds people of the body that they’re in and the power dynamic that they’re engaging in. It’s uncomfortable for everyone. But discomfort is a really important part of my practice; that is how radical conversation happens. For me, discomfort is not something to shy away from but to lean into, because the disabled body — as a symbol or even as a metaphor — is such a source of universal discomfort.

I push myself to constantly be critical of the relationship that exists between the viewer and the disabled subject and this idea that disability is a never-ending performance. There are so many layers to performance within a disabled art practice, because the disabled individual is constantly having to perform disabled legibility. Even when the disabled body declares itself to be a performer and the performance ends and they step off that proverbial stage, there is a performance that they can never stop doing.

CEL: Can you talk about how refusal manifests in terms of your own body? I’m thinking about how the body is no longer defined by your own embodiment in your 2022 series “THIS IS NOT A BODY.”

PA: In my work, I’m exercising a very specific type of control over my body in the use of it as object and material — “abjectifying” my own body and tearing it away from any sort of corporeal definition, refusing to allow my body to even be identified as a body and taking away the validity of it. In “THIS IS NOT A BODY,” I intentionally excluded my own form and representation. Even though there is a lot of body representation using literal body parts, I was trying to evoke anatomy in so many abstract and sculptural ways, completely disallowing myself even as object, even as material, to appear in the work.

Again, I’m constantly pushing myself to maintain a level of discomfort in my work and pushing myself to be uncomfortable. There’s a constant relearning of my own body because of my illness and my disability, and so it was important that I didn’t allow myself to sit comfortably with what my body can do or could do or can represent in the work because the artist’s body, it functions really symbolically — especially at intersections between being of color and being disabled and being queer.

CEL: Where you become the representation.

PA: Exactly. It becomes a really easy place to rest on. To pull that out as something that I could use or rely on or even just take a moment to catch my breath on is a way for me to push myself to really articulate what I’m trying to say and to de-privilege my own body.

You know, growing up in an able-bodied society, you’re told that bodily autonomy is 100% yours and that you should always feel in control of your body. And so, feeling very confused about not being in control of my body and feeling like I was being controlled by my illness and by my disability — there was such a fear around acknowledging that there is a lack of control even with the thing that you live in and exist in every day. Even if not now, inevitably with aging, we’re all gonna lose control of this horse-drawn carriage at some point.

CEL: Right — to me, the fear of losing control is the same as the fear of mortality, where if you don’t have control over your life, your identity, yourself, then there’s no definition and it’s all just chaos.

PA: We are just a collection of cells. It’s like this bundle of chaos. I find a great comfort in that, and I think that that’s because I am having to contend with malfunction and inability every day. It’s comforting to me to think about the body as chaotic. But I understand how terrifying that can also be if you’ve been taught to expect a certain amount of control and stability and cohesiveness within your body your whole life. We want to feel like we’re so securely strapped into this roller-coaster ride. But really, we barely have a string tied around our waist — we could fly out at any moment. With me and the body that I’m living in, it seems like my perceived proximity to death is perceived as a lot closer, but we’re all there.

CEL: Can I ask what you think happens when you die?

PA: I think you die and that’s it — once your brain functioning stops, life ends there. Even when I was young, the idea of an afterlife or there not being a full stop to life was always scary to me because I was like, why? You’re telling me I have to live forever? That’s awful. I take a great comfort in knowing that things will end. My life has to be finite in order for me to even fathom how to bring meaning into it.

CEL: That’s interesting given that one of the draws of being an artist is the promise of immortality. Do you think about leaving a trace of yourself in terms of your legacy?

PA: If I could have it my way, my art would just disappear when I die. What is most important to me is contributing to these critical conversations that I am trying to be and am a part of. If you are actually, truly contributing to those conversations, your name and your legacy shouldn’t matter because you’ve done what you could to participate in that critical discussion, for them to be expanded and made more accessible. Once I’m dead, I won’t be able to do those things anymore, so it doesn’t matter really.

CEL: If you’re not afraid of death, what are you afraid of?

PA: I’m constantly dealing with the fear of losing control in the ways my life are most important to me. I’m not afraid of dying, but it’s really difficult for me to contend with real-time loss of physical ability and loss of independence. Now, I can’t be independent and self-sufficient because of how my illness has deteriorated. So I’ve had to acknowledge in myself an inability, in very literal ways. And that is really terrifying. It’s really terrifying to take stock of where I am compared to where I used to be and the ability that I used to have and to also look into the future where I’ll be even more disabled than I am now.

It’s also really scary for me to think about alienating my loved ones because of my illness, or the fact that my suffering is something that I can’t keep as an insular experience. I’ve never wanted my illness to make someone else’s life difficult because it makes my own life so difficult. I don’t feel like anyone else should have to suffer because of this thing. But the truth is that when you love someone who is sick and/or disabled, there is an immense difficulty in just living with that — not in any bad way, but to take care of someone is profoundly difficult in a literal, physical sense.

But it’s so scary to me that I would have no control over the effect that I’m having on the people that I love. I’ve isolated myself for many years because of that. I’ve closed people out of my life with the justification that I’m doing it for their good, even if they don’t acknowledge it that way. The people that I have now in my life are the people who have been like, “I’m not gonna let you make that decision for me.” And that has been also profoundly difficult — loving someone and hurting them, and not being able to have one without the other in my life and having to acknowledge that is really scary.

CEL: What strikes me is that all of your fears are not only totally valid but they come from a place of immense caring and empathy. It’s not about your mortality — it’s about how you’re affecting others around you. It sounds like you have some amazing people in your life.

PA: My circumstance, the body that I’ve lived in, has in many ways forced me to be very selective about who I lead into my life, but it’s also allowed me to learn about the type of people that I want to surround myself with. I’m satisfied with all of that. I feel very, very lucky. I’m striving to find people who are willing to see you and know you and to treat relationships as something that require work and constant cultivation. Loving someone doesn’t have to be easy. You should wake up every day and choose to love someone. And you choose to do the work to love that person.

In an excerpt of the poem ‘the red sheaves’ from his forthcoming collection, ‘perennial fashion presence falling,’ the multihyphenate artist gives a sneak peek of an infinitely rich and more unruly freedom jam.

CEL: I think of what we were talking about before, about being able to be human without necessarily being defined by your body. How your body isn’t what makes you human. I think of our relationships as what makes us human. And how, in some ways, we only exist in relation to other people.

PA: That’s a beautiful way of putting it. For a long time, I was really insecure — [dealing] with the need to be desirable — and had a lot of experiences that validated that insecurity. But I’ve also met people that think about their interactions with people and think about love in a way that is not rooted in the corporeal at all. That isn’t something that is reserved for disabled people to experience — everyone deserves to be seen. Being seen is looking at you as a person, not just the shell around the pistachio or whatever.

I feel like we are spoon-fed preexisting definitions of these terms and that we’re doing ourselves a disservice by ascribing to them. If we held ourselves to those definitions of love and relationships — even platonic love [or] queer platonic love — we are still restricting ourselves so heavily. We’re taught to love in such specific ways and that love should give you these very specific things in your life. It is still a taboo to step outside of those definitions and set those demarcations for yourself.

The emotions that we feel when we feel the most seen or understood or connected, they exist in their most personally valuable, furtive, radical states when they are allowed to expand into the unknowable, into the undefinable, into the abstract where you can acknowledge and understand and feel something while also letting it be completely unreachable and uncontainable.

Caroline Ellen Liou currently works as a curatorial assistant at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (ICA LA). She received her BFA in painting at the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, and her masters in contemporary Chinese art and geopolitics at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London.