- Share via

This story is part of Image issue 13, “Image Makers,” a celebration of the L.A. luminaries redefining the narrative possibilities of fashion. Read the whole issue here.

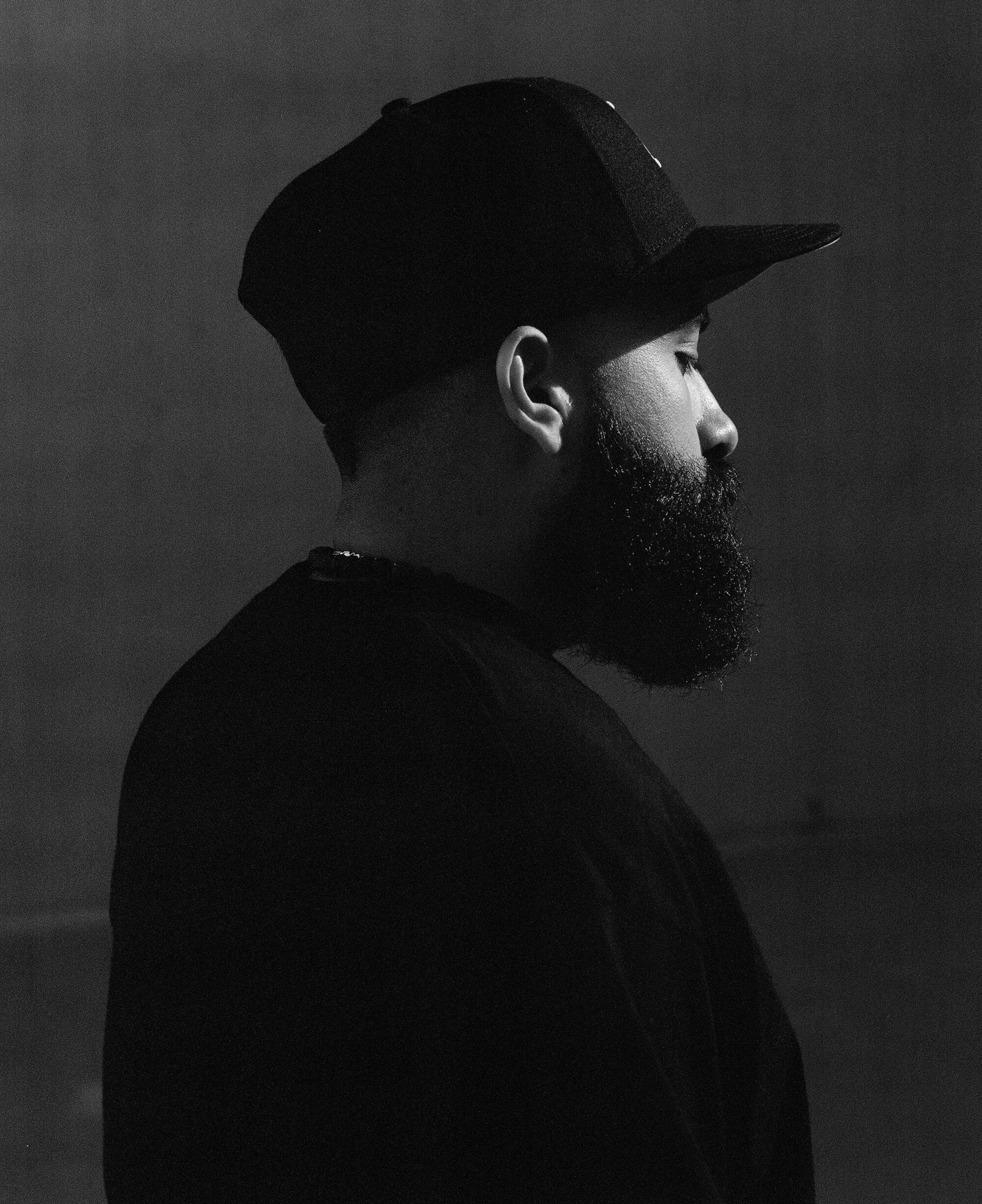

For Çedouze founder Guillermo Juarez, wearing and designing clothes has been about finding a sense of wholeness. For starters, there’s the name of his label. “Çe” stands for “creative expression,” while “douze” refers to the number 12, which Juarez describes as “a number of completeness.” There’s also the circular shape of the grommets included in his designs, which are symbols of fullness and “holiness.”

Juarez started designing pieces in 2015 as a hobby, exploring how he could create clothes that were “more of an art piece that you can wear” rather than an everyday item.

“God is where I receive all my ideas from,” he says. When he sits down to make a design, he looks to a higher being to give him ideas.

In 2015, he began posting pictures of his clothing designs on Instagram. While he didn’t initially intend to use the platform to become a full-blown designer, he was surprised by the amount of likes his photos received. It felt like an “affirmation from the universe.”

“Once I started experimenting with clothing, expressing my creative self through clothing, it just felt like home to me,” says Juarez. “It just felt like this is what I should be doing.”

Born in Guadalajara, Juarez moved to Los Angeles when he was 6 years old. He grew up in an immigrant family; his parents created their own opportunities in a new country, and motivated him to do the same.

The skater and model didn’t need the industry to show her what was cool. She figured it out by getting right within.

As a child in South Gate, Juarez homed in on his Chicano roots. He loved hip-hop and baggy clothes, oldies and lowriders. He made drawings, wrote poetry and made beats to express himself — but these mediums didn’t capture his need for expression as fully as designing has.

Çedouze, he says, is about “opening more doors and opportunities for all our people of color whose voices haven’t yet been heard enough.”

Latinx style and lowrider culture weren’t always embraced. In 2019, Juarez started brainstorming his next collection, specifically focusing on grommets as part of the look. He says a year later, he started to notice a shift: Lowrider and Chicano culture were being regarded “more as art.”

“Before, it wasn’t really noticed as much as it is today,” says Juarez. This year, baggy clothes have been tapped as high fashion — a recent Vogue article called out baggy clothing as an official summer trend, and a Zoe Report article offered advice on “styling baggy clothes for an effortless look.” Elements of fashion normally used to stereotype and criticize Black and brown communities seem to quickly be embraced when they appear on runways or TikTok influencer videos.

But Juarez’s designs are rooted in a sense of place. The “over-exaggerated look” has a lot to do with the fashion, history and music of Los Angeles, which the designer names as his “biggest foundation.”

“There’s no other city like L.A.,” says Juarez. “L.A. is the place, the home, of [this idea that] you can be who you want to be, you can do what you want to do without anyone telling you otherwise. The freedom that L.A. has, especially with the artistic community … I wanted to use that as an inspiration.”

Juarez currently works out of his home studio, a garage that he transformed during the pandemic. He painted all the walls white, for photographs, and embraced the idea of finding a creative routine at home, during a time when many of us stayed indoors. His home sits just about half an hour from the Fashion District, so he can easily gather materials from the area when he needs them.

“That’s my lab. That’s where I usually just get down to creating — from the idea, to the execution, to the photography,” says Juarez. “That’s also where I work on all my pieces. My little garage studio square is where every single piece is given birth.”

Once Juarez finishes designing a piece — like a long black work shirt with a front zipper, or a white, long-sleeve T-shirt, both with the label’s distinctive grommets — he reaches out to friends and models on Instagram who fit his vision. Model Cecilia Alvarez Blackwell, however, took the initiative. As someone also interested in big, oversized fashion pieces and lowrider culture, Blackwell cold-emailed Juarez in April, unsure whether she’d ever hear back. Shortly thereafter, she arrived at his studio to do a fitting and, later, a photo shoot with him.

“When I was with Guillermo and we were working together, I was very pleasantly surprised that we could get to know each other,” says Blackwell. “He made it very clear, a million times, that we were gonna work together — it didn’t feel like he was doing me a favor. A lot of times people act pretentious, and that’s not what Guillermo conveyed at all.”

In the black-and-white images, Blackwell sports a cropped white tank and large hoop earrings that echo the shapes of the grommets in the baggy pants she wears. Her hair is slicked back and her brows and lips are bold. In the final photo of an Instagram carousel, Blackwell sits topless, looking straight at the camera. Every fold along the pants she wears is crisp and striking, the light and shadow emphasizing the drama of the clothing.

A recent series of color photos posted on Instagram shows model José Hernandez outside wearing high-waist, baggy jeans, paired with a white tank with a grommet in the middle. He wears large hoop earrings and sports a thick mustache, a purposeful mix of historically male and female signifiers. In her own modeling experience, Blackwell says she noticed that with Çedouze designs, “You’re able to explore things outside of gender.”

“I like to incorporate that feminine and masculine balance. I’ve learned that when we are in balance, we are whole,” says Juarez. “We are complete. … My pieces are not made for just male or female. They’re made for everyone.”

Eva Recinos is an arts and culture journalist and nonfiction writer born and raised in Los Angeles. She runs a free newsletter for creatives called Notes From Eva.

Lettering design by Vivi Naranjo/For The Times; typeface: Goliagolia

More stories from Image