50 unforgettable trips from Susan Spano

I arrived at the hotel first, checked in and walked up the road to see about exploring the river by kayak. The man in the rental office near the landing said it would take about an hour to float down the Semois from Chiny to Lacuisine, where heâd pick me up in a truck. So I clambered into a bright yellow plastic kayak and set off, hoping I wouldnât encounter any Class IV rapids.

As it turns out, the Semois is about as savage as the

>> Read more (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

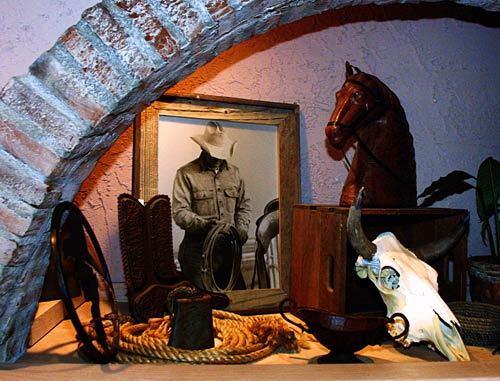

About 100 miles north of the Grapevine, near the turnoff for Coalinga, straw-colored hills bubble up and Harris Ranch appears, an oasis at Exit 334, where the sprinklers always seem to be turned on, watering neatly trimmed lime trees and beds of flowers. Often, a man selling bonsai plants out of his truck is stationed across from the entrance.

Like most exits on Interstate 5, 334 has a handful of the kind of chain restaurants and motels that always remind me of a road trip I once took with a friend. When we stopped at a Dennyâs, she called the restaurant the symbol of everything wrong with America. I like their tuna melts but must admit I know what she means, which is partly why I love the independently owned Harris Ranch Inn & Restaurant. To me itâs the symbol of whatâs right with America.

>> Read more

Pictured: Harris Ranch restaurant (Gary Kazanjian / For The Times)

The Hotel del Coronado hovered in my mind as I drove south from L.A. Iâd never stayed there but knew about it from the 1959 Billy Wilder movie âSome Like It Hot,â which was filmed partly at the hotel. Storied, elegant, traditional, the Del opened on Coronado Island (actually a 5.3-square-mile peninsula west of downtown San Diego) in 1888 and is one of a handful of grandes dames in the West such as the Fairmont Empress in Victoria, Canada, and the Ahwahnee Hotel in Yosemite National Park.

>> Read more (Christopher Reynolds / Los Angeles Times)

I had driven California 14 before to Death Valley, loving the way the roads along the way head off forever on straight shots through the desert. Just when youâre about to get bored, 14 plows through Red Rock Canyon about 150 miles northeast of L.A., with its tilted cliff faces striated like Neapolitan ice cream. As the Sierra comes into view to the west, 14 yields to 395 and you enter the Owens Valley, in the hot, dry rain shadow of the mountains.

>> Read more (Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

At the entrance to Palm Springs, where California Highway 111 turns into Palm Canyon Drive, the smashingly restored Tramway Gas Station symbolizes the resurgence of the town and the style, re-christened as mid-century modern. The gas station was designed with a soaring âbutterflyâ roof in 1965 by Albert Frey, a Swiss-born architect who worked with Le Corbusier in Europe before moving here in the 1930s to become one of the townâs defining architects. Boarded up and threatened with demolition three years ago, the gas station was brought back to life by two San Franciscans who have turned it into a gallery specializing in objets dâart for the garden.

>> Read more

Pictured: Tramway Gas Station (Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

I let the car tell me what to do, and it turned off on Route G18 at Bradley, which leads eventually to the Nacimiento-Fergusson Road. I bought corn chips and a packaged tuna sandwich at a gas station along the way and picnicked beside blowzy yellow roses in the still garden at the Mission San Antonio, founded in 1771 by Father Junipero Serra. Mozart seemed right for the Nacimiento-Fergusson Road, which posed no challenge even to a wimpy driver like me. At the roadâs crest, intersected by the Cone Peak Trail, I did something Iâd long been meaning to do: I took the top down, so that descending the mounded ridge brushed with purple lupine and goldenrod, I could feel the Pacific wind messing up my hair.

>> Read more

Pictured: Bixby Historic Bridge (Ricardo DeAratanha / Los Angeles Times)

Knowing I was a foreigner, my neighborhood greengrocer consistently overcharged me at first. Now she throws extra apples and tomatoes in my bag. I will miss these people and my handful of dear French and American expatriate friends. I will miss having my sister come to visit me in my ideal little Left Bank apartment. I will miss my hairdresser, Frank, on the Rue du Pre aux Clercs, and the flower peddler on the Rue du Bac whose breath always smelled of alcohol. I will miss Monoprix, the Arlequin movie theater on the Rue des Rennes -- especially on Sunday mornings -- and the winter and summer sales at shops along the Boulevard St.-Germain.

>> Read more (Ian Langsdon / EPA)

The Louvre has been standing alongside the Seine of Paris for more than 800 years, first as a medieval fortress built around 1190 by crusading king Philippe Auguste (Philip II) and then as a rambling royal palace on which a long chain of French artists and architects put their marks. The kings of France were insatiable collectors, so when the palace opened as a museum in 1793, the treasure-trove became the property of the French people.

>> Read more (Remy de la Mauviniere / Associated Press)

Advertisement

Stand at the pedestrian walkway on the graceful Art Deco double-decker drawbridge that carries

>> Read more (Jeff Haynes / AFP / Getty Images)

Near the village of Loenen we saw our first thatch-roofed windmill and crossed over a one-lane drawbridge. (The attendant told us he worked from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. in summer but had to be summoned by telephone when someone wanted to go over the bridge in winter.)

Between the villages, we traveled through polder land mowed by goats, sheep and cows, which left me craving a cold glass of chocolate milk. Every farmhouse we passed looked like something out of a painting by Pieter de Hooch or Jan Vermeer, with windows kept so scrupulously clean that they gleamed like diamonds, revealing glimpses of thriving potted plants, lace antimacassars and china caddies inside.

>> Read more

Pictured: Amsterdam (Gail Fisher / Los Angeles Times)

Italians say that Naples is real, edgy and unvarnished in the way that tourist-choked Rome and Florence are not. At almost every turn, Naples made me think of the old courtesan Madame Hortense in âZorba the Greek,â at once so charming and so pathetic that she constricts the heart.

>> Read more (Ciro Fusco / EPA)

Of the glorious, never-to-be-forgotten

>> Read more

Pictured: Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul (Dmitry Lovetsky / Associated Press)

Advertisement

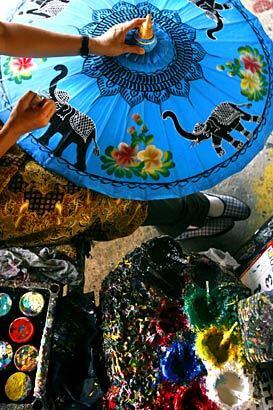

Generally, in the evening, I dined up-market, though even at Baan Suan, a stunning northern Thai compound, the most expensive dish on the menu was $7. Baan Suan, about 10 miles north of town, specializes in northern Thai cuisine, including frog legs cooked in basil. Noisy croaking on the riverbanks suggested that the meat was quite local.

Darkness fell as I tucked into a plate of soft-shell crab and another of curried chicken in coconut sauce. A man rowed a boat across the river, then lighted a chain of lanterns, visual poetry to go with dinner.

>> Read more (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)