Noir splendor

- Share via

“I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on $4 million.”

The mansion Philip Marlowe is about to enter at the beginning of Raymond Chandler’s classic 1939 Los Angeles mystery novel, “The Big Sleep,” holds many secrets, both real and fictional.

Marlowe — played by Humphrey Bogart in the film noir version — finds inside its massive doors a dark world fueled by jealousy, blackmail and murder. It is proof that money does not buy happiness — but it can buy an incredible hilltop manse.

Chandler’s model for the palatial home, according to mystery buffs, was the Greystone Mansion that has loomed castle-like over Beverly Hills since 1928, when it was built by the oil-rich Doheny family on a 12-acre lot carved out of a 400-acre ranch. Its cost at the time: $4 million. Inflation would boost the figure to about $43 million today, but the actual amount to replicate a structure of such grandeur would probably be far greater, making it a contender for the most expensive residential estate in Southern California.

The Aaron Spelling mansion in Holmby Hills, completed in 1988, is larger — 56,000 square feet compared with Greystone’s 46,000 — and the cost reportedly was $48 million. But what would make Greystone almost unthinkable as a construction project today are the materials used, including 3-foot-thick walls of Indiana limestone and a roof of Vermont slate.

“Just the cost of bringing in those materials would be incredible,” said architectural historian and author Charles Lockwood, who in 1984 prepared a history of the house for the city of Beverly Hills, current owner of Greystone. “Everything was the best money could buy.”

Money can’t buy atmosphere, but Greystone has it as much as any noir creation. It would be hard to find a home more steeped in the Los Angeles lore that embodies both the sun-drenched promise of a bountiful life as well as its dark underside of mystery and scandal.

Greystone has been unoccupied for more than 20 years, but by no means has it been abandoned. Millions around the world have seen its interiors and exteriors without knowing it, because Greystone is one of Hollywood’s most popular residential film locations.

Steve Martin danced with Lily Tomlin in the great hall, the witches of Eastwick concocted brews in the kitchen and the Green Goblin plotted against arch-nemesis Spider-Man on the marbled landing.

Greystone has always been much more than a dwelling: It is a brooding declaration of power and privilege.

Edward Doheny struck oil in a mostly hand-dug well near the current Belmont High School in Los Angeles in 1893, the same year his son Ned was born. The discovery was a springboard that took the Dohenys from dire poverty — they were at the time living in a downtown boarding house and were several months behind on the rent — to presiding over a financial empire that made them one of the most wealthy and influential families in the country. Greystone was built for Ned and his family.

“Of all the lavish gifts Edward Doheny gave his beloved son, the 55-room baronial castle was, by far, the most extraordinary, considered to be the most luxurious private residence south of William Randolph Hearst’s spectacular estate at San Simeon,” wrote Margaret Leslie Davis in her Doheny family biography, “Dark Side of Fortune.”

After waging a competition between two of the top Los Angeles residential architects — Gordon B. Kaufmann and Wallace Neff — Edward Doheny chose the London-born Kaufmann, who later would become world-famous for his designs of Hoover Dam, Santa Anita racetrack and the Los Angeles Times building. But for Greystone, the look was to be largely English Tudor.

“Spanish Revival was the trend here,” said Lockwood, “but they were looking eastward toward the look of old money. They wanted something out of Main Line Philadelphia or the north shore of Chicago.”

The house took almost two years to build, along with other features that included a 16,000-square-foot stable, 10-car garage (equipped with mechanic’s lift), two-bedroom gatehouse, domed greenhouse, terraced gardens, lavish fountains, cypress-lined pathways, artificial waterfall and vast lawns.

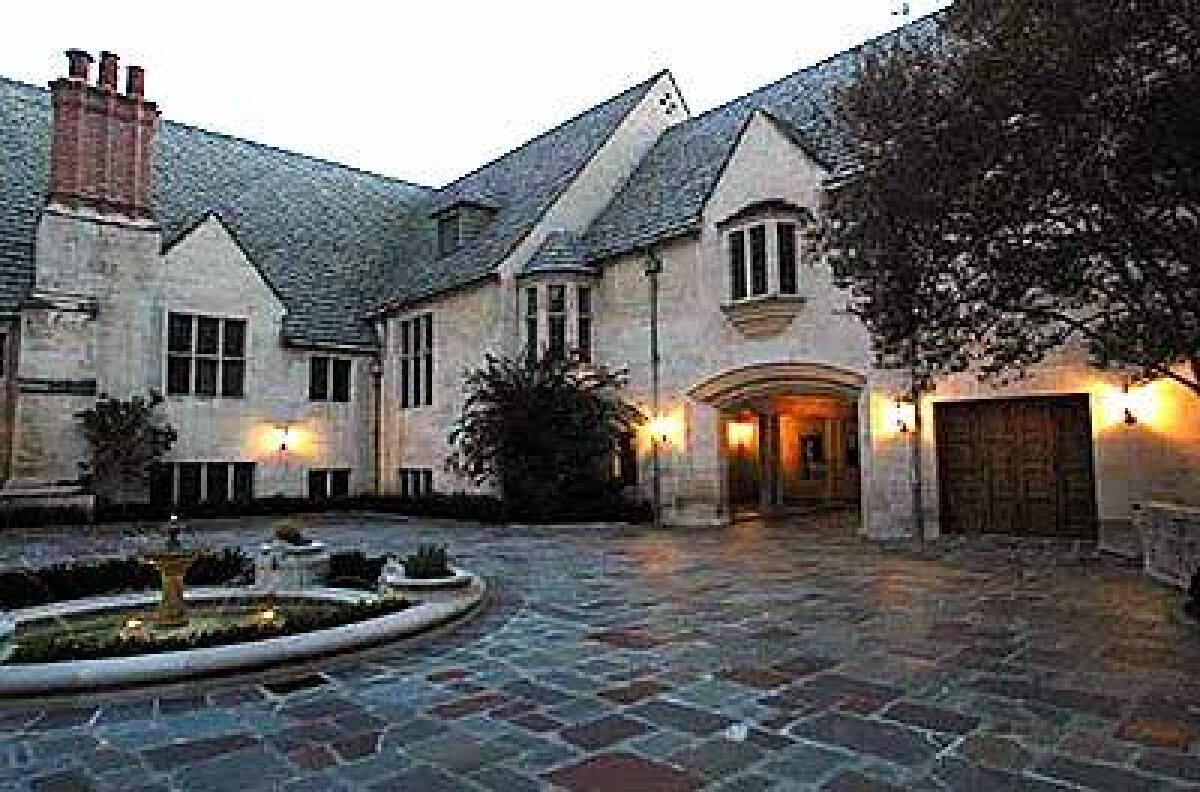

Reached at the end of a long, winding driveway, the arrival court was entered through an arched porte-cochere. The slate-paved courtyard, where the city occasionally holds chamber concerts and other events, provides a good vantage point to take in the exterior of the main house, with its thick limestone walls, leaded-glass windows and slate roof (so heavy that it’s supported by an unseen concrete slab).

The mansion was designed to be a secure fortress, with high walls, iron gates, round-the-clock watchmen and rooftop spotlights aimed at the two nearest police stations to signal trouble.

Which came in abundance on the night of Feb. 16, 1929.

“Right here was where the body was found,” said Beverly Hills’ director of recreation and parks, Stephen Miller, stepping into a disheveled first-floor room that once was a guest bedroom. Ned Doheny, 35-year-old heir to the family fortune, had been shot through the head. Nearby was the body of his trusted secretary, Hugh Plunkett, also dead of a bullet wound. After a quick investigation, authorities ruled that a deranged Plunkett shot his employer and then turned the gun on himself, but to this day the sensational crime is a source of rumor and speculation.

It was classic film noir, a term derived from roman noir, used by French literary critics to describe British Gothic novels. The American screen version of noir — which reached the height of its popularity in the 1940s and 1950s — was just as moody as the British print version, but employed snappy dialogue to go along with the disillusionment.

In “The Big Sleep,” Bogie questions a reluctant Eddie Mars.

Mars: “Is that any of your business?”

Marlowe: “I could make it my business.”

Mars: “And I could make your business mine.”

Marlowe: “You wouldn’t like it. The pay’s too small.”

Raymond Chandler, whose series of Marlowe novels began with “The Big Sleep,” was an oil executive before taking up writing, and there is a good chance he visited Greystone in all its glory, said Elizabeth Ward and Alain Silver in their book-length photographic guide to “Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles.” There are several descriptive passages in “The Big Sleep” that suggest he patterned his fictional mansion — occupied by the oil-rich Sternwood family — after the real thing.

“The room was too big, the ceiling was too high, the doors were too tall, and the white carpet that went from wall to wall looked like a fresh fall of snow at Lake Arrowhead,” he wrote.

On Nov. 8 and 9, parts of Greystone will again be open to visitors, who can determine for themselves how similar the two are. Members of the American Society of Interior Designers will be using several rooms to showcase their designs. In addition, the estate grounds, now a public park, will be the site of a city flower and garden festival.

Although much of Greystone’s majesty is intact, the structure has suffered over the years. Fireplaces have been ripped from walls, light fixtures have been replaced by cheap knockoffs and wood floors were left to deteriorate. The city hopes to restore it to its former resplendence so that it can be used as a conference center and for a variety of events, including weddings. But this house, designed in a futile attempt to keep the evils of the world outside its walls, could perhaps never feel settled. No one understood that better than Chandler.

“The white made the ivory look dirty and the ivory made the white look bled out,” he wrote. “The windows stared towards the darkening foothills. It was going to rain soon.”

Just inside the main entrance is perhaps the most imposing interior view — down a wide, black marble staircase and onto a landing made of black and white marble tiles laid out like a giant checkerboard. The thick wood banisters on either side of the stairs, which also branch upward to a second-story landing, are carved in an elaborate, stylized grapevine motif. According to Miller, they were carved by artisans on-site.

The high-ceilinged living room, with its musicians gallery above, probably was where most of the public entertaining was done. It’s now unadorned except for a very busy-looking white fireplace that looks convincingly solid. But rap on it and it sounds hollow. “It’s a fake, put in some movie at one point,” Miller said. The real living room fireplace — one of seven originally in the house — was found in pieces in the basement.

Most of the rooms downstairs can be reached through a series of interior doors. “You didn’t have to go out into the hallways to go from room to room,” said Jill Collins, president of the Beverly Hills Historical Society. “Who knows what was going on behind those doors?” She lightly pushed a section of wood paneling in the living room and it sprang open to reveal hidden shelves. “These were probably for liquor,” she said. A whole section of wall in the billiard room — located in the recreational wing that also contains the screening room and bowling alley — slides upward to reveal a full bar so complete it had its own bathroom.

Upstairs were the main bedroom suites. Ned and his wife, Lucy, each had separate bedrooms, dressing rooms and bathrooms, plus a common sitting area. Several of the upstairs bathrooms have scales built in. Step on a pressure plate in the floor and a round wall dial springs to life, showing your weight (the one in Ned’s bathroom still works). In keeping with the consistency of the design, there is a dial in Lucy’s bathroom but it does not have hands and there is no pressure plate.

“She was a lady,” Collins said.

Ned, his wife and five children had been in Greystone only three months before the murder. The police detective first on the scene later wrote a book in which he questioned the findings of the investigation. He pointed out discrepancies and mysterious circumstances.

Over the years, amateur sleuths have suggested that Ned was the shooter in both deaths or that a third person was involved. The death of his son left Edward Doheny broken in spirit, according to several accounts. He died in 1935. Lucy remarried and lived on in the house. In 1954, she sold the bulk of the family ranch property to Paul Trousdale, who developed it as Trousdale Estates. Greystone was sold to a Chicago-based developer, and Lucy left for a smaller but still lavish home known as the Knoll estate. She died in 1993 at age 100. Knoll now is owned by billionaire Marvin Davis.

At the end of the film of “The Big Sleep,” Bogie finds love with the elder Sternwood daughter (played by his true-life love, Lauren Bacall). A dash of sentimentality and hope for the future was also often a feature of film noir.

But the book did not surrender to a happy ending. Marlowe found himself back where he began — outside the door of the mansion, alone.“The bright gardens had a haunted look, as though small wild eyes were watching me from behind the bushes.” He drove back down the hill toward the city, stopping for a couple of double Scotches that “didn’t do me any good.”

“What did it matter where you lay once you were dead? In a dirty sump or in a marble tower on top of a high hill?”

What did it matter how rich you were, how much oil you discovered, how big your house? In the end, “You were dead,” wrote Chandler. “You were sleeping the big sleep.”

For information on the Flower and Garden Festival at Historic Greystone Estate, call (310) 550-4753. Tickets are $25 for adults, $12 for children ages 11 to 17, free for children 10 and younger.