- Share via

On a blistering hot Friday in August, Donald Winston, 56, lugged black trash bags stuffed with belongings up four flights of stairs to what had just become his first-ever home of his own.

Winston sweated profusely as the plastic bags began to shred on the hard floor, but he beamed once they were all hauled, pushed or kicked into the studio apartment. Air conditioning graciously blasted cool air. The unit near downtown Los Angeles was outfitted with a bed, small table and a microwave. Most important, it offered what Winston called “breathing room.”

The day before, Winston had been living about 20 minutes south of the apartment complex, in a shelter for homeless men and women who were formerly incarcerated. Most of the residents live with mental illness and almost all use drugs, which the shelter allows so long as the drugs are used offsite, according to the shelter administrator. Winston shared a room with 32-year-old Jacob Lopez. The two became friends, but it was tight quarters.

“Waking up in your own place — that’s crazy,” Winston said over the phone the day after his move.

Winston’s journey to housing hinged in part on his health insurance.

At the beginning of the year, California began rolling out extensive reforms to Medi-Cal, the state and federally funded healthcare program which serves low-income adults and children. The reform initiative is known as California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal, or CalAIM.

The idea is to create a system over the next five years that goes beyond traditional medical care to cover other aspects of people’s lives, including some housing and food needs.

Lack of housing and inadequate food are major contributors to health problems. Taking care of those parts of life — social determinants of health, as experts refer to them — could not only improve the lives of Medi-Cal clients, but also save the program money over time, advocates say.

“Housing is health. Food is health. These things are already a part of the health system,” said Kelly Bruno-Nelson, executive director of Medi-Cal/CalAIM for CalOptima, a publicly funded healthcare system in Orange County. The circumstances in which people live can account for nearly half of the differences in health outcomes from one county to another in the U.S. while clinical care accounts for only about one-fifth, according to research cited in a recent federal health policy report.

If CalAIM works as planned, it would reduce health disparities by helping some of the state’s most vulnerable groups, including homeless individuals struggling with serious mental illness or physical needs.

Getting to that point will not be easy, however, not least because of the difficulty of dealing with Medi-Cal, a Byzantine system that requires significant upfront costs and expertise to maneuver.

Health plans that frequently deal with Medi-Cal devote extensive resources to billing and eligibility requirements. But many of the nonprofit groups that provide services to the homeless aren’t set up to do that. Advocates fear that the newly available help won’t get to those in need if it’s too hard for providers to jump through all the hoops.

A trio of organizations interested in supporting Medi-Cal beneficiaries offered grants in January to 20 nonprofits which serve the homeless to see if they would benefit by billing Medi-Cal for services that are now reimbursable under the reforms. Only 10 accepted, with another joining later, according to Brittney Daniel, health program officer for nonprofit California Community Foundation, one of the funding organizations. Just four of the nonprofits have moved forward in the process to become Medi-Cal providers.

“A lot of homeless service organizations are operating, kind of always in the red — overworked, underpaid, very stressful work environment,” Daniel said, adding that workforce shortages are rampant. Some, particularly smaller ones, see making the operational changes necessary to work with Medi-Cal as daunting or simply beyond their budget.

“Even the sheer paperwork” of becoming eligible to be a Medi-Cal provider “is a hurdle,” said Erin Jackson-Ward, director of the Community Benefit Giving Office at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, another one of the organizations funding the nonprofits.

Jennifer Kent, former director of the California Department of Health Care Services, which designed the CalAIM reforms, said while she strongly supports the program, she’s concerned about what she sees as an overly aggressive timeline for implementing it.

Overpromising and under-delivering “makes the department look bad or incompetent,” said Kent, who is now a consultant.

“This is where I’m acutely worried about how hard you make people work under what kind of unreasonable expectations,” Kent said, “because you burn people out too many times, and all you’re left doing is beating dead horses.”

Winston is among the first batch of clients to benefit from a new CalAIM program, known as Community Supports. He connected to the Los Angeles Christian Health Centers in December, just as it was about to start offering services to help people find and keep housing through a Medi-Cal contract.

Previously, the clinic usually stepped in to help only after a homeless patient had a path to housing lined up. Now, it can help people “from scratch” until they’re handed the keys, said Taylor Nichols, director of social services for the Health Center.

That has “really allowed us to be able to provide the intense support and accompaniment that we need to, to help people get housed, because it’s such a process,” Nichols said.

About 110 people are enrolled in the health center’s housing navigation program, up from roughly 80 in late July.

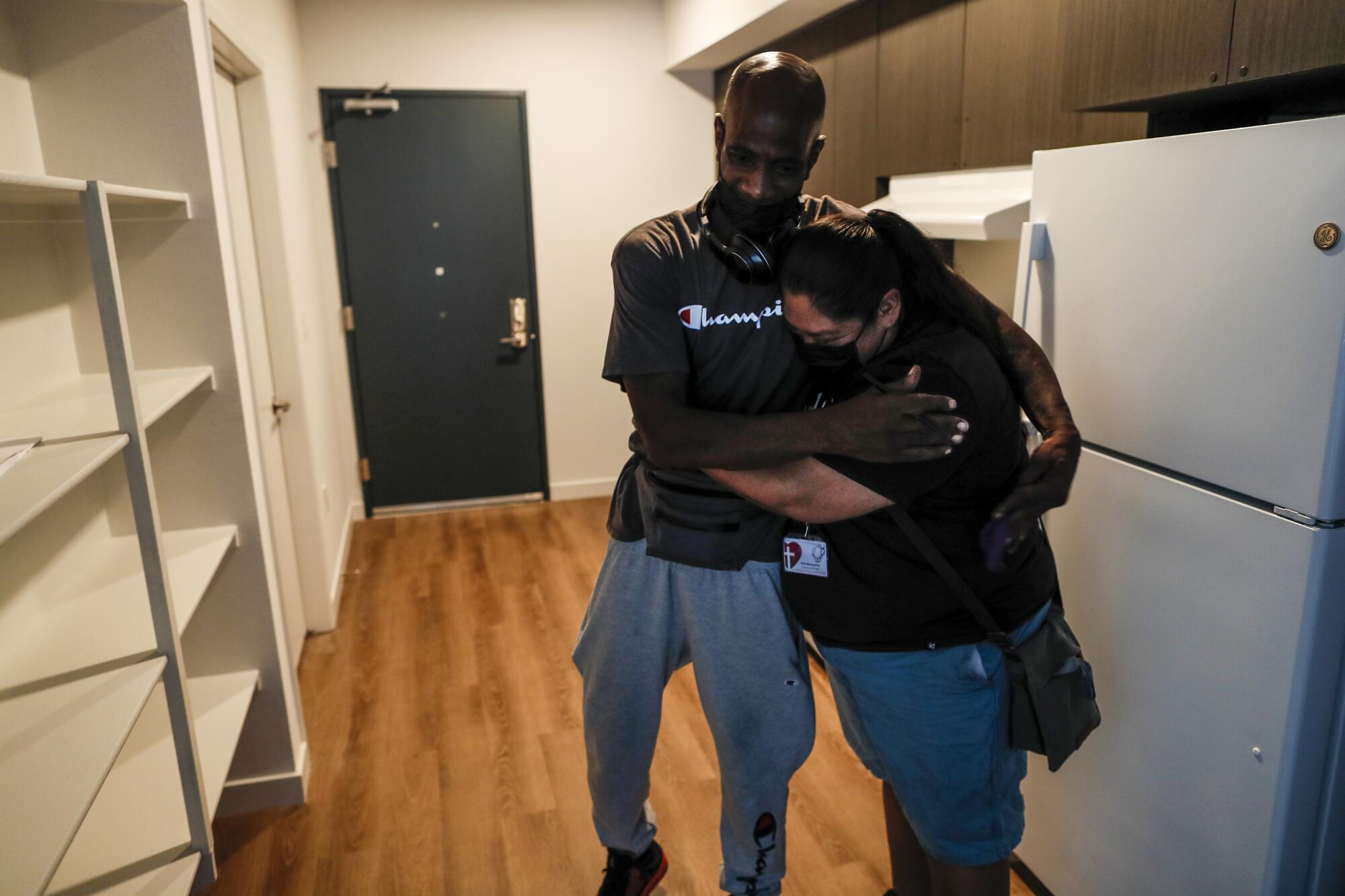

Winston said he hit it off right away with his housing navigator, Tanisha Harris. The two met at Joshua House, the center’s large medical facility in Skid Row, and they began meeting weekly. As he grew comfortable, he opened up to her, sharing his difficult past and leaning on her during his “darkest days.”

A Los Angeles native, Winston said he grew up in and out of juvenile hall, which he said was preferable to severe abuse he suffered at home.

His first arrest came at age 8, according to a report compiled by the shelter where he recently stayed. At around 13, he said he nearly shot himself — his first brush with suicidal ideation — after a troubling conversation with his mother. In 1986, while at a youth correctional facility in Ontario, he said he passed an exam to graduate from high school.

Winston’s mother and sister were homeless when he got out of juvie, and he said he began breaking into warehouses to get by. “Hustling” helped put them in homes, he said, but it landed him behind bars multiple times. He estimates he’s been to prison roughly 13 times as an adult. His most recent stint ended in the summer of 2020, when he was released from state prison in Delano.

In March of last year, Winston said his nephew accused him of stealing $31,000. According to Winston, the nephew — who he has was living with — pulled a gun on him. Winston said he had nothing to do with the robbery, but left, landing at a shelter.

Winston said he’s been diagnosed with bipolar and schizophrenia disorders and takes psychiatric medication to treat symptoms, including hearing voices. Suicidal thoughts continue to haunt him, belying his outward sunny demeanor.

Harris, the housing navigator, helped Winston get a voucher for permanent supportive housing, which provides money to help cover rent payments and access to services like physical and mental healthcare. In March, he was matched to his apartment.

The large complex, completed in January, houses roughly 100 people — 75% are veterans and the rest are Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health clients, according to Carlton Carter, the intensive case manager for all of the residents.

The match didn’t lead to an immediate move, however. Winston had to hunt down identification and income documents, complete an application, wait for the apartment to undergo repairs and updates — and for the Los Angeles housing authority to approve the application and unit, Nichols said.

As the process dragged on, from weeks into months, Winston became discouraged. To get him through the tough times, he sometimes played conversations with Harris in his head. Poetry helps him channel feelings when there’s no one to talk to. Then, suddenly, good news came: All they needed was a better photo of his California I.D. and he was in.

Harris was by his side as he signed his lease papers in a spacious recreation room in the Hartford Villa Apartments.

“OK, you’re on your own,” property manager Jeff Fogel told Winston as he handed him the keys.

Winston and Harris laughed and cracked jokes as they walked up to the unit.

“Don’t be acting crazy,” Harris joked, “because I’d hate to come back.”

This article is part of the Mental Health Parity Collaborative, a collaborative effort involving the Los Angeles Times, the Carter Center, the Center for Public Integrity and other newsrooms across the U.S. aimed at covering challenges and solutions to accessing mental health care.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.