Landmark houses: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House

When The Times’ Home section convened a panel of historians, architects and preservationists in 2008 to vote on the region’s best houses off all time, the Ennis House ranked No. 3, ahead of the modernist Eames House, the John Lautner spaceship-on-a-hill known as Chemosphere and the Arts & Crafts beauty of the Gamble House. (Only Rudolph Schindler’s Kings Road House in West Hollywood and Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House in Palm Springs finished higher in the voting.) (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

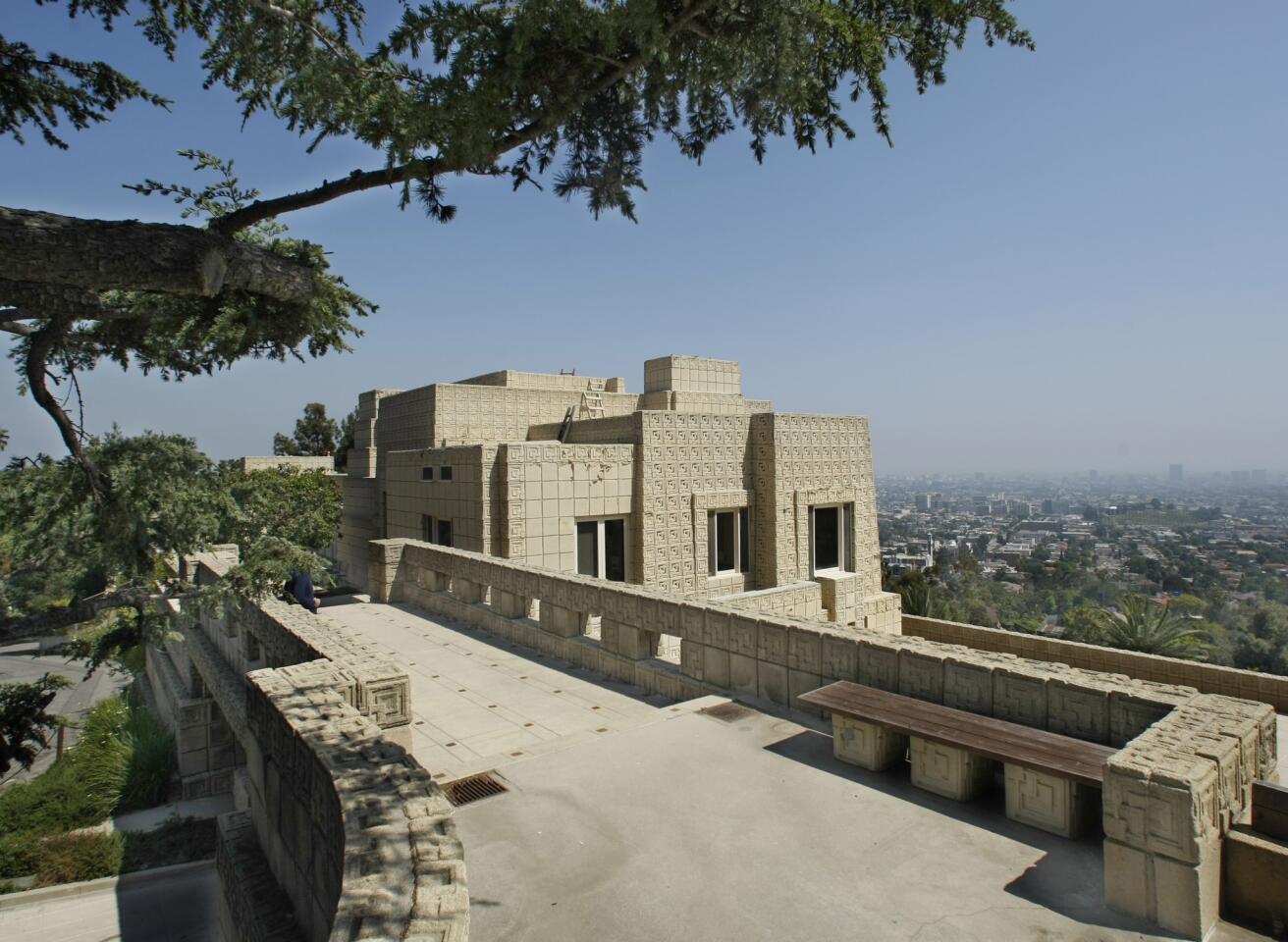

When Frank Lloyd Wright completed the Ennis House in 1924, he immediately considered it his favorite. The last and largest of the four concrete-block houses that Wright built in the Los Angeles area remains arguably the best residential example of Mayan Revival architecture in the country. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Set on nearly an acre in the Los Feliz neighborhood of L.A., the Ennis House cost $300,000 to build in 1924, about $3.8 million today, adjusted for inflation. The main house has three bedrooms and three and half baths; separate staff quarters push the total living space to 6,000 square feet. Note the walkway above the driveway, which we will revisit ... (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

The entry gate and ... (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

… the view from above. Wright’s client was Charles and Mabel Ennis, owners of a men’s clothing store in downtown L.A. and enthusiasts of Mayan art and architecture. Wright created custom patterns for each of his houses built with concrete blocks -- or textile blocks, as they are often called because of the way the patterned squares were knitted together. For the Ennis House, the design was a Greek key, variations of which appear inside and out. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

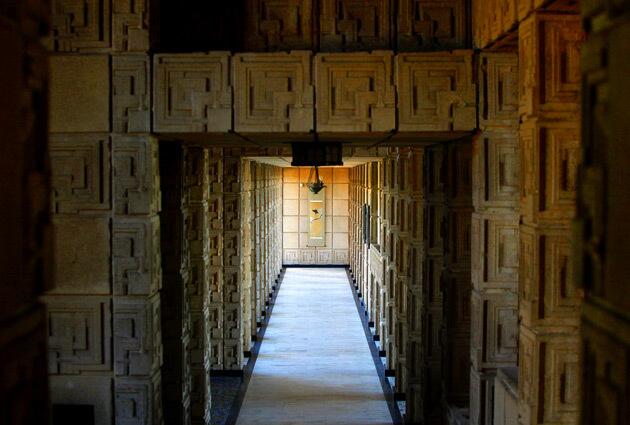

Pictured here: the entry passage. Within some of the concrete blocks, it’s possible to interpret a stylized “g” — perhaps an allusion to the Masonic Order, of which Ennis was a member, and the organization’s symbol, the compass with the letter “g” in the middle representing god. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

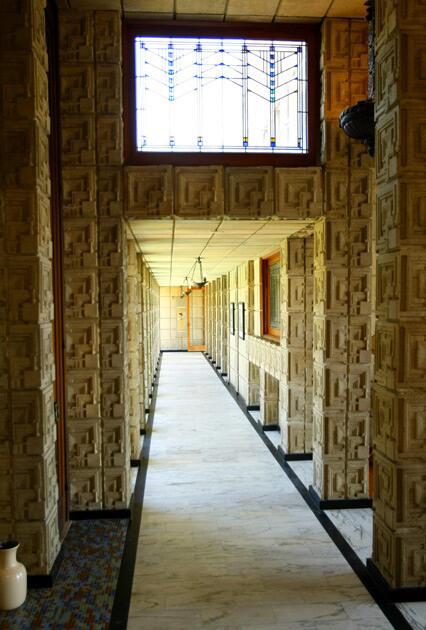

Although the Ennis House was grand in scale and historic in sweep, it remained “highly livable,” said Janet Tani, whose father, Augustus O. Brown, owned the property from 1968 to 1980. Pictured here: a corner of the living room, where the concrete blocks are accented by Wright’s art glass. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

The view from the glass doors, looking back toward Wright’s mosaic fireplace design, right, and marble steps leads up to the dining room, in the distance at left. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

“One gets to experience the changes of light throughout the day and how that impacts interior spaces on a large scale,” former resident Tani said. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Concrete blocks frame an interior view into the dining room. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

The dining room has two areas: a 10-person table for adults, and a smaller table closer to the window for children. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

The house had a series of owners including John Nesbitt, known for his radio and film series “The Passing Parade.” He owned the house from 1940 to 1942. Nesbitt had Wright design a 20-by-40-foot swimming pool and convert a storage area off the entry into a billiard room with a fireplace. These 1940 additions also included Wright’s plans for furniture, window treatments and rugs. In his drawings for Nesbitt, Wright renamed the house Sijistan, after a 10th century Persian palace. Although none of the furniture was built, several chairs were later produced for Wright’s Storer House, another L.A. house built with concrete blocks. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The glass in the house was Wright’s design, and depending of the way the architect controlled the view, you either sensed city life or felt removed into nature, former resident Tani said. “By walking a few feet, one can be in a completely different environment.” (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

The long hallway leads toward the master bedroom. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

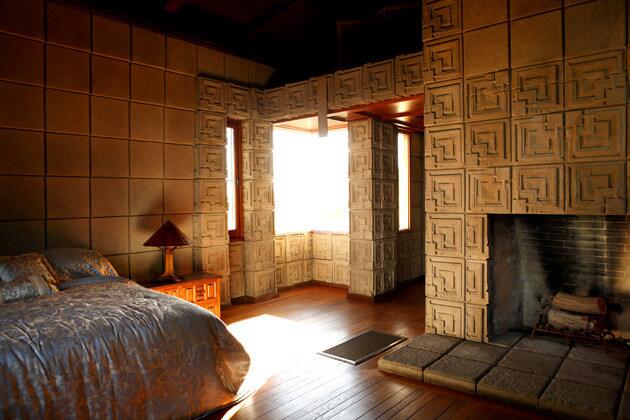

The master bedroom. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Another bedroom view. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Bathrooms have sunken tubs and showers. (Kirk McKoy / Los Angeles Times)

Wright had used concrete in monumental projects before, but in the 1920s it was still considered a new material, especially for home construction. The concrete was a combination of gravel, granite and sand from the site, mixed with water and then hand-cast in aluminum molds to create a block 16 inches wide, 16 inches long and 3.5 inches thick. It took 10 days for each block to dry before it could be stacked into position. The double-wall construction called for exterior blocks and interior blocks to be set about 1 inch apart, and estimates on the total number of blocks deployed by Wright have ranged from 27,000 to 40,000. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

The concrete blocks -- what gave the house its monumental presence -- also have been at the heart of its restoration efforts. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

This 2005 photo shows how rains the year before had damaged the exterior wall, since repaired. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

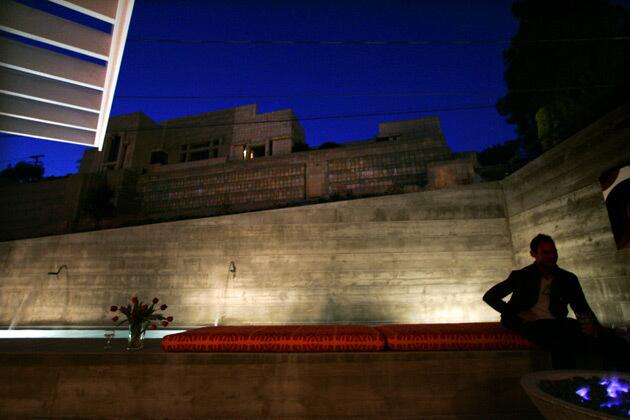

In 2008, The Times’ profiled a new house that architect Barbara Bestor built across the street from Ennis House. In an hommage to Wright, Bestor constructed her streetside privacy wall in a way that showcased her neighbor. Bestor likened it to putting Ennis House on a pedestal, like an objet d’art. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Daunted by the millions needed to finish restoring the house, the Ennis House Foundation put the home up for sale in June 2009, where it has languished despite a price cut from $15 million to $7,495,000. Wright’s grandson, Eric Lloyd Wright, announced the proposed sale by saying a private owner would be better able to preserve the property moving forward. A private owner also would be in keeping with what Wright would have wanted, Eric Lloyd Wright’s statement to the L.A. Times said. “My grandfather designed homes to be occupied by people. His homes are works of art. He created the space, but the spaces becomes a creative force and uplifts when it is lived in every day.”

Full article: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis house

Landmark Houses: Interactive tour of Ray Kappe’s natural wonder (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)